University of Waterloo scientists have identified one of the doomed crew members of Captain Sir John S. Franklin's 1846 Arctic expedition to cross the Northwest Passage. According to a recent article published in the Journal of Archaeological Science, DNA analysis revealed that a tooth recovered from a lower jaw at one of the relevant archaeological sites was that of Captain James Fitzjames of HMS. Erebus. His remains show clear signs of cannibalism, confirming early reports from the Inuit that desperate crew members were eating their dead.

“Concrete evidence of James Fitzjames as the first identified victim of cannibalism lifts the veil of anonymity that for 170 years has shielded the families of individual members of the 1845 Franklin Expedition from the gruesome reality of what happened to their ancestor's body could have happened.” authors wrote in their article. “But it also shows that neither rank nor status was the guiding principle in the expedition's last desperate days as they strove to save themselves.”

As previously reported, Franklin's two ships, HMS Erebus and the HMS Terrorbecame frozen in the Victoria Strait and eventually all 129 crew members died. It is an enduring mystery that has captured the imagination ever since. Novelist Dan Simmons immortalized the expedition in his 2007 horror novel, The terrorwhich was later adapted into an anthology TV series for AMC in 2018.

The expedition departed on May 19, 1845 and was last seen in July 1845 in Baffin Bay by the captains of two whaling ships. Historians have put together a fairly credible account of what happened. The crew spent the winter of 1845-1846 on Beechey Island, where the graves of three crew members were found.

When the weather cleared, the expedition sailed into Victoria Strait before becoming trapped in the ice off King William Island in September 1846. Franklin died on June 11, 1847, according to a surviving note signed by Fitzjames from the following April. Fitzjames had assumed overall command after Franklin's death and led 105 survivors from their ice-trapped ships. It is believed that all the others died while camped for the winter or while trying to walk back to civilization.

There was no concrete news about the fate of the expedition until 1854, when local Inuits told 19th-century Scottish explorer John Rae that they had seen about 40 people dragging a ship's boat on a sled along the south coast. The following year, several bodies were found near the mouth of the Back River. A second search in 1859 led to the discovery of a site some 50 miles south of that spot called Erebus Bay, as well as several more bodies and one of the ship's boats still mounted on a sled. In 1861, another site with even more bodies was found just two kilometers away. When these two sites were rediscovered in the 1990s, archaeologists named them NgLj-3 and NgLj-2, respectively.

The authors of this latest article have been conducting DNA research for several years to identify the remains found at these sites by comparing DNA profiles of the remains with samples taken from descendants of the expedition members. To date, 46 archaeological samples (bones, teeth or hair) from Franklin Expedition-related sites on King William Island have been genetically profiled and compared to cheek swabs from 25 descendants. Most did not match, but in 2021 they identified one of those bodies as chief engineer John Gregory, who worked on the Erebus. Since then, the team has added four more descendants: one related to Fitzjames (technically a second cousin five times removed through the captain's great-grandfather).

A plea for cannibalism

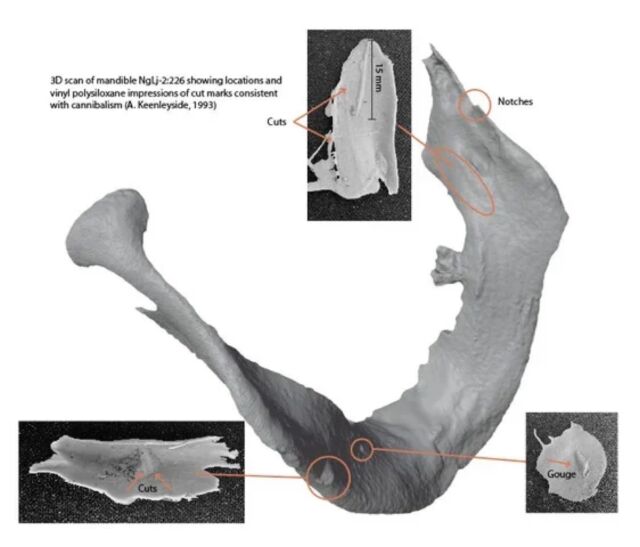

In the 1850s, the Inuit had reported evidence that the survivors were resorting to cannibalism, but these stories were dismissed by the Europeans, who found such a practice too shocking and depraved to be credible. But in 1997, the late bioarchaeologist Anne Keenleyside of Trent University identified lacerations on almost a quarter of the human bones at NgLj-2, concluding that at least four of the men who died there had been cannibalized.

This new study is the result of DNA testing on 17 tooth and bone samples from the NgLj-2 site, first recovered in 1993. The samples included a tooth from a mandible, which became the second sample to yield a positive identification . “We were working with a good quality sample that allowed us to generate a Y chromosome profile, and we were fortunate to obtain a match,” says co-author Stephen Fratpietro of the Paleo-DNA Laboratory at Lakehead University in Ontario. The authors believe that Fitzjames probably died in May or June 1848.

The Fitzjames mandible is also one of the bones that shows multiple cut marks. “This shows that he preceded at least some of the other sailors who died, and that neither rank nor status was the guiding principle in the final desperate days of the expedition as they strove to save themselves,” says co- author Douglas Stenton, one of the researchers. anthropologist at the University of Waterloo.

'The most sympathetic response to the information presented here is to use it to recognize the degree of desperation that Franklin's sailors must have felt for doing something they would have found abhorrent, and to acknowledge the sadness of the fact that in this case, doing so only prolonged their suffering,” the authors concluded.

Journal of Archaeological Science, 2024. DOI: 10.1016/j.jasrep.2024.104748 (About DOIs).