Wikimedia/CC BY-SA 3.0

Google DeepMind has teamed up with classical scholars to create a new AI tool that uses deep neural networks to help historians decipher the text of damaged inscriptions from ancient Greece. The new system, called Ithaca, builds on an earlier text recovery system called Pythia.

Ithaca doesn’t just help historians recover text — it can also identify a text’s origin location and date of creation, according to a new paper the research team published in the journal Nature. Ithaca has even been used to settle an ongoing debate among historians about the correct dates for a group of ancient Athenian decrees. An interactive version of Ithaca is available for free, and the team makes the code open source.

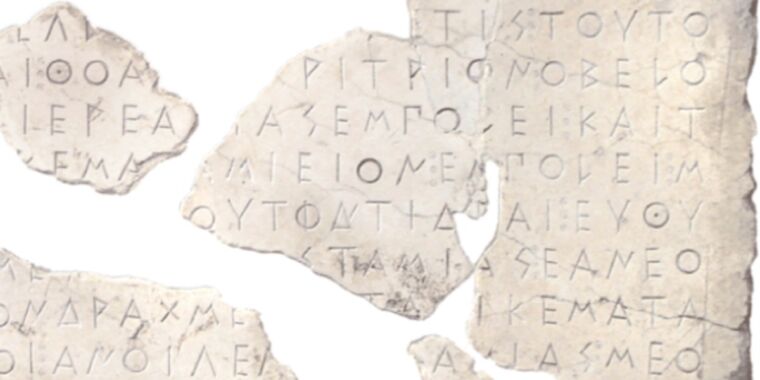

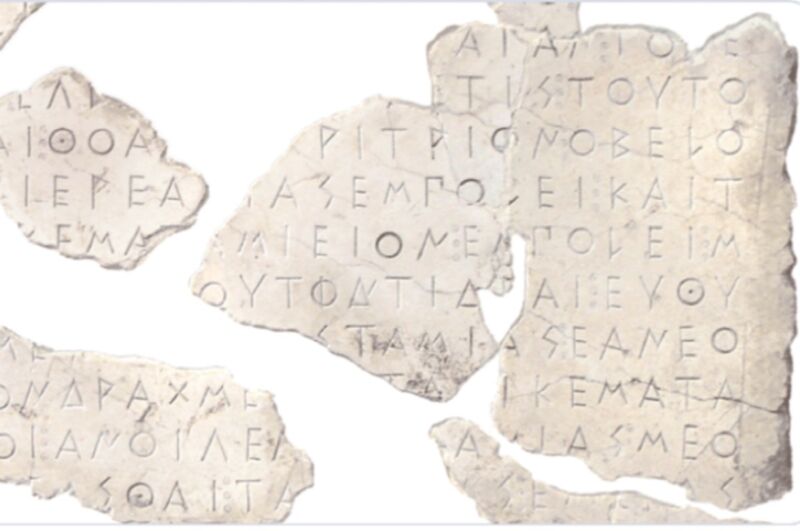

Many ancient sources—whether written on scrolls, papyri, stone, metal, or pottery—are so damaged that large chunks of text are often illegible. It can also be a challenge to determine where the lyrics come from, as they have likely been moved several times. As for accurately determining when they were produced, radiocarbon dating and similar methods cannot be used as they can damage the priceless artifacts. So the daunting and time-consuming task of interpreting these incomplete texts falls to so-called epigraphists who specialize in those skills.

As the folks at DeepMind wrote in 2019:

One of the problems with distinguishing the meaning of incomplete text fragments is that there are often multiple possible solutions. In many word games and puzzles, players guess letters to complete a word or phrase. The more letters specified, the more limited the possible solutions become. But unlike these games, which require players to guess a sentence individually, historians restoring a text can estimate the likelihood of several possible solutions based on other contextual clues in the inscription, such as grammatical and linguistic considerations, layout and form, textual parallels, and historical context.

To help speed up the process, Yannis Assael, Thea Sommershield and Jonathan Prag of DeepMind teamed up with researchers from the University of Oxford to develop Pythia, an ancient text recovery system named after the high priestess who served at the Oracle of Delphi. by the sayings of the god Apollo.

