In the nearly 20 years that Megan Stainer worked in nursing homes in and around Detroit, she could almost always tell which patients who were near death received care from non-profit hospices and which from for-profit hospices.

“There were really big differences,” says Ms. Stainer, 45, a licensed practical nurse. Looking at their medical records, “the nonprofit patients always had the most visits: nurses, chaplains, social workers.”

The nonprofit hospices responded quickly when nursing home staff requested supplies and equipment. In contrast, she said, “If you called and said, ‘I need a specialized bed,’ it could take days for profit — days when the patient is in a bed that isn’t comfortable.”

Ms. Stainer, now a private nurse and licensed death doula in Hamburg, Michigan, also found that non-profits were more willing to keep patients enrolled and for-profits were more prone to “live discharge” — removing patients from hospice , ostensibly because they no longer met the declining health criteria, only to re-enroll them later.

“It seemed like people were being fired while they still needed their services,” Ms Stainer said. “There never seemed to be a logical reason.” But long signups and live layoffs could help hospices boost profits and avoid financial penalties, analysts have noted.

Researchers have reported for years that there are indeed substantial differences between for-profit and non-profit hospices; a new study based on the experiences of family caregivers provides additional evidence.

Medicare began covering hospice care four decades ago, when most hospices were nonprofit community organizations that relied heavily on volunteers. It has since become a growth industry dominated by for-profit companies.

In 2001, 1,185 non-profit hospices and only 800 for-profits provided care to Americans with terminal illnesses expected to die within six months. Twenty years later, nearly three-quarters of the country’s more than 5,000 hospices were for-profit, many affiliated with regional or national chains.

The shift was probably inevitable, said Ben Marcantonio, interim director of the National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization, which represents both types, along with some government hospices. About half of the Americans who die each year now go to hospice. The number of Medicare beneficiaries enrolling in hospice increased from 580,000 in 2001 to 1.7 million in 2020.

“The growth of for-profit providers largely meets the growing need,” said Mr. Marcantonio. “It has evolved within a healthcare system that not only accepts but encourages for-profit providers. To think that the hospice would be exempt from that forever was probably unrealistic.’

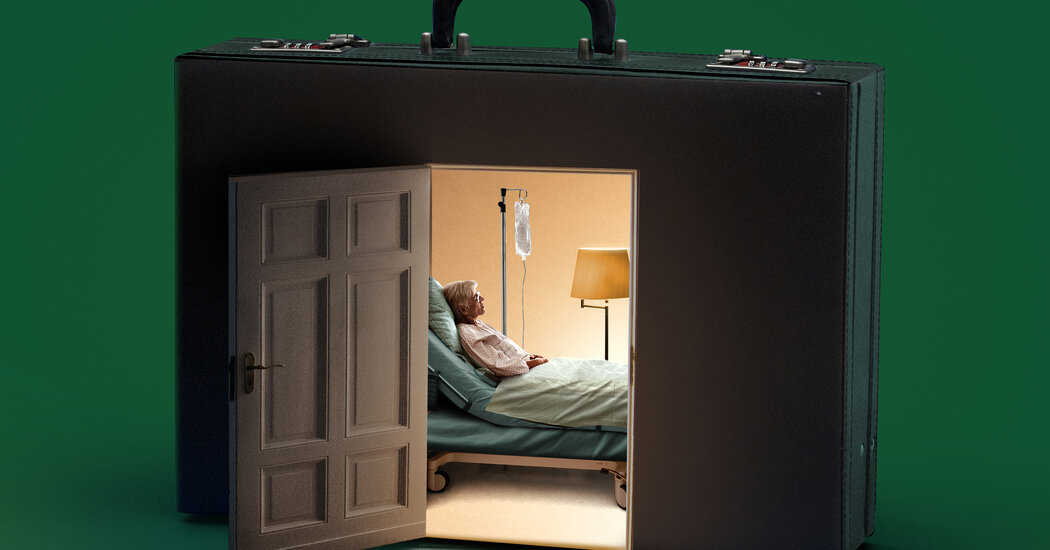

Yet the proliferation of for-profit hospices has fueled fears that dying patients and their families are being shortchanged to improve business outcomes.

The most recent report from MedPAC, the independent agency that advises Congress on Medicare spending, found that in 2020, for-profits received 20.5 percent more from Medicare than they spent on providing services. The margin for nonprofits, whose daily spend per patient is higher, averaged 5.8 percent.

