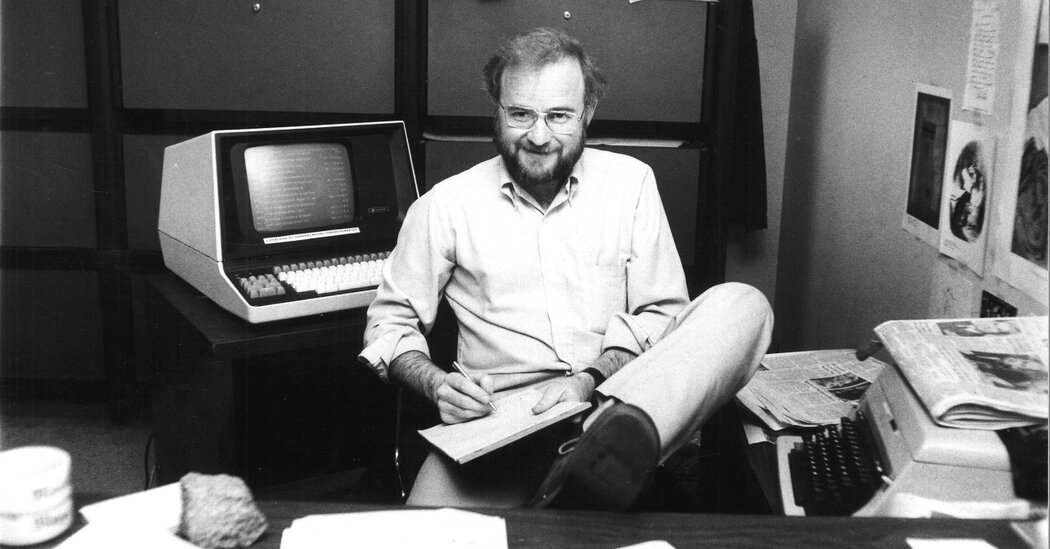

Francis X. Clines, a reporter, columnist and foreign correspondent for The New York Times whose news commentary and lyrical profiles of ordinary New Yorkers were widely admired as a stylish, literary form of journalism, died Sunday at his Manhattan home. He was 84.

His wife, Alison Mitchell, a senior editor and former assistant editor at The Times, said the cause was esophageal cancer, which was diagnosed in February 2021.

For generations of Times colleagues, Mr. Clines was a near-ideal reporter: a keen observer, a tenacious fact-seeker, and a model of integrity and honesty who could write gracefully against a deadline. He withstood praise with a shrug or a little self-mockery.

He worked his entire 59-year career for The Times (1958-2017), starting as a copyboy with no college degree or formal journalism training. After years as a political reporter at New York City Hall, the Albany Statehouse and the Reagan White House, he corresponded from London, the Middle East, Northern Ireland and Moscow, covering the final days of the Soviet Union. Union.

Later, as a national correspondent, he followed political campaigns and the Washington scene, making occasional forays into the hills and hollows of the Appalachian Mountains to write about a largely hidden Other America. And nearly two decades before retiring, he produced editorials and columns with “Editorial Observer” greeting the workers and social progressives and criticizing the gun lobby and Donald J. Trump.

Mr. Clines established his reputation as a literary stylist with “About New York,” a long-running column started by Pulitzer Prize-winning reporter Meyer (Mike) Berger, who died in 1959. One of Berger’s many successors, Mr. Clines wrote the column from 1976 to 1979. Though occasional about news-related events, his column was mainly devoted to vivid portraits of New Yorkers – the rich and the poor, the influential and the forgotten. .

He called them sketches of the city. They were factual profiles of his observations and literary allusions, often humanistic in tone and very personal, like a brother’s letters home about extraordinary people he had met.

“Tomorrow is Alice Matthew’s birthday,” wrote Mr. Clines in typical fashion on October 6, 1976, “and if you ask politely, she will tell you about her 93 years, from the moment she saw the spotted firehorse that led to her.” elopement from Indiana, 74 years ago, to the night here in her welfare chamber where she saw the ghost of Louis XIV, and he let his beautiful white horse lay his head on the bedridden woman’s blanket to comfort her.”

“None of these stories are sad,” he continued. “Mrs. Matthews takes care of that. She represents a small drain on the city’s Human Resources Administration budget. But she herself is an important human source of memory and good company, which logically belongs in the slick Big Apple ads about the strengths of the city as in the roach-infested room she graces at the Hotel Earle near Washington Square.

