Dickson Despommier, a microbiologist who suggested that cities should grow food in high-rise buildings and make the term 'vertical agriculture' popular-an idea that crossed the empire of purely imaginative to be a reality all over the world on February 7 on February 7. In Manhattan. He was 84.

His wife, Marlene Bloom, confirmed death in a hospital. He lived in Fort Lee, NJ

Dr. Despommier (pronounced as de-Pom-Ee-Yay), who was a professor for 38 years at the Columbia's School of Public Health, specialized in parasitic diseases, but he got much broader influence as a guru of vertical agriculture.

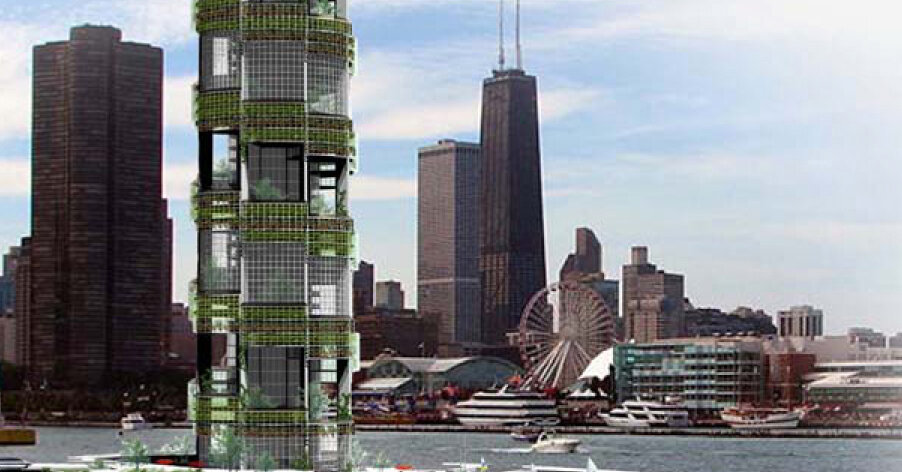

In 2001 he and students in a medical ecology class designed a 30-storey building that could grow theoretical food for 50,000 people. About 100 types of fruit and vegetables would be grown on the upper floors, with chickens that are housed at the bottom down. Fish would feed on plant waste.

Dr. Despommier argued that vertical farms would use 70 to 90 percent less water than traditional farms, so that agricultural land could return to a natural state and help climate change. He evangelized during TEDx conversations and in a book: “The Vertical Farm: Feeding the world in the 21st century.”

“When my book came out, in 2010, there were no functioning vertical farms that I was aware of,” he told the New Yorker a few years later. “By the time I published a revised edition in 2011, vertical farms were built in England, Holland, Japan and Korea.”

Technical investors gutters money in vertical agriculture. The operations generally replaced within LED lights for sunlight and used water systems that plant roots have jumped – no soil required. The farms sprout in places as varied as the center of Newark and Dubai, on the Persian Gulf.

The Guardian estimated that in 2022 there were more than 2,000 vertical farms in the US, so that fruit and vegetables were raised in stacked drawers or long columns, some multiple stories high, some by robots. That year, Walmart announced that the salad groins would harvest a vertical farm in Compton, California, to be run by a company called PLY.

More recently, the industry has come across. High interest rates and energy costs have led to many activities closing or declare bankruptcy. They include it in Compton and that in Newark, Aerofarms, who in his article about Dr. Despommier was prominent in 2017. A company with farms in three eastern states, Bowery Farming, whose investors Justin Timberlake and Natalie Portman and which was once appreciated at $ 2.3 billion, ended last year.

Critics wondered if the vertical agriculture really lowers the carbon emissions and called it a whim. Others said that the industry will only go through a shakeout and will endure.

Dickson Donald Despommier was born on 5 June 1940 in New Orleans from Roland and Beverly (Wood) Despommier. His father was an accountant for a shipping line. His parents divorced when Dickson was young.

In 1962 he received a BS in the biology of Fairleigh Dickinson University, an MS in Medical Parasitology from Columbia in 1964 and a Ph.D. In Microbiology of the University of Notre Dame in 1967.

Dr. Despommier joined the Faculty of Columbia in 1971 as an assistant professor of microbiology. He gave a required course on parasitic diseases to second -year medical students for three decades. His research focused on tropical diseases; He was co-author of a textbook, 'parasitic diseases' and a director of the 'Parasites Without Borders' website.

In addition to his wife, he is survived by his sister, Duane Despommier Kuykendall; His sons, Bruce and Bradley; A stepdaughter, Molly Bloom; A stepson, Michael Goodwin; Four grandchildren; And three great -grandchildren. An earlier marriage, with Judith Forman, ended in divorce.

The idea of vertical agriculture arose when students Dr. Despommier in 2000 said that they were bored with his course on medical ecology. He led the semester by asking a question: “What will the world look like in 2050?” and a follow -up question: 'What would you pretend The world is like in 2050? “

The discussion was aimed at how dense pressure the planet would be in 50 years and how food should be grown than with less water and less pollution by chemical fertilizers. Students said New York City should find all its food up close. They suggested using the roofs of the city for agriculture. But then they calculated that if every roof in all five districts were changed in a garden, the growing area would feed only about 2 percent of the population.

Dr. Despommier then thought of setting up crops in glass and steel skyscrapers, stacked with plants on several levels, just like their human inhabitants. He continued to refine designs with the class of ecology -students of each year. In 2001 he took over the term vertical agriculture.

After he appeared on the comedy Central Late-Night Show “The Colbert Report” in 2008 to discuss his aubergines on the skin, the traffic to his website shot up to 400,000 visitors at night.

Many of the start-ups that the vision of Dr. Despommier turned into a reality built vertical farms that were only two or three floors high compared to the colossi of 30 floors that he had suggested. One was attached to a parking garage in Jackson, Wyo. Others were housed in shipping crates.

But the idea crossed the world, with a non -profit, the association for vertical agriculture, which started in Germany in 2013.

All the time, skeptics wondered whether the costs and the carbon footprint of internships were an improvement in relation to the traditional species that was practiced by humanity for approximately 12,000 years.

“It is such an attractive idea – 'press floor 10 for SLA' – that people picked it up immediately,” said Bruce Bugbee, a professor in crop physiology at Utah State University, in 2016 on the New York Times. “The fundamental problem is that plants need a lot of light. It is free outside. If we do it inside, this requires burning many fossil fuels.”

The industry -shakeout has been cruel, with the editor of the Vertical Landbouw news site today in 2023 stated that risk capital investments in vertical agriculture had fallen by around 90 percent.

Dr. Despommier brainstorming about how modern life could thrive in the face of a dangerously changing climate. In his last book, “The New City: How to Building Ourable Urban Future” (2023), he suggested that cities of wood were now built.

The carbon footprint of making concrete and steel, he explained, is huge, while wood is a carbon gest – trees absorb carbon from the air as they grow – and new technologies for engineering wood could be built very high buildings.

“It sounds like we'll use all the wood,” he said last year, “but the fact is that if the vertical agriculture succeeds, there will be much more land to grow trees.”