In space you don’t hear a black hole screaming, but apparently you do hear it singing.

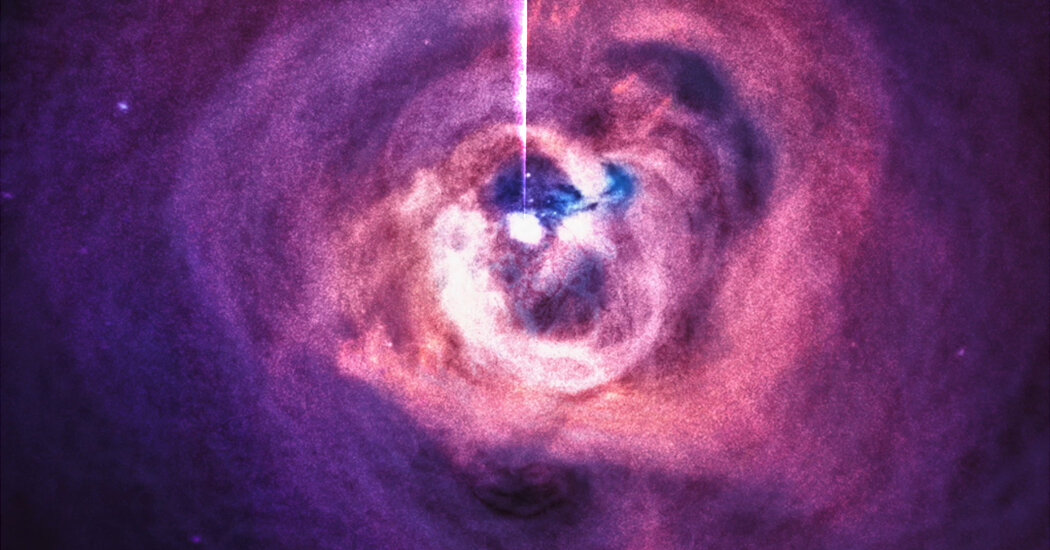

In 2003, astrophysicists working with NASA’s orbiting Chandra X-ray Observatory discovered a pattern of ripples in the X-ray glow of a giant cluster of galaxies in the constellation Perseus. They were pressure waves — that is, sound waves — 30,000 light-years in diameter that radiated outward through the thin, ultra-hot gas engulfing galaxy clusters. They were caused by periodic explosions from a supermassive black hole at the center of the cluster, 250 million light-years away and containing thousands of galaxies.

With an oscillating period of 10 million years, the sound waves were acoustically equivalent to a B-flat 57 octaves below middle C, a tone the black hole has apparently held for the past two billion years. Astronomers suspect that these waves act as a brake on star formation, leaving the gas in the cluster too hot to condense into new stars.

Chandra’s astronomers recently “sonicated” these ripples by accelerating the signals to 57 or 58 octaves above their original pitch, raising their frequency quadrillions of times to make them audible to the human ear. As a result, the rest of us can now hear the intergalactic sirens singing.

Through these new cosmic headphones, Perseus’ black hole makes an eerie groan and rumble that reminded this listener of the reverberating tones marking an alien radio signal that Jodie Foster hears through headphones in the science fiction film “Contact.”

As part of an ongoing project to “sonify” the universe, NASA has also released similarly generated sounds from the bright nodes in an energy beam shooting from a giant black hole at the center of the giant galaxy known as M87. These sounds reach us about 53.5 million light-years away as a stately succession of orchestral tones.

Yet another sonication project has been undertaken by a group led by Erin Kara, an astrophysicist at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, as part of an effort to use light echoes from X-ray bursts to map the environment around black holes, much like bats use. sound to catch mosquitoes.

All of this is an outgrowth of “Black Hole Week,” an annual NASA social media extravaganza, May 2-6. This week is a prelude to big news on May 12, when researchers with the Event Horizon Telescope, which produced the first image of a black hole in 2019, announce their latest results.

Black holes, as defined by Einstein’s general theory of relativity, are objects with a gravitational pull so strong that nothing, not even light, let alone sound, can escape. Paradoxically, they can also be the brightest things in the universe. Before any form of matter disappears into a black hole forever, theorists suspect, it would be accelerated to near speeds of light by the hole’s gravitational field and heated, swirling, to millions of degrees. This would cause X-ray flashes, generate interstellar shock waves and force high-energy rays and particles through space like toothpaste from a tube.

In a common scenario, a black hole in a binary system containing a star exists and steals material from it, which coalesces into a dense, bright disk – a visible doom donut – that produces sporadic X-ray bursts.

Using data from a NASA instrument called the Neutron Star Interior Composition Explorer – NICER – a group led by Jingyi Wang, an MIT graduate student, looked for echoes or reflections of these X-rays. The time lag between the original X-rays and their echoes and distortions caused by their proximity to the strange gravitational pull of black holes provided insight into the evolution of these violent outbursts.

Meanwhile, Dr. Kara collaborated with education and music experts to convert the X-ray reflections into audible sound. In some simulations of this process, she said, the flashes go all the way around the black hole, causing a telltale shift in their wavelengths before being bounced off.

“I just love that we can ‘hear’ general relativity in these simulations,” said Dr. Kara in an email.

Eat your heart out, Pink Floyd.