“We’re not getting any profiteering from the company until we make changes,” said Larry Atkins, chief policy officer for the National Partnership for Healthcare and Hospice Innovation, which represents about 100 nonprofit hospices.

He acknowledged, only a little reluctantly, that “there are a lot of advanced players on the profit side doing a decent job.”

Barbara Reiss found that in 2017, as her 85-year-old mother was dying of cancer at her home in River Ridge, La. advice at 2 a.m. The hospice provided all necessary supplies and medicines and sent nurses regularly.

“When we really had problems, they came,” Ms. Reiss said. Her mother died peacefully, and the family turned to the same for-profit hospice three years later, when her father died in assisted living at age 95.

But numerous studies have shown that nonprofits provide better care as a group. All hospices within a geographic area receive the same daily payment per Medicare beneficiary, but patients enrolled in nonprofits receive more visits from nurses, social workers and therapists, according to a 2019 study by the consulting firm Milliman.

For-profit organizations are more likely to discharge patients before they die, a particularly troubling experience for families. “It violates the implicit contract the hospice makes to care for patients until the end of their lives,” said Dr. Atkins.

Dr. Joan Teno, a health policy researcher at Brown University, and her team reported in 2015 on these “awkward transitions,” in which patients were discharged, hospitalized, and then re-admitted to hospice.

That happened to 12 percent of patients in for-profit organizations affiliated with national chains, and 18 percent of patients enrolled in non-chain for-profit organizations — but only 1.4 percent of patients in non-profit hospices.

Dr. Teno’s most recent study, conducted with RAND Corporation, analyzes the family caregiver surveys that Medicare introduced in 2016. Using data from 653,208 respondents from 2017 to 2019, the researchers ranked about 31 percent of for-profit hospices as “underperforming.” well below the national average, compared to 12.5 percent of nonprofits.

More than a third of nonprofits, but only 22 percent of for-profit organizations, performed well. In 2019, the Office of the Inspector General of the Department of Health and Human Services also reported that most of the hospices it identified as underperforming were for-profit.

Aside from such differences, the hospice industry is plagued by fraud in several states. An investigation by The Los Angeles Times in 2020 and by the state auditor found that dozens of new for-profit hospices were certified and billed Medicare in California.

The number far exceeded need, and dozens of hospices shared common addresses, the auditor noted, concluding that “numerous indicators point to widespread hospice fraud and abuse” in Los Angeles County. Last year, the state imposed a moratorium on hospice permits.

In November, national hospice associations urged Medicare to take action in Nevada, Arizona and Texas, where similar patterns of growth and abuse have emerged.

Researchers and critics have also raised the alarm about private equity firms taking over hospice organizations and, with the intention of reselling them within a few years, cut costs through measures such as staff reductions. Most of those acquisitions were previously not-for-profit organizations.

Advocates, researchers and industry leaders have long lists of reforms they believe will fight fraud and improve service, from strengthening the way Medicare conducts quality surveys to moving from a per diem model to more individualized reimbursements.

“Obviously we need to strengthen oversight, but we also need to modernize payment programs to meet patient needs and make it harder for people to play the system,” said Rep. Earl Blumenauer, an Oregon Democrat who has been has long been involved in life-legislation, said in an email.

Meanwhile, families seeking reliable, compassionate hospice care for loved ones should research, at a time when they shouldn’t, to select a provider. “It’s not as simple as avoiding all profit motive,” said Dr. Teno. “Because of the variations, you really have to look at the data.”

The Medicare.gov website lists not only which hospices are non-profit, but also other quality measures. (The National Hospice Locator also provides such information, and the National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization’s CaringInfo site provides general guidance.)

Dr. Teno recommended caution if more than 40 percent of hospice patients have dementia or reside in care homes or nursing homes, both associated with higher profit margins.

High-quality hospices not only provide “routine home care”, the most common type of hospice service, but also a higher level of care when needed, including inpatient services. Look for a hospice with a four- or five-star rating, she added, though some geographic regions don’t have one.

Most caregivers still rate hospice care highly, despite the changes and challenges, but the need for improvement is clear.

“It’s a small segment of the healthcare system, but it’s such an important part,” said Dr. Teno. “If you screw up, people don’t forget.”