On July 19, Jonathan Cardi and his family watched as the departure board at Raleigh-Durham International Airport in North Carolina went from green to a sea of red. “Oh my god, it was insane,” Cardi said. “Delayed, delayed, delayed, delayed.”

Cardi, a law professor at Wake Forest University and a fellow of the American Law Institute, was scheduled to fly on Delta Airlines to a conference in Fort Lauderdale, Florida. He and thousands of other travelers stood in line all day as the airline staff kept telling people that flights would be leaving at any moment, he recalled. But when it became clear the planes weren’t going anywhere, he made the 11-hour trip in a rental car instead. Others who were going to the conference were sleeping at the airport, Cardi later discovered.

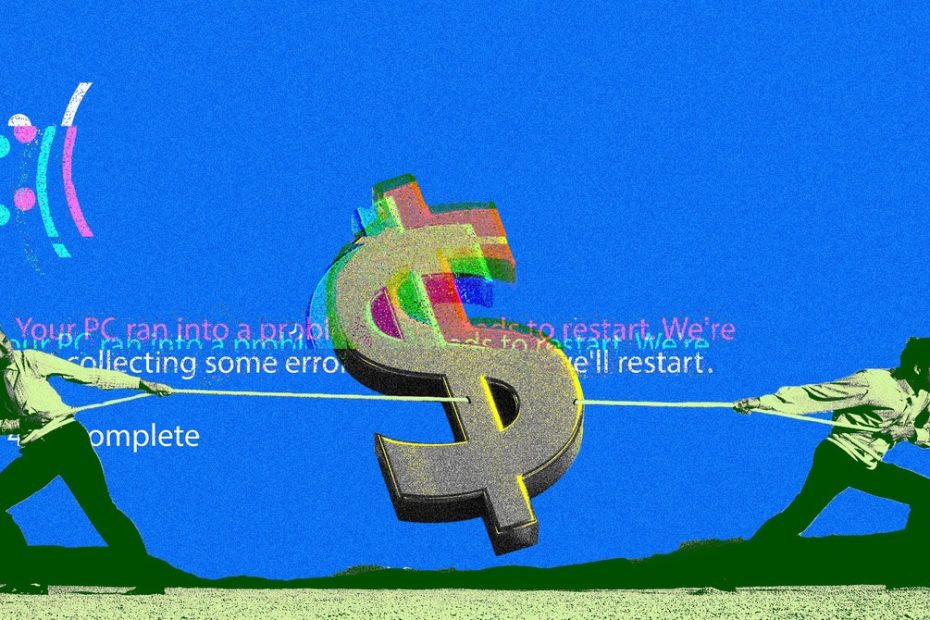

The chaos was sparked by a software update released by cybersecurity firm CrowdStrike, which contained a flaw that caused millions of Microsoft Windows computers to crash. The IT outage, which disrupted airlines, financial services and several other industries, is estimated to have caused more than $5 billion in financial losses. “Because so much money was lost, there will be legal action,” said Cardi, who specializes in the field of law that deals with civil liability for losses or damages.

That legal tug-of-war has already begun.

On July 29, Delta notified CrowdStrike and Microsoft of its intention to litigate over the $500 million it claims it lost as a result of the outage. A class action lawsuit has been filed by law firm Labaton Keller Sucharow on behalf of CrowdStrike shareholders, alleging they were misled about the company’s software testing practices. Another law firm, Gibbs Law Group, has announced that it is considering filing a class action lawsuit on behalf of small businesses affected by the outage.

In response to WIRED's query about the shareholder class action, CrowdStrike said, “We believe this case has no merit, and we will vigorously defend the company.” In a letter to Delta's legal counsel seen by WIRED, a legal representative for CrowdStrike said the company “strongly rejects any allegations that it was grossly negligent or committed willful misconduct.” Microsoft declined to comment. Delta's legal counsel declined an interview request.

Those hoping to recover financial losses will have to find creative ways to frame their case against CrowdStrike, which is largely insulated by software contract-style clauses that limit liability, Cardi says. While it may seem intuitive that CrowdStrike is to blame for its mistake, the company is likely “pretty well protected” by the fine print, he adds.

Limitation clause

Despite CrowdStrike admitting responsibility for the outage, neither direct customers nor businesses disrupted by its proximity (i.e., CrowdStrike customers’ customers) will be able to easily recoup their losses. The first question will be: what specifically would they sue CrowdStrike for? There are a handful of theoretical options (breach of contract, negligence, or fraud), but none of them are easy.

While customers could claim that CrowdStrike breached its contract in some way, “the amount they can recover is likely to be severely limited by the limitation clause,” said Paul MacMahon, an associate professor of law at the London School of Economics and Political Science. The purpose of such a clause is to act as a kind of free pass, limiting the amount a software vendor must pay out. The specifics of the contracts that CrowdStrike enters into with its customers vary from case to case, but the terms and conditions limit CrowdStrike’s liability only to the amount its customers pay for its services.