In June, two American astronauts left Earth with the expectation of spending eight days on the International Space Station (ISS).

But after concerns emerged that it was not safe to fly their Boeing Starliner spacecraft back, NASA delayed the return of Suni Williams and Butch Wilmore until 2025.

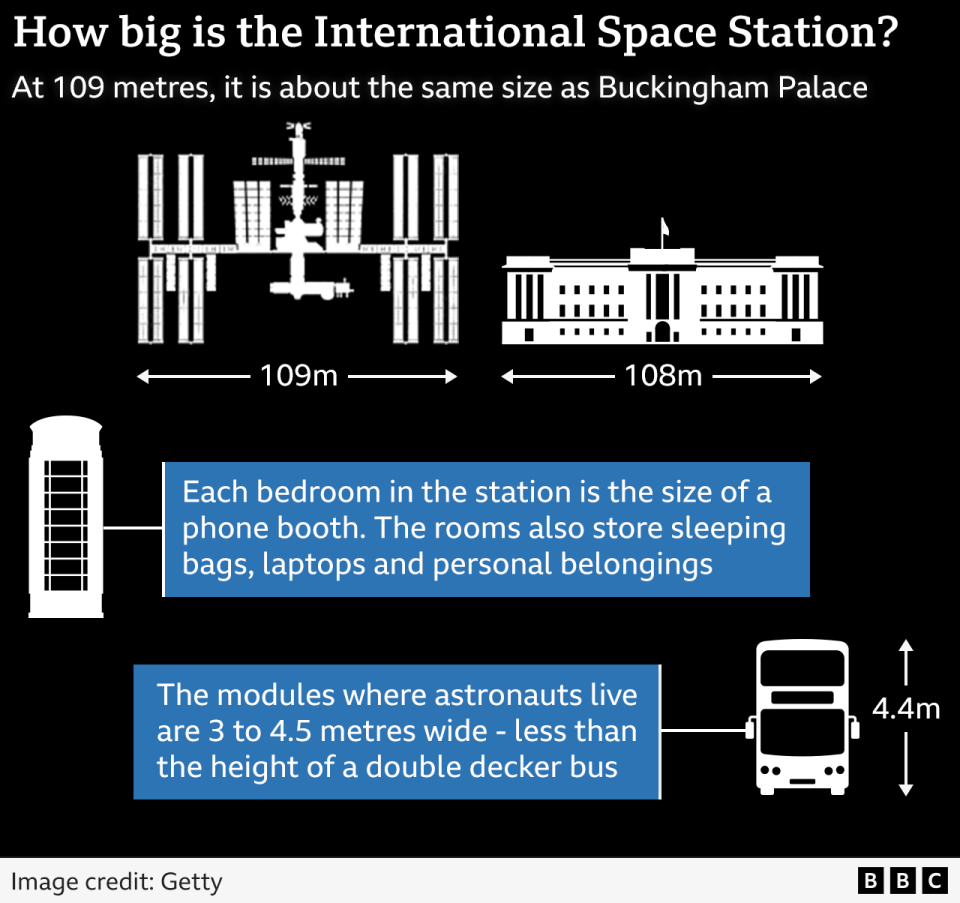

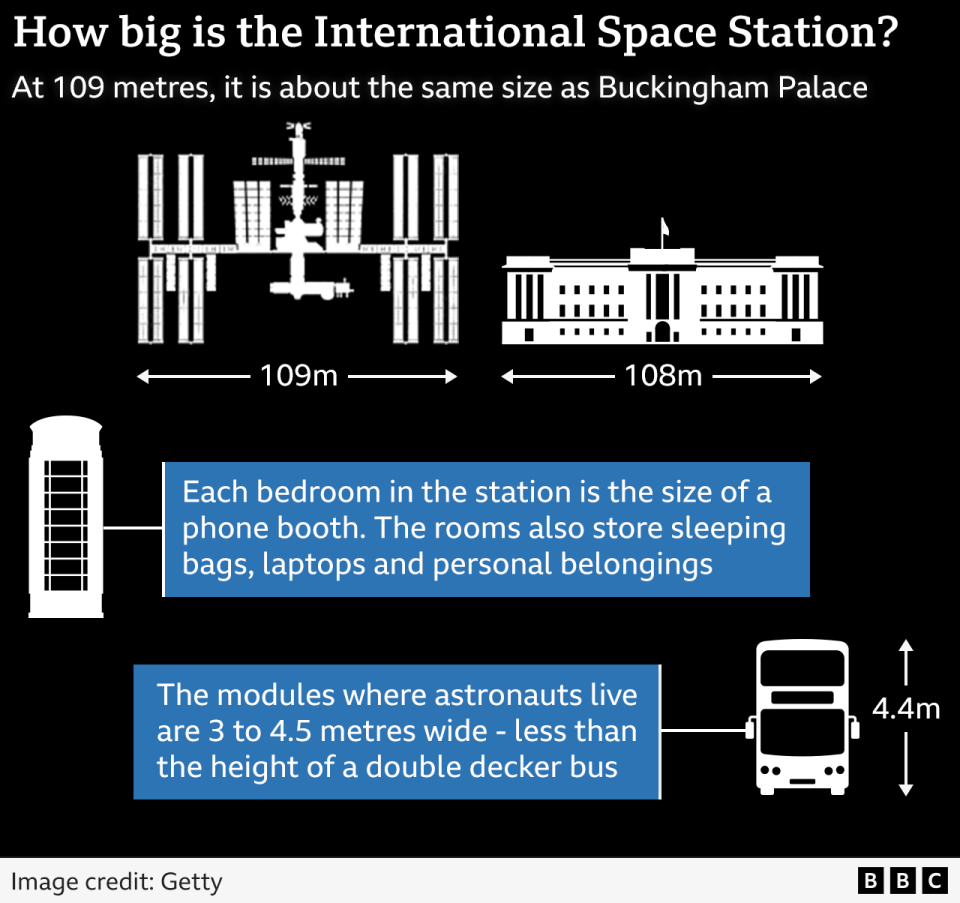

