California was the first state to pass exhaust emission standards, the first to legalize the medical use of marijuana, the first to introduce paid family leave, the first to experiment with guaranteed income at the municipal level, as well as the first state to end a tax revolt that obstructed public services, the first to ban affirmative action and, in 1994, the first to pass a ballot initiative – Proposition 187 – that would have excluded undocumented immigrants from public social services, including education and health care. Prop 187 was a significant episode in the state’s history, crystallizing the nativist’s impact on changing demographics and foreshadowing similar movements across the rest of the country.

California’s character comes from swinging back and forth between two impulses, one restrictive, the other rebellious. Although a majority of voters voted in favor of Prop 187, opposition to the measure was steadfast, especially among young people, who wiped out support for it. It was declared unconstitutional in federal court and was effectively ended in 1999 by Governor Gray Davis. Passing the bill bolstered Latino voter turnout and changed the electoral map for the next 25 years.

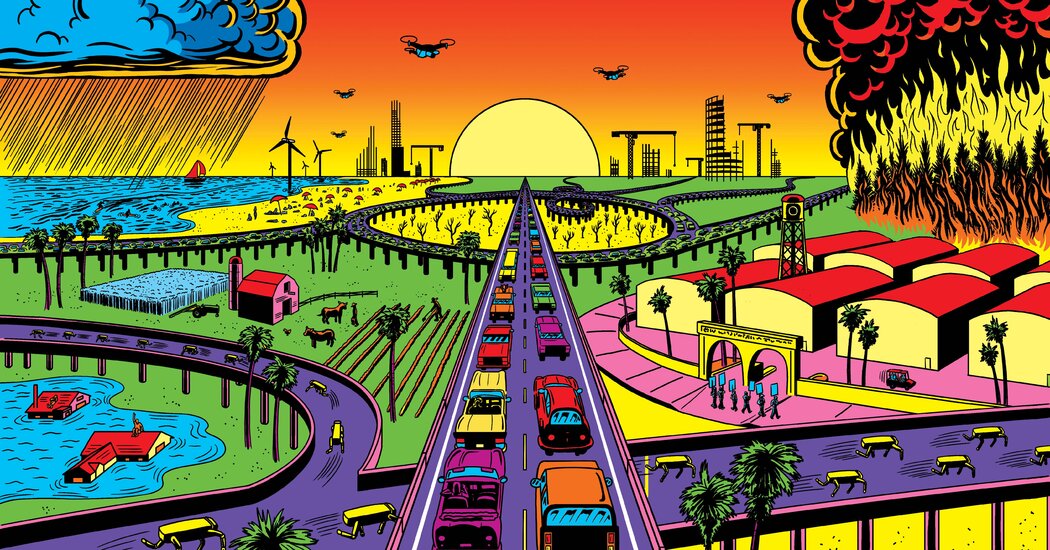

As California faces the threat of climate change, an out-of-state housing crisis and a demographic exodus, we are once again at a crossroads. While listening to the radio after a forest fire a few years ago, I heard a caller pin his hopes on technological innovation as a solution to this problem. But as we approach the future, it might be worth considering how we got here in the first place.

Three hundred years ago the future arrived on foot, clad in the brown robes of a Franciscan friar. In 1769, charged by the Spanish Crown with exploring and “civilizing” the area then known as Alta California, Father Junipero Serra and the fathers began building a chain of Catholic missions on a 600-mile route that ran in a vertical line through the area. The road, which partially followed pre-existing indigenous trails, was named El Camino Real (“the royal highway”). The highway supported the farms and ranches that would eventually become the backbone of the area’s economy, but the mission system presaged a long and relentless campaign of displacement, forced labour, acculturation and violence against the state’s indigenous peoples – which Spaniards envisioned it as a Christian area full gente de razon (“reasonable people”).

In 1848, when California came under American rule, specks of gold were found in the American River. By some estimates, nearly 300,000 people moved to California during the Gold Rush, tripling the state’s population in about 10 years. Moving people and goods to and from the West required a new type of roadway: the Transcontinental Railroad. The newcomers hoped that a combination of luck and hard work would make them wealthy, a belief that came to be known as the California Dream, a precursor to the national mythology surrounding the American Dream.