The US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention today released an update on the monkeypox situation in the US, which is linked to a growing multinational outbreak. It also used the time to answer open-ended questions and calm some unfounded fears.

To date, there are five confirmed and probable cases in the US. The only confirmed case of monkeypox in the US was diagnosed last week in a Massachusetts man who had recently traveled to Canada. The four likely cases include one in New York City, one in Florida and two in Utah.

Those four cases are likely because they all tested positive for an orthopoxvirus, the family of viruses that includes monkeypox and smallpox. They are considered suspected cases of monkeypox and are treated as such, while the CDC conducts secondary testing to confirm monkeypox.

All five confirmed and probable cases in the US are male and all have histories of international travel befitting the multinational outbreak.

The CDC also used today’s briefing to emphasize that it sequenced the monkeypox virus genome from the first case in Massachusetts. The genetic sequence closely matches that of a case in Portugal.

Worldwide, there are nearly 250 confirmed and suspected cases from 17 countries, most of them in Europe. About 165 cases have been confirmed and 83 are suspected (you can follow the growing number here and here). The cases are mainly in men and especially in men who identify as gay, bisexual or are men who have sex with men (MSM).

This is an unusual outbreak that requires immediate attention and swift action, according to health officials worldwide. However, the risk to the general population is still considered low.

“This is not an easily transmissible virus via respiratory droplets and things like that,” said Capt. Jennifer McQuiston, deputy director of the CDC’s Division of High Consequence, in today’s briefing.

“This is not COVID,” she added. “We know a lot about monkeypox from many decades of research, and respiratory spread is not the main concern. It’s contact – and intimate contact – in the current outbreak and population. And that’s really what we wanted to emphasize.”

Below is a brief overview of critical questions and answers:

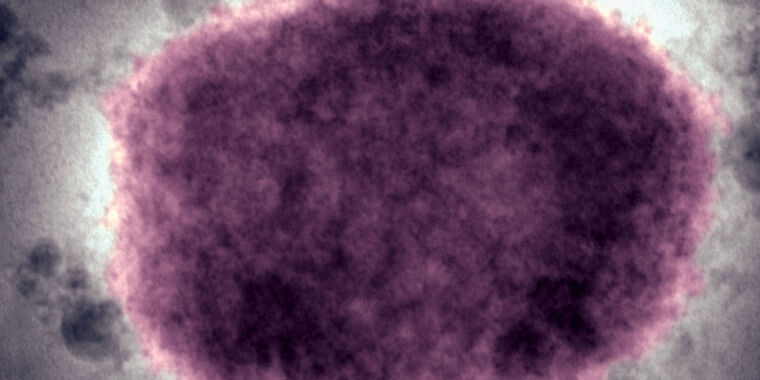

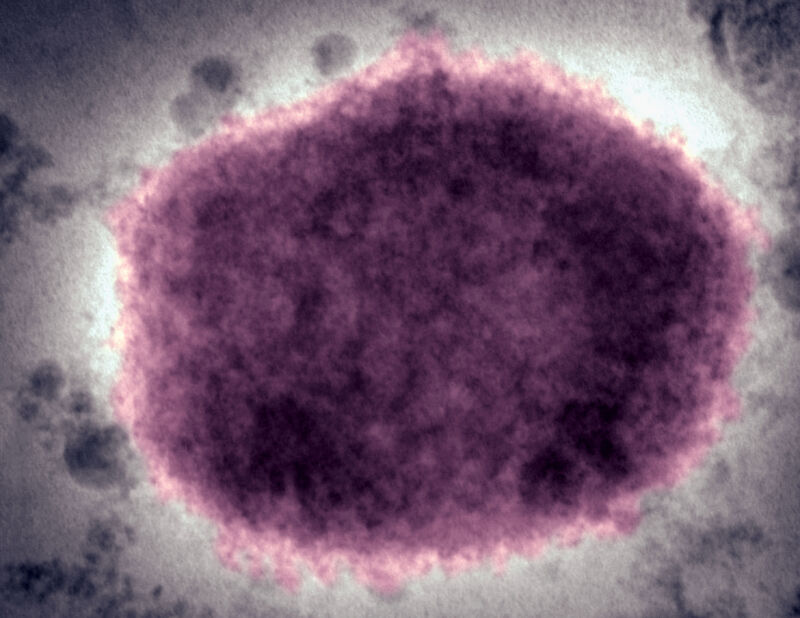

What is monkeypox virus?

Monkeypox is a DNA virus related to smallpox that infects animals and is endemic to forested areas of Central and West Africa. It is unclear which animal or animals act as a reservoir for monkey pox, but rodents are the prime suspects. The virus can also infect rats, squirrels, prairie dogs, several monkey species and other animals.

It got its name when researchers first discovered the virus in monkeys in a Danish lab in 1958, according to the World Health Organization. The first human case was diagnosed in 1970 in a child in the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

It is largely believed that humans become infected through hunting and handling of wild animals and bushmeat.

There are two clades of monkeypox: the West African clade and the Congo Basin clade. The West African clade is the milder of the two, with an estimated human mortality rate of about 1 percent. The Congo Basin clade has an estimated death rate of up to 10 percent.

Which clade is causing the current outbreak?

The West African clade, the milder.

What are the symptoms?

Once infected, a person usually develops symptoms five to 13 days after exposure, but the incubation period can range from five to 21 days.

Monkeypox usually begins with fever and flu-like symptoms, especially headache, fatigue, muscle aches and swollen lymph nodes. One to three days later, skin lesions develop all over the body (a telltale rash), but tend to focus on the face and extremities, especially the palms and soles. The lesions start flat at the base and then become elevated and filled with fluid. A crusty scab then forms over each lesion and later falls off. The number of lesions an infected person develops can range from a few to several thousand, according to the WHO.

The disease generally lasts two to four weeks and resolves without specific treatments.