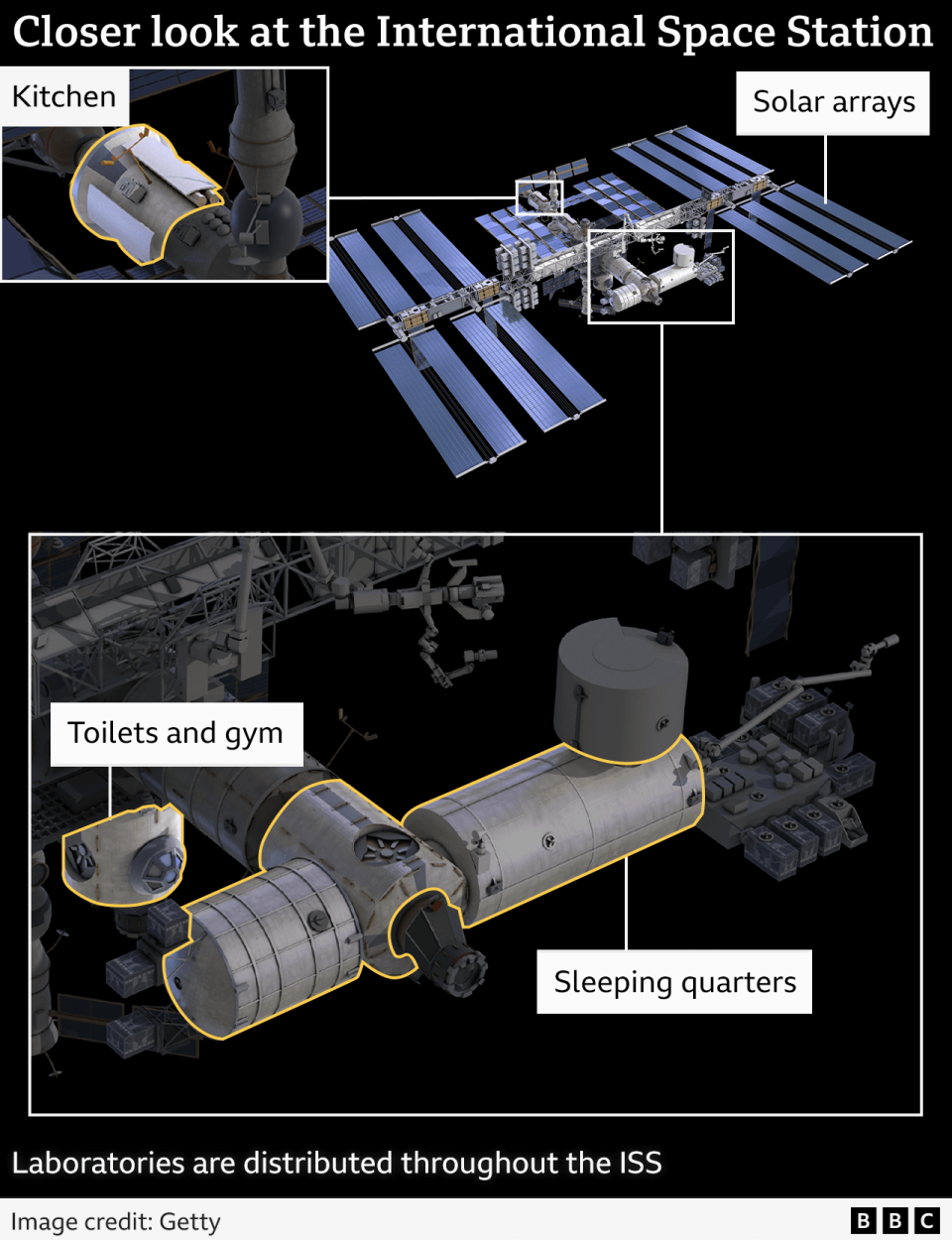

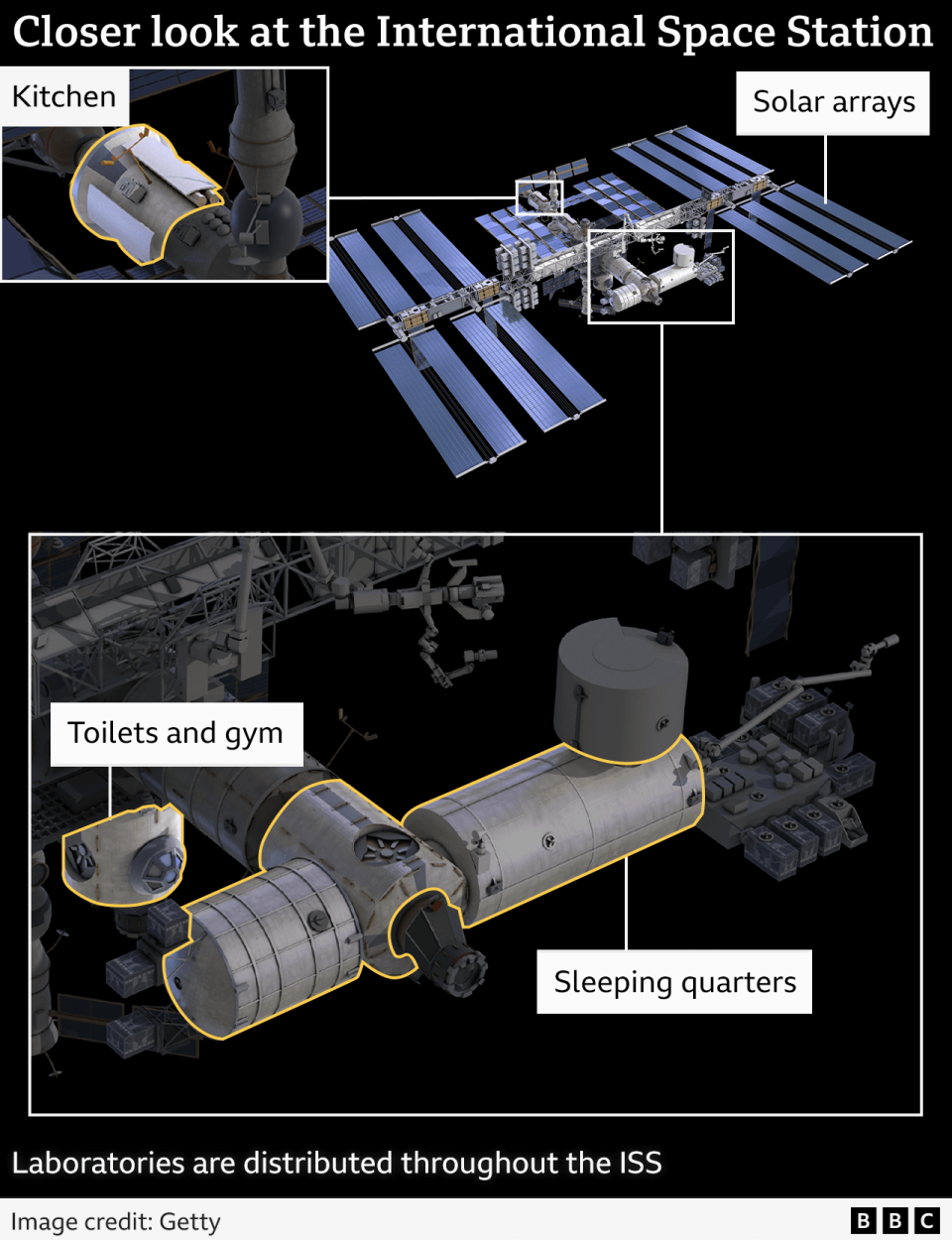

They now share a space the size of a six-bedroom house with nine other people.