Mr. Clines wrote three 900-word columns about New York each week. He profiled a lone Etruscan scholar who pursued his work from a single room in a “thrifty hotel on the West Side,” and a shoe salesman who turned pages for concert pianists. He went to a racecourse with a wealthy landlord, spent a night watching streetwalkers, and sometimes only listened to nighttime noises after hours at the Bronx Zoo. Once he attended a Chinese funeral with an Italian band playing the lament.

“Besides a matter of life and death, the tableau represented a bit of symbiosis in neighboring cultures of Chinatown and Little Italy that thrive around Canal Street in Manhattan,” he wrote. “So there was Carmine in Bacigalupo’s who gathered his men in front of Mr. Yee’s open casket and gave a downbeat to songs like ‘What a Friend We Have in Jesus’ and a soft, light-hearted tune from the old neighborhood, ‘Il Tuo Popolo’ (“Your people”) The music seemed to calm the mourners.”

On a night of marauding crowds during a citywide power outage in 1977, Mr. Clines an uglier side of town: “The looters scattered, like cockroaches, in the full morning sunlight, then stopped to look cheeky when the owner of Joe’s candy store saw his shop broken into on the doorstep of Brownsville. He let out a furious howl. .”

The columns of Mr. Clines won Columbia University’s Mike Berger Award in 1979, and the following year the best of them were collected in a book, “About New York.”

A London correspondent from 1986 to 1989, he covered British politics, art and general news, as well as traveling breaking news in the mainland, the Middle East and Northern Ireland, where gunfights and terrorist bombings are known. standing as “the Troubles” killed Protestants and Catholics with narcotic regularity.

He followed up that broadcast with one in Moscow from 1989 to 1992, when he helped cover the end of Mikhail S. Gorbachev’s presidency and the collapse of Soviet communism.

But from wherever he wrote, he brought the same attentive eye and finely tuned ear to his reporting. For example, in 1988 from Belfast he wrote about a little girl surrounded by death:

“Behind the coffin, in the graveyard, redhead Kathleen Quinn had been flirting with pleasure and shameless for eight years. “Sir, I have to be on TV tonight,” she said to a stranger, squeezing happy and prim. Kathleen had grabbed her brother’s bike and bloodied her knee as people in church said goodbye to another rebel body in another coffin.

“It turned out that television was ignoring Kathleen and missing a classic Irish truth, pleasing to the eye. She climbed back on the bike and rode off in a haze, oblivious to a patch of graffiti nearby that seemed all about the destructive dangers of life: “I wonder every night what the monster will do to me tomorrow. ‘”

Francis Xavier Clines was born in Brooklyn on February 7, 1938, the youngest of three children of an accountant, Francis A. Clines, and Mary Ellen (Lenihan) Clines. The boy, named Frank, and his sisters, Eileen and Peggy, grew up in the Bay Ridge neighborhood of Brooklyn.

Frank attended St. Francis Preparatory School for Boys and then Williamsburg Section, graduating first in his class in 1956. He was a fan of Brooklyn Dodgers and an avid reader of novels, biographies, history and poetry. He enrolled at Fordham University but soon dropped out before serving in the military for two years.

After his discharge, he applied for a job at The Times and was hired largely on the basis of an essay he submitted outlining his hopes for a journalistic career. After a year of administrative work, he wrote radio news bulletins for WQXR, The Times’ AM and FM stations, and covered police actions and general assignments.

His marriage to Kathleen Conniff in 1960 ended in divorce in the early 1990s. He married Ms. Mitchell, when she was the City Hall headquarters for The Times, and the two met when she was the Moscow bureau chief for Newsday.

In addition to Mrs. Mitchell, he leaves behind his first wife; four children from his first marriage, John, Kevin, Michael and Laura Clines; and a sister, Eileen Lawrence. Another sister† Peggy Meehan Simon, passed away.

There are many ways to reduce pomposity, which is one of the reasons Mr. Clines liked to deal with the state legislature in Albany. Beyond the thump of new laws and proposed taxes, he dissected the mores of less-familiar lawmakers with a Celtic sense of the absurd: their exaggerated rhetoric about public service, their crude eating habits during debates, their losing bouts with the native tongue—all were honest. game and duly reported.

“I think he was the greatest newspaper writer of our time,” Charles Kaiser, a former Times reporter, said in a recent email. “Its success said more about the newspaper’s dedication to beautiful writing than anything else could.”

Mr Clines once wrote a column on Seamus Heaney, the Irish poet, which was perhaps a sort of self-disclosure, saying: “He fights to keep things basic, to remind himself of the simple wisdom of Finn MacCool, the mythical national hero, that the best music in the world is the music of what happens.In his “Elegy,” dedicated to Lowell, Heaney reminded himself:

‘The way we live,

Timorous or daring,

Must have been our life.’”