C. W. Moeliker, 2001

On June 5, 1995, Dutch ornithologist Kees Moeliker was quietly working in his office in the new wing of the Natural History Museum in Rotterdam when an unusually loud bang sounded one floor below. The wing’s all-glass facade sometimes took on mirror-like features, so there was a regular supply of birds crashing into the glass. In this case, the collision of a mallard drake (Anas platyrhynchos) lying dead on his stomach in the sand.

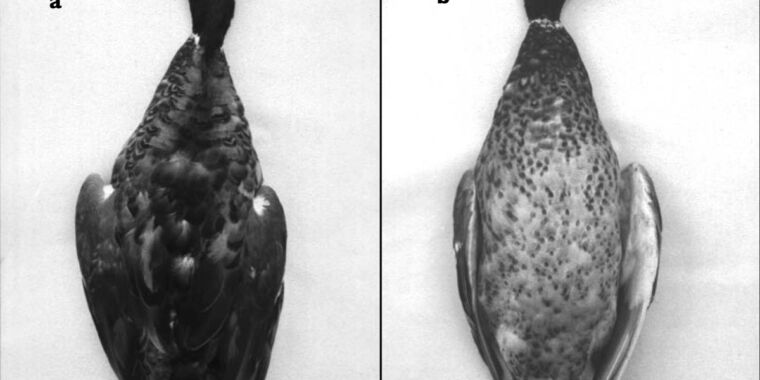

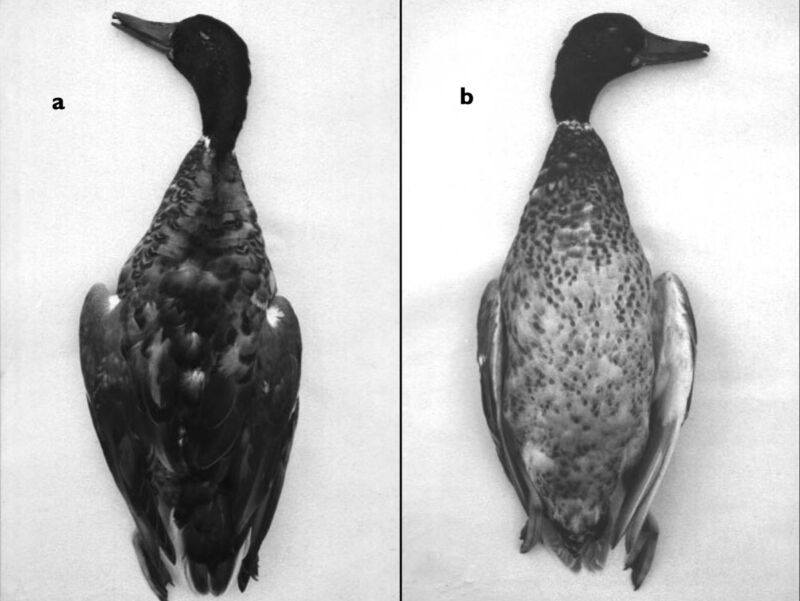

Things took an unusual turn when Moeliker spotted a second, live male mallard nearby, who began pecking at the back of the dead duck’s head. After a few minutes, the live duck “climbed onto the corpse and began to copulate with great force,” Moeliker recalls, stopping only for a few short pauses. The ornithologist managed to snap some photos of this strange behavior before stepping in and collecting the dead duck specimen – despite the vociferous objections of its living ‘partner’. It was the first documented case of homosexual necrophilia in the species.

Christian Richter

Moeliker published his findings in a 2001 paper that would eventually earn him the 2003 Ig Nobel Prize in biology. It also inspired the annual “Dead Duck Day” celebration, held at the spot where the unlucky duck perished, marked by a memorial plaque. The brief memorial ceremony — which also recognizes “the billions of other birds that die(d) from glass building collisions and challenges people to find solutions to this global problem,” according to Moeliker — is typically followed by a six-course duck dinner at a local Chinese restaurant called Tai Wu. The event is co-organized by the museum and the European Bureau of Improbable Research.

In his paper, Moeliker noted that the museum’s park has several water features, such as ponds and ditches, favored by a feral population of mallards numbering between 40 and 50 individuals at the time of the incident. His hypothesis is that the two ducks were engaged in an aerial chase or “chase flight”—common mallard duck behavior—when the doomed duck hit the glass facade. It is highly unlikely that the [other] drake just came by, saw the body and started raping it,” he wrote. You might quibble with the use of the word “rape” to describe the copulation that Moeliker observed, but he wrote that given the deceased nature of the penetrated party, “the act was non-consensual anyway.”

C. W. Moeliker, 2001

Two male mallard ducks mating wouldn’t really be that surprising. Same-sex clutches have been recorded in some 450 different species, from flamingos and bison to warthogs, beetles and guppies. Female koalas sometimes mount other females, while male Amazon river dolphins have been known to enter each other’s blowholes. Lepidopterist WJ Tennent, while diligently tracking Mazarine Blue butterflies in Morocco in 1987, observed several males of the species mating with each other rather than females of the species.

Nor is necrophilia limited to wild ducks. A British naturalist named George Murray Levick traveled to Antarctica on the 1910-1913 Scott Expedition and spent several months studying the breeding habits of a colony of Adélie penguins off Cape Adare. Levick was shocked to see not only male penguins mating with other males, but also a young male Adelie penguin attempting to mate with a dead female. Necrophilic behavior has also been observed in ground squirrels, New Zealand sea lions, rock pigeons, pilot whales and crows, among others. Canadian biologist and linguist Bruce Bagemihl prefers to call this sort of thing “biological exuberance,” and his 2000 book of that title makes for fascinating reading for those curious to learn more.

Kees Moeliker: How a dead duck changed my life (2013).