William Dale Archerd drank highballs, married often and hated a 9 to 5 job. He was born in Arkansas, slim, with light blue eyes and wavy silver hair. He inspired romantic devotion in women and trust in criminal allies. For decades, his wives and acquaintances were fatally struck by a sudden, convulsive illness that coroners ruled out as a homicide.

His motive was greed, although he never made much money. He was a frail 55 when police finally arrested him at his home in the Alhambra in 1967. “Well, it's been long enough!” he joked. A prosecutor called him “the greatest cold-blooded killer since Bluebeard,” and a judge called him the most evil defendant he had ever seen. There rarely seemed to be a dent in Archerd's composure. Even on death row, he retained his aura of happy insouciance.

Archerd was a born salesman, occasionally marketing vitamins, hearing aids and folding doors. The merchandise he sold best was himself. From 1930 to 1965 he married seven women, sometimes not bothering to divorce the previous one.

He learned his special method of murder – which allowed him to get away with it for so long – as a young hospital attendant. At the Camarillo State Hospital he worked occasionally in the 'insulin shock department' from 1939 to 1941. It was a twenty-bed dormitory for the treatment of schizophrenia in the desperate era before antipsychotic drugs.

As part of the therapy, which has now been discredited, insulin injections would plunge a patient into a deep coma as the brain ran out of sugar.

A pencil was rubbed along the ball of the patient's foot. When the toes flared out in a so-called Babinski response, he “reverted back to the first man, an ape from which we were said to have emerged,” as one of Archerd's former colleagues would testify. This meant that death was close. Glucose woke up patients, sometimes with brain damage that was misinterpreted as psychological improvement.

Because insulin is a natural hormone and injections are quickly absorbed, an overdose was virtually impossible to pinpoint as the cause of death. It was Archerd's choice of poison for at least six victims over 19 years, police said.

His first suspected murder was in 1947. His friend William Jones Jr., a 34-year-old former firefighter, was charged with the statutory rape of a babysitter. It promised to ruin the family's good name. Archerd jumped in to help. The Joneses gave him a few thousand dollars to buy off the babysitter's family. Archerd handed over $300 and kept the rest. He told Jones how to simulate a head injury and avoid the court – an insulin injection would mimic the symptoms. Jones went into a horrible convulsion while Archerd stood quietly at his bedside. “Encephalitis,” said the coroner.

Police believed William Dale Archerd had murdered three of his wives, two men and his 15-year-old nephew. Shown from top left are William Edward Jones Jr., Zella Winders Archerd and Juanita Plum Archerd. Below are Frank Stewart, Burney Kirk Archerd and Mary Brinker Post Archerd. (Jack Carrick/Los Angeles Times)

Nine years later, he called police to the Covina home where he lived with his fourth wife, 48-year-old Zella Winders. He told a ridiculous story: two robbers had broken into the house and injected her with a mysterious substance. The police found two punctures on her buttocks. He refused to let her go to the hospital, and shortly afterwards she was dead, with two additional flat tires. “Bronchopneumonia,” the coroner said.

Two years later he married his fifth wife, 46-year-old Juanita Plum, in Las Vegas. She was dead within days, amid unexplained sweating and convulsions. When her will was read and Archerd found out his take was $1, he dug his fingers into her daughter's shoulders so hard that her knees almost buckled. “An accidental barbiturate overdose,” the coroner said.

In 1960, he convinced a 54-year-old acquaintance, Frank Stewart, to take part in an insurance scam. Insulin is said to mimic the symptoms of a head injury. “Brain hemorrhage,” according to the autopsy.

The following year he pressured his 15-year-old nephew, Burney Kirk Archerd, into a similar plan. They pretended the boy had been hit by a truck, and an insulin injection would mimic the effects. “Bronchopneumonia and cerebral hemorrhage,” the coroner said.

At that point, Los Angeles County sheriff's detectives were convinced Archerd was a serial killer and knew how he did it. To Harold “Whitey” White, a sheriff's lieutenant who recounted the investigation for nearly a decade in his memoir “Whitey's Career Case: The Insulin Murders,” Archerd was “that rotten bastard,” “that slimy bastard” and “that scheming son '. of a bitch.”

