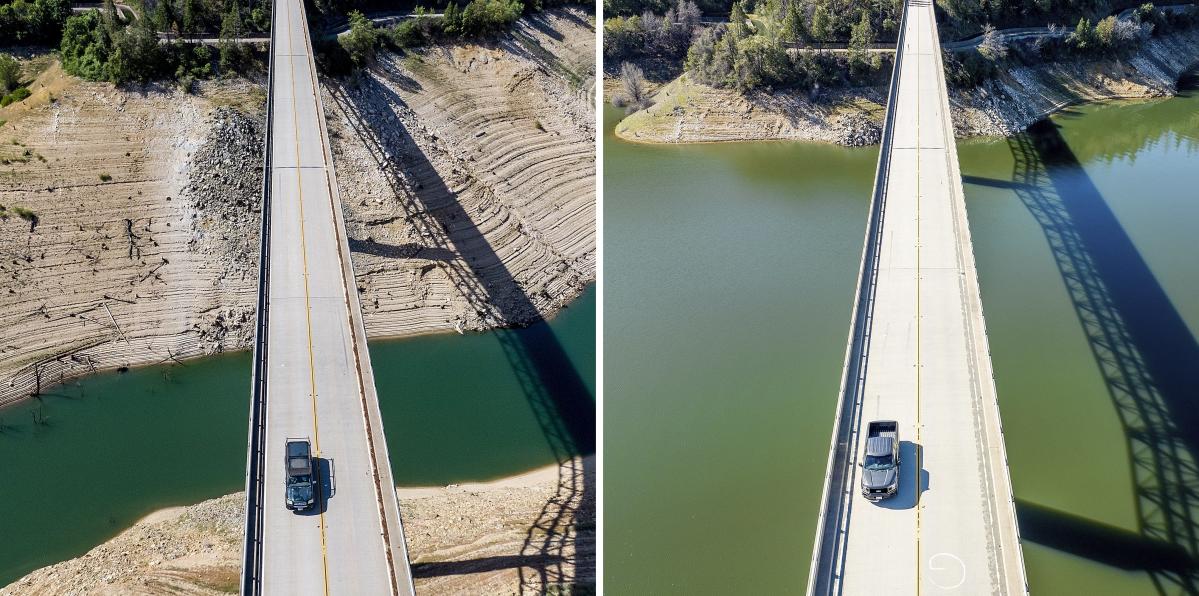

FOLSOM, Calif. (AP) — During the depths of California’s drought, water levels in key reservoirs dropped so low that jetties sat on dry, cracked land and cars drove into the center of what should have been Folsom Lake.

Those scenes are gone after a series of powerful storms dumped record amounts of rain and snow in California, replenished reservoirs and ended — largely — the state’s three-year drought.

Now 12 of California’s 17 major reservoirs have filled above their historical averages before the onset of spring. That includes Folsom Lake, which regulates water flows along the American River, as well as Lake Oroville, the state’s second-largest reservoir and home to the nation’s tallest dam.

It’s a stunning turnaround in water availability in the country’s most populous state. At the end of last year, almost all of California was in drought, including at extreme and exceptional levels. Wells dried up, farmers broke fields, and cities limited grass watering.

The water picture changed dramatically from December, when the first of a dozen “atmospheric rivers” hit, causing widespread flooding and damage to homes and infrastructure, and sending as much as 700 inches (17.8 meters) of snow into the Sierra Nevada mountains. dumped.

“California went from three driest years on record to three wettest weeks on record when we were catapulted into our rainy season in January,” said Karla Nemeth, director of the California Department of Water Resources. “So, hydrologically speaking, California is no longer in a drought, except in very small parts of the state.”

All the rain and snow, while fighting the drought, can bring new challenges. Some reservoirs are so full that water is being discharged to make way for storm runoff and melting snow that could cause flooding this spring and summer, a new problem for weary water managers and emergency responders.

The storms have created one of the largest snowpacks ever recorded in the Sierra Nevada mountains. The snowpack’s water content is 239% of the normal average and nearly three times that of the southern Sierra, according to state data. As the weather warms, water managers are preparing for all that snow to melt, creating a deluge of water expected to cause flooding in the foothills of the Sierra and Central Valley.

“We know there will be flooding as a result of the snowmelt,” Nemeth said. “There’s just too much melting snow to be collected in our rivers and canals and keep things between levees.”

Managers are now discharging water from the Oroville Dam spillway, which was rebuilt after it broke apart during heavy rains in February 2017, forcing the evacuation of more than 180,000 people downstream along the Feather River.

The reservoir is 16% above the historical average. That is compared to 2021, when the water level dropped so low that the hydroelectric dams no longer generated power.

That year, the Bidwell Canyon and Lime Saddle marinas had to pull most of their recreational boats out of Lake Oroville and shut down their boat rental business because the water level was too low and it was too difficult to get to the marinas, said Jared Rael, who manages the marinas.

In late March, the water at Lake Oroville rose to 859 feet (262 meters) above sea level, about 230 feet (70 meters) higher than its 2021 low, according to state data.

“The public will benefit from the higher water. Everything is easier to reach. They can just jump on the lake and have fun,” Rael said. “Right now we have tons of water. We have a high lake with a lot of snow. We’re going to have a great year.”

The abundant rainfall has prompted Governor Gavin Newsom to lift some of the state’s water restrictions and stop asking people to voluntarily reduce their water consumption by 15%.

Newsom has yet to declare the drought over because water shortages continue along the California-Oregon border and parts of Southern California that depend on the struggling Colorado River.

Cities and irrigation districts that provide water to farms will receive a major boost in water supply from the State Water Project and Central Valley Project, networks of reservoirs and canals that provide water throughout California. Some farmers use the rainwater to replenish underground aquifers that had been depleted after years of pumping and drought that left wells dry.

State officials are warning residents not to fall back on wasting water due to the current abundance. In the era of climate change, an extremely wet year can be followed by several dry years, making the state dry again.

“Given the weather conditions, we know the return of dry conditions and the intensity of the dry conditions that are likely to return means we need to use water more efficiently,” Nemeth said. “We need to adopt conservation as a way of life.”

___

Berger reported from Oroville, California.