On Tuesday, NASA announced that the first test of a potential planetary defense system was a remarkable success. The Double Asteroid Redirect Test (DART) successfully smashed a spacecraft into an asteroid in late September, hoping to change its orbit around a larger companion. However, any changes in the orbit would be difficult to pick up and potentially require months of follow-up observations. But the magnitude of the orbital shift was big enough that ground observatories were already picking it up.

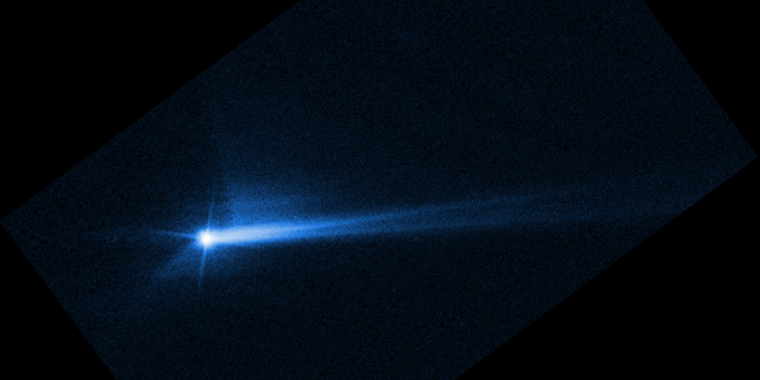

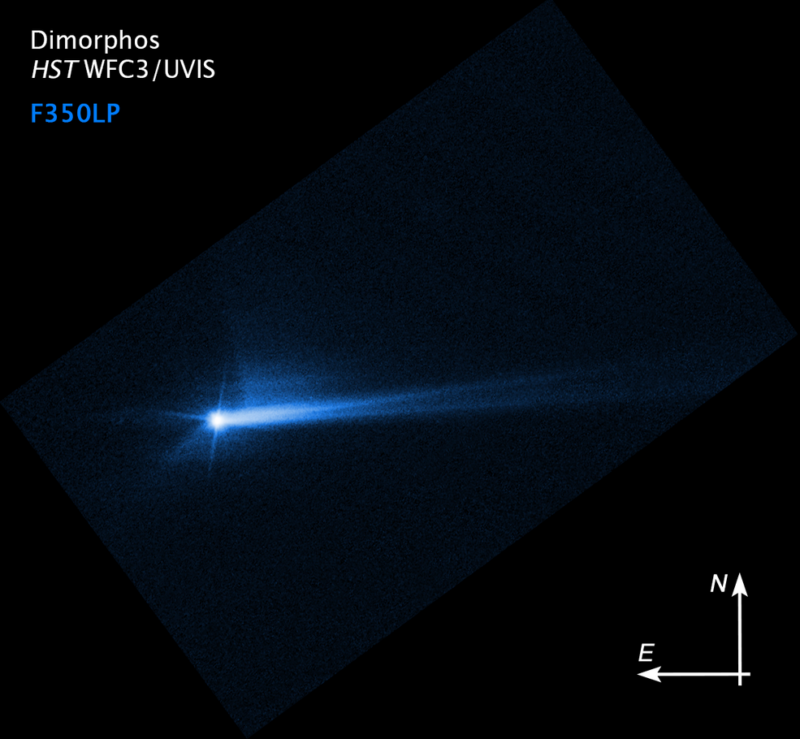

Meanwhile, a lot of hardware is also picking up the debris shot from the impact, giving scientists a lot of information about the collision and the asteroid.

New job, who’s there?

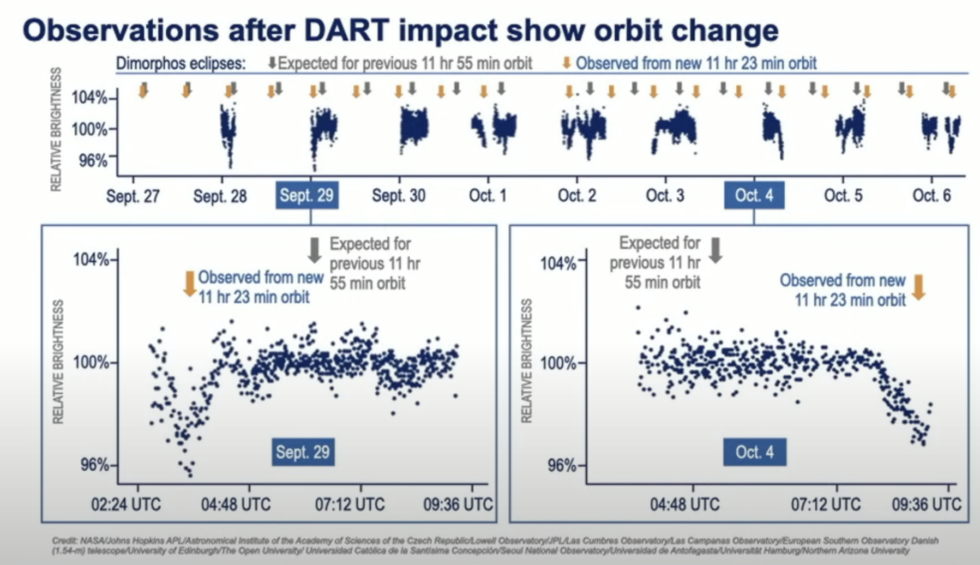

Dimorphos is less than 200 meters wide and cannot be solved from Earth. Instead, the binary asteroid looks like a single object from here, with most of the light reflected off the much larger Didymos. What we can see, however, is that the Didymos system darkens sporadically. Usually, the two asteroids are arranged so that the Earth receives light that is reflected from both. But Dimorphos’ orbit sporadically takes it behind Didymos from Earth’s perspective, meaning we only receive light reflected from one of the two bodies – this causes the eclipse.

By measuring the time periods of the eclipse, we can determine how long it takes Dimorphos to orbit and thus how far apart the two asteroids are.

The impact of DART was designed to be frontal and slow Dimorphos. This would cause it to fall into a lower orbit that takes less time to complete. So while we have slowed down the asteroid, we expect its orbit to be completed faster. How fast? In the modeling done before the impact, NASA concluded that it would be at least more than a minute shorter, but probably more significant. “The team had looked at a wide range of parameters for the possible physical properties of Dimorphos and based on those models, we had estimated that we would make a change from a few minutes to several tens of minutes,” said Lori Glaze of NASA.

Over time, the difference between expectations of when you would see a dimming, given Dimphos’ previous orbit, and when the dimming occurs should increase. And a variety of telescopes have made observations that have a large enough time window to capture both the expected orbital dimming and the full range of potential timings based on NASA modeling. The results clearly show that the track has been shortened.

By how much? Before DART, Dimorphos’ orbit lasted 11 hours 55 minutes; post-impact, it dropped to 11 hours and 23 minutes. For those averse to math, that’s 32 minutes shorter (about 4 percent). NASA estimates the orbit is now “tens of meters” closer to Didymos. This orbital shift was confirmed by radar images, which can resolve the two asteroids (albeit barely, as Dimorphos occupies a single pixel in these images).