“It is an extremely helpless feeling to know that a psychopath like William Dale Archerd can kill so many people, to know how he kills and why, but not be able to come up with a criminal cause of death to prove murder. ,” White wrote.

Archerd murdered his seventh wife, 60-year-old Mary Brinker Post, in November 1966. As a novelist, she had written the bestseller “Annie Jordan,” about a courageous heroine in the booming city of Seattle, modeled on her pioneer family. She suffered horrible convulsions and died at Pomona Valley Hospital. “Hypoglycemic shock due to undetermined,” the autopsy said.

The Sheriff's Department placed White on the investigation full-time. His team wanted to prove a circumstantial case that the murders were united by a common plan and plan. “I decided Archerd's crime spree had gone on long enough. I would get him if it took the rest of my career to do it,” White wrote.

He called in doctors – including leading insulin researchers – to re-examine the medical records of the six known deaths. All deaths, the doctors concluded, were due to an insulin overdose. Brain slides from some victims showed extensive damage that could only have been caused by insulin-induced glucose starvation.

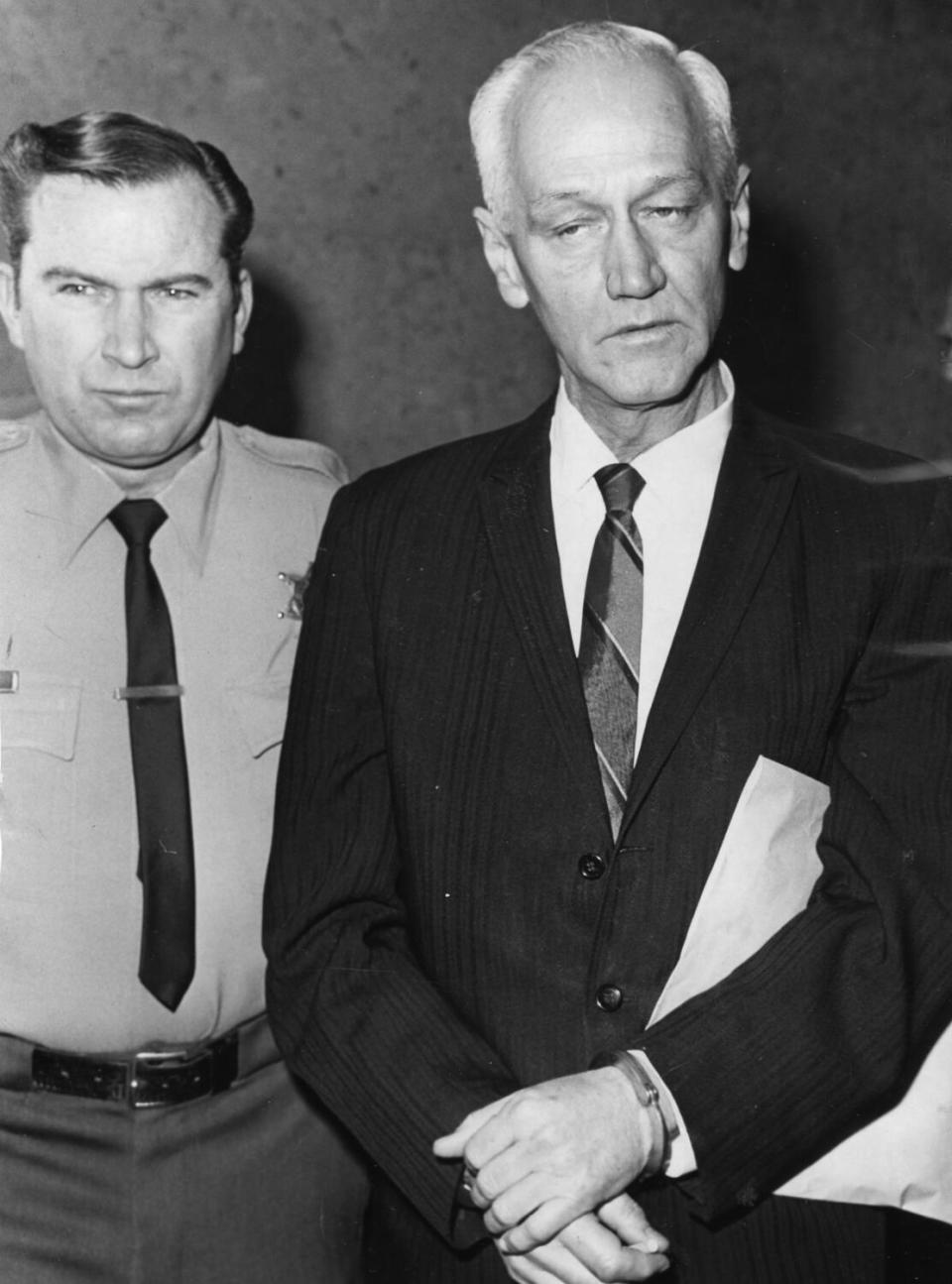

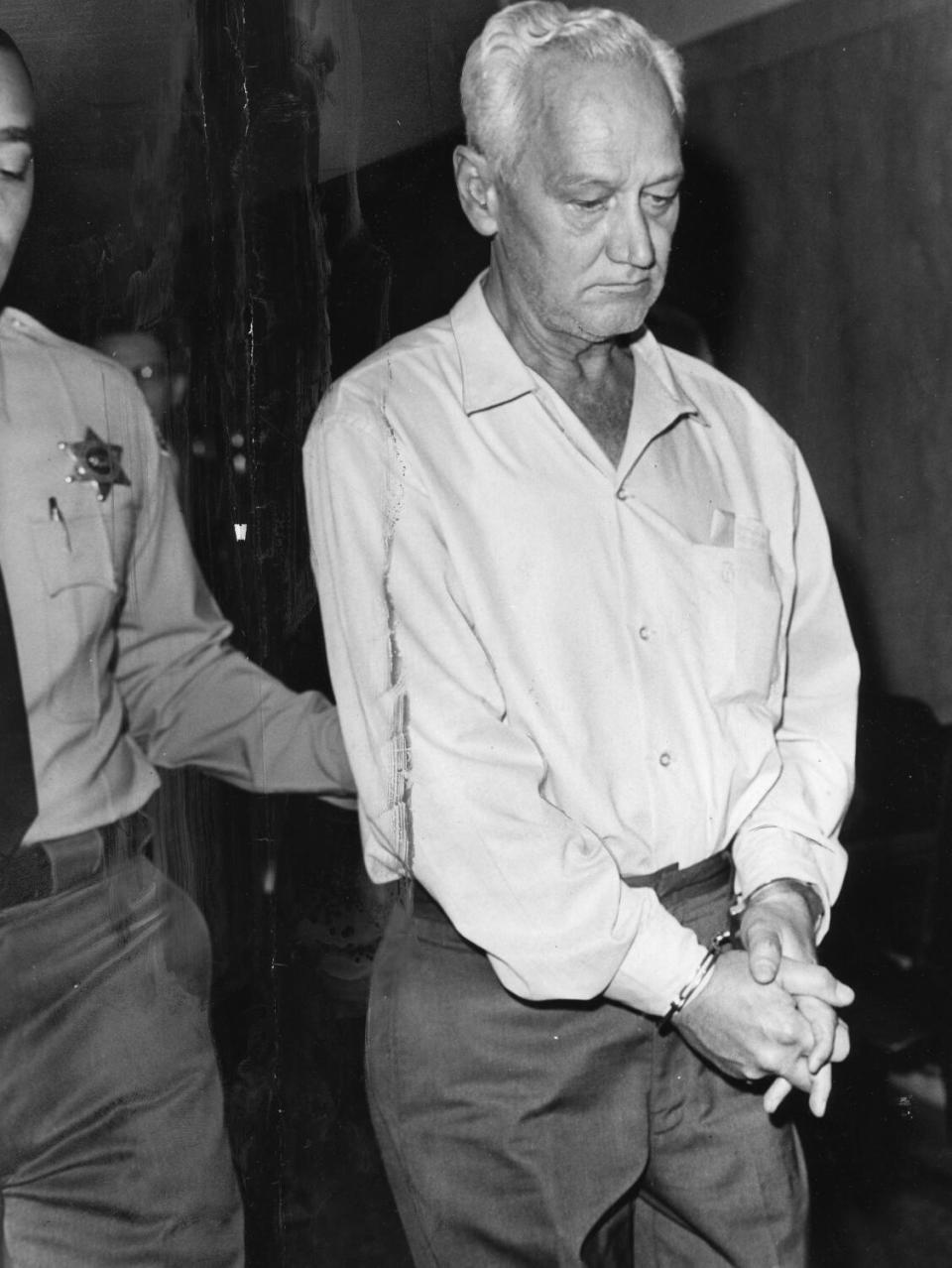

William Dale Archerd, right, comes to court with a bailiff in December 1967. (Bruce Cox/Los Angeles Times)

When White showed up at Archerd's house to arrest him, he found the killer painfully thin, weak and “looking miserable.” Nevertheless, White had to resist the urge to “punch the angry bastard right in the mouth.”

Archerd stood trial for the three LA County deaths — women No. 4 and No. 7 and his cousin — while prosecutors used the other three to establish his decades-long pattern.

The key witness was Archerd's third wife, a former nurse named Dorothea Sheehan, who was furious when he annulled their marriage to marry another woman the next day. She was “a pissed off ex-wife,” White wrote, “and she wanted blood!”