Acropolis Museum/Socratis Mavrommatis

The researchers’ first step was to convert the Packard Humanities Institute (PHI) database — the largest digital collection of ancient Greek inscriptions — into machine-active text they called PHI-ML. That amounted to about 35,000 inscriptions and more than 3 million words from the 7th century BC to the 5th century AD. Next, the researchers trained Pythia (using both words and the individual characters as input) to predict the missing letters of words in those inscriptions. Pythia is trained to use the pattern recognition capabilities of deep neural networks.

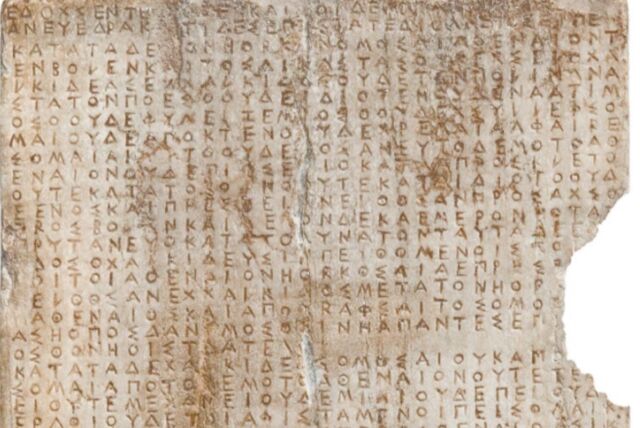

When confronted with an incomplete inscription, Pythia produced as many as 20 different possible letters or words that could fill in the gaps, as well as the confidence level for each possibility. It was up to the historians (ie the “domain experts”) to sort through those possibilities and make a final decision based on their substantive expertise.

The team tested the system by comparing Pythia’s results on completing 2,949 inscriptions with those of Oxford students in epigraphy. Pythia’s output had a 30.1 percent error rate, compared to a 57.3 percent error rate for the students. Pythia was also able to complete the task much faster, taking just a few seconds to decipher 50 inscriptions, compared to two hours for the students.

And now Assael and his cohorts are back at Ithaca. In addition to the ability to restore text, Ithaca makes predictions about the geographic assignment of incomplete inscriptions. The probability distribution across all possible predictions is conveniently visualized on a map, “to shed light on possible underlying geographic connections across the ancient world,” the team writes in an accompanying blog post. For chronological assignment, Ithaca produces a distribution of the predicted dates between 800 BCE to 800 CE.

Epigraphic Museum/Wikimedia CC BY 2.5

Tests showed Ithaca on its own is capable of achieving 62 percent accuracy when restoring damaged text, compared to 25 percent accuracy for human historians. But the combination of man and machine increases the overall accuracy to 72 percent, which Assael et al† believe demonstrates “the potential for human-machine collaboration” in the field. As for assigning inscriptions to their original location, Ithaca can do this with 71 percent accuracy and the inscriptions date within 30 years.

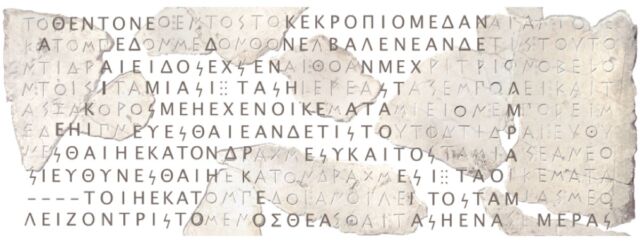

Ithaca has already had a chance to demonstrate its usefulness to historians in a test case involving a series of Athenian decrees that have been at the center of a dating controversy. Historians had previously linked the dates of the decrees to no later than 446 BCE. That assessment was based on certain letterforms (known as the Attic three-bar sigma) used by the Athenian bureaucracy during this period. After 446 BCE, the Athenians switched to an Ionic four bar sigma for their decrees.

This was the standard method of dating for Athenian inscriptions until other historians began to question the assumptions, especially since several decrees dated in this way seemed to conflict with Thucydides’ historical accounts. These historians discovered evidence that the Attic letterform continued to be used in official records long after 446 BCE. They concluded that the dates of many of these decrees should be earlier – around 420 BCE. Ithaca predicted a date of 421 BCE, very much in agreement with that conclusion.