On the stand, she recalled thinking with Archerd about how murder by insulin would make an excellent plot for a mystery story. How he asked her to buy him a bottle of insulin and inject Jones for the insurance scam. How he said that because Jones had raped more than one babysitter, “it was a good thing he died.” And how, when she read about Zella Winders' death in the newspaper, she confronted him about it.

“I said smartly, 'It wouldn't have been insulin, would it?' And he kind of kicked me in the ankle and looked around like he thought maybe my house was bugged.”

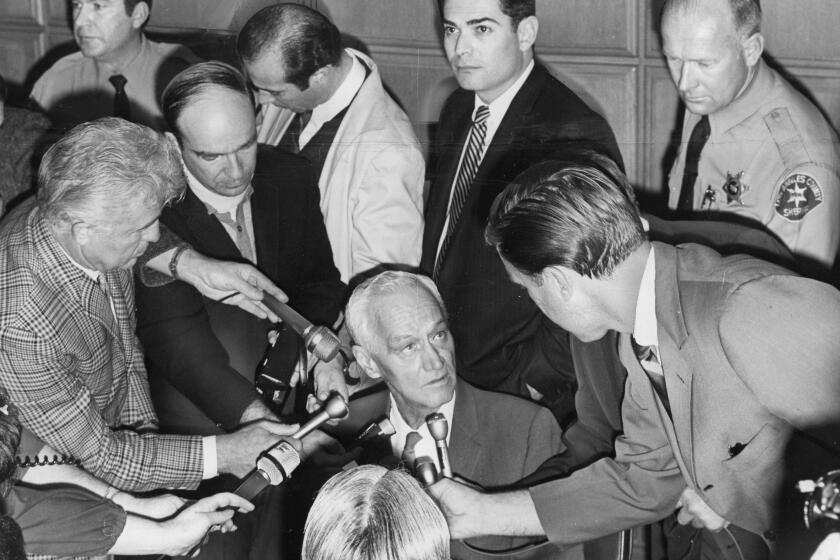

William Dale Archerd is led from the courtroom after his arraignment in July 1967. (Larry Sharkey/Los Angeles Times)

As she recounts in her book “Assassins… Serial Killers… Corrupt Cops…” Mary Neiswender met him while covering his trial for the Long Beach Press-Telegram. He told her stories designed to arouse pity – that as a boy he had dug ditches and required 43 operations for deformed limbs. She decided he was a pathological liar.

“His captors later told me, 'You know, he expected to beat this and was counting on you as his next wife,'” she wrote. “I wasn't flattered.”

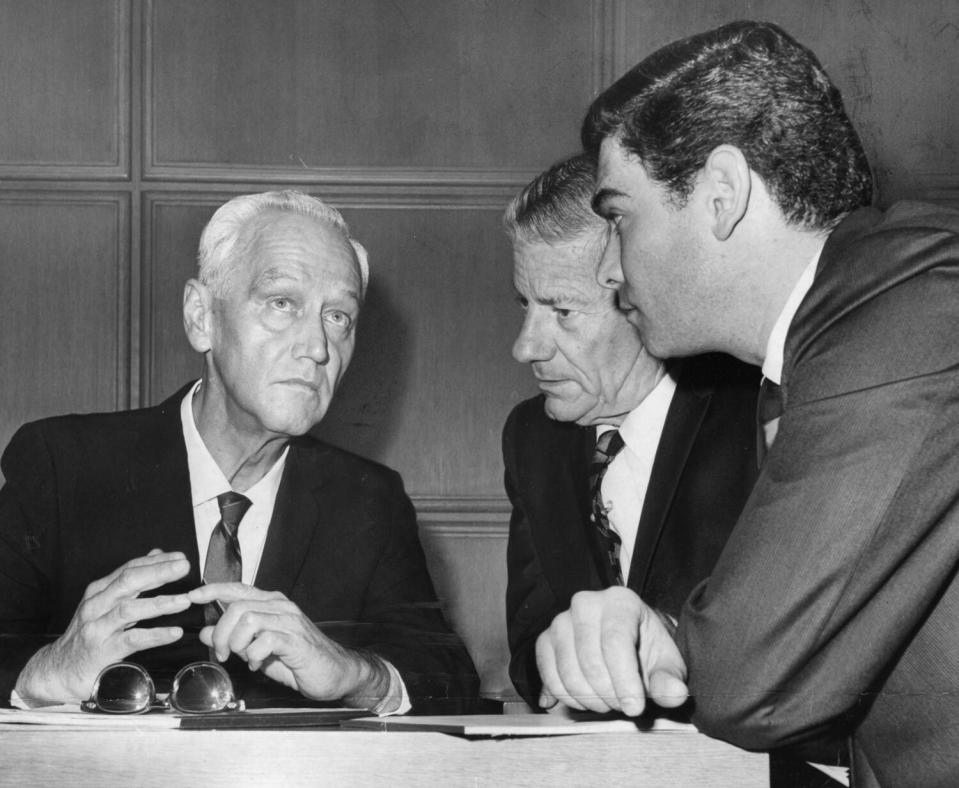

Throughout the two-month trial, Archerd was always relaxed, friendly and respectful with his lawyers. Unlike most defendants in his position, he did not question the decisions of his lawyers. “I don't remember a single time he showed any stress,” Ira Reiner, an attorney representing Archerd, recently told The Times. “Nothing bothered him.”

He chose to have his case heard by a judge instead of a jury because he thought he was less likely to receive the death penalty. Judge Adolph Alexander found him guilty – making him the first convicted insulin killer in the United States – and sent him to death row.

“He thought he had the perfect plan,” said Reiner, 88, who later became LA County district attorney. “If there had been one case indicted and one case only, there was certainly a reasonable possibility that a judge or jury would have been acquitted. The problems followed one another.”

When Archerd's death warrant was signed, Reiner won a last-minute stay. He went to San Quentin to deliver the order personally, rather than risk sending a fax that arrived too late. He remembers Archerd's nonchalance when he heard the good news.

“It's hard to describe how completely relaxed he was,” Reiner said. However, Archerd was outraged that prison officials had offered him a final meal of steak or lobster, but not both.

“He said, 'They're going to kill me, and they want to argue with me about whether I can eat steak and lobster.' He said, 'It's not fair, it's not right.' Like he was arguing with a waiter.”

Archerd's death sentence was eventually commuted to life in prison, and he died of natural causes in 1977 at the age of 65. He was “a charming sociopath,” Reiner said. “You can't kill so many people and be so relaxed and charming unless there's a little piece missing.”

William Dale Archerd, left, confers with his attorneys Philip Erbsen, center, and Ira Reiner in court in February 1968. (Jack Carrick/Los Angeles Times)

Sign up for Essential California to get news, features, recommendations from the LA Times and more delivered to your inbox six days a week.

This story originally appeared in the Los Angeles Times.