Mrs Williams calls it her “happy place” and Mr Wilmore says he is “grateful” to be there.

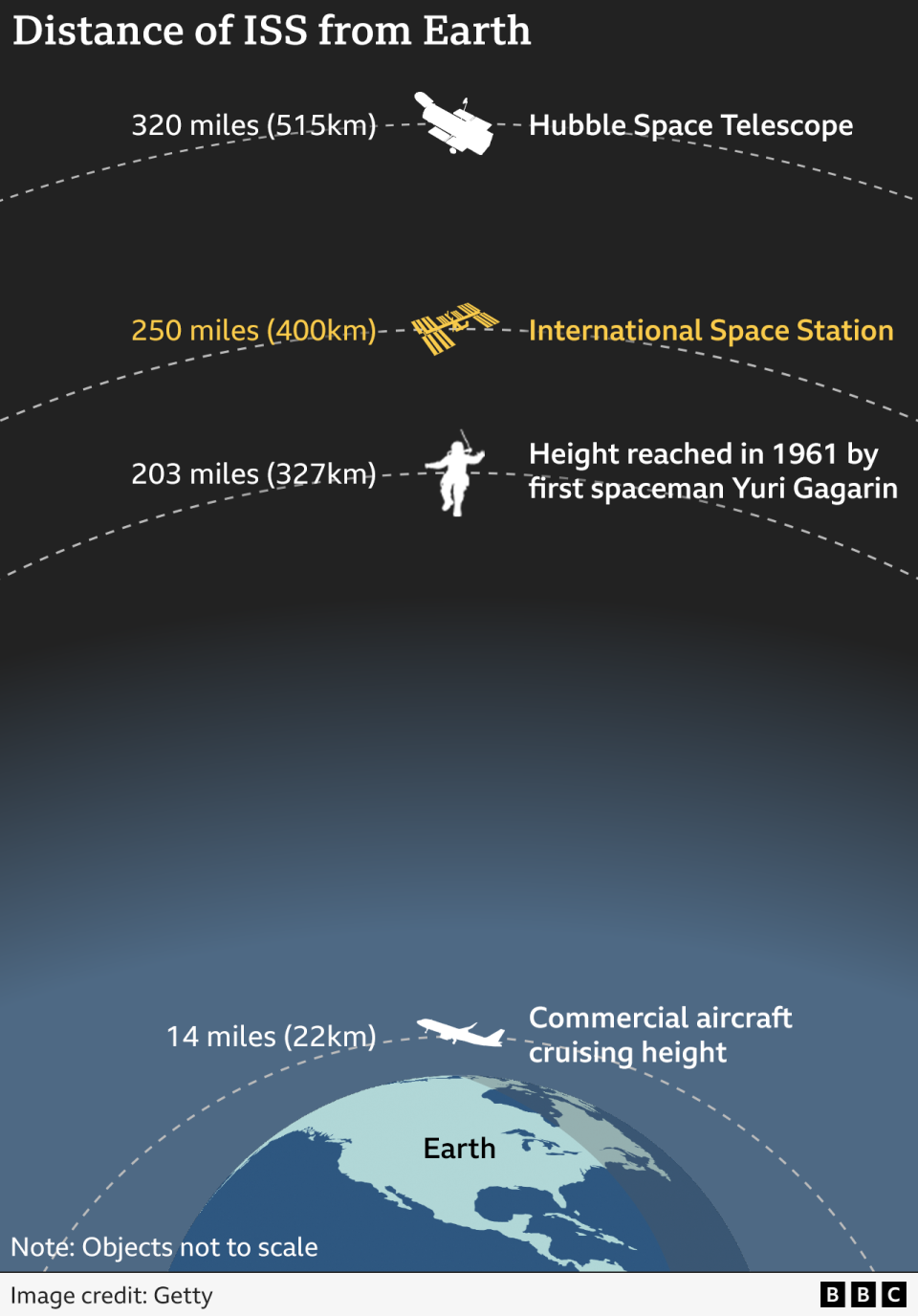

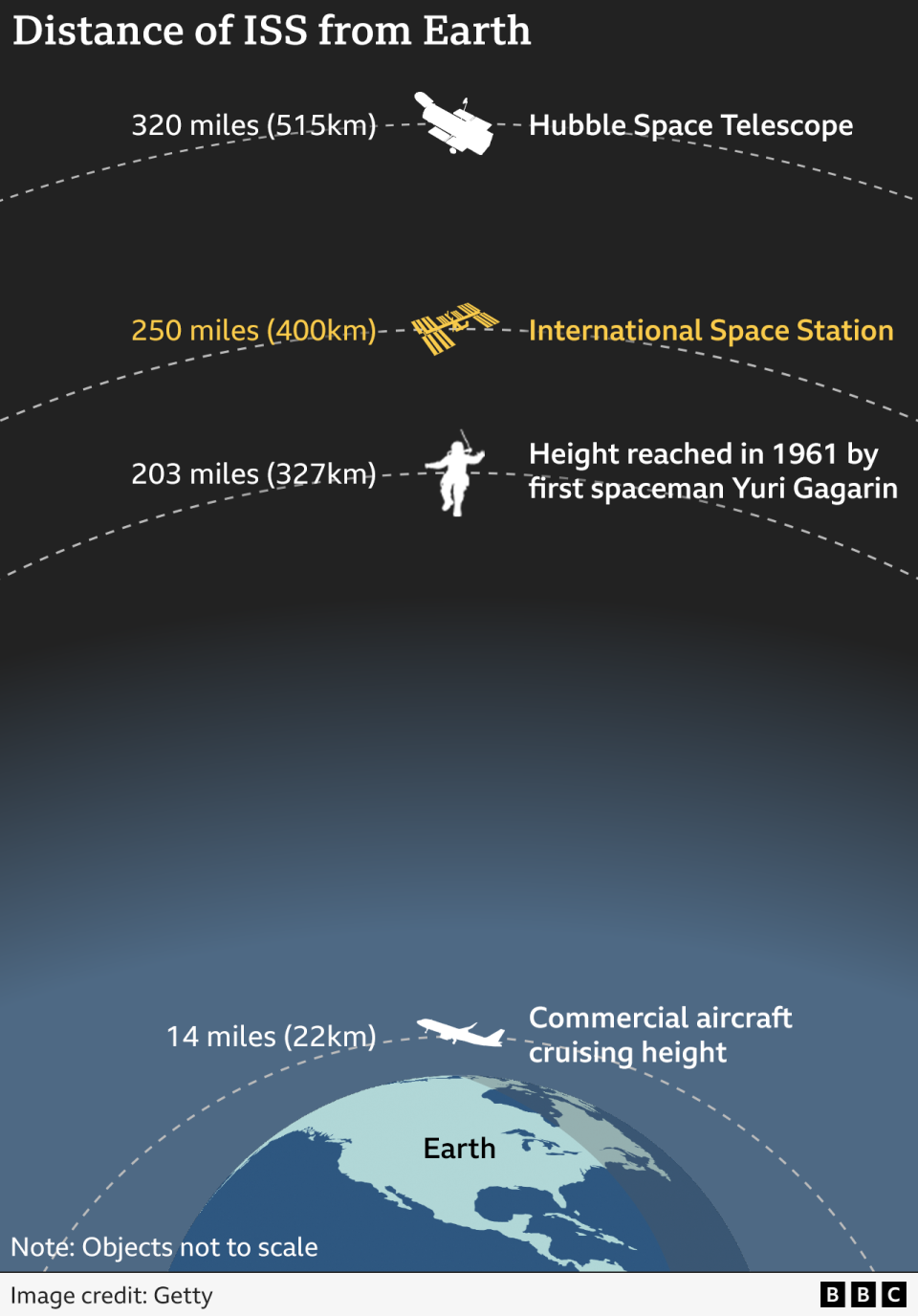

But what does it really feel like to be 400km above the Earth? How do you deal with difficult crew members? How do you exercise and wash your clothes? What do you eat – and most importantly, what is the “space smell”?

Speaking to BBC News, three former astronauts share their secrets to surviving in space.

Every five minutes of the astronauts' day is allocated by mission control on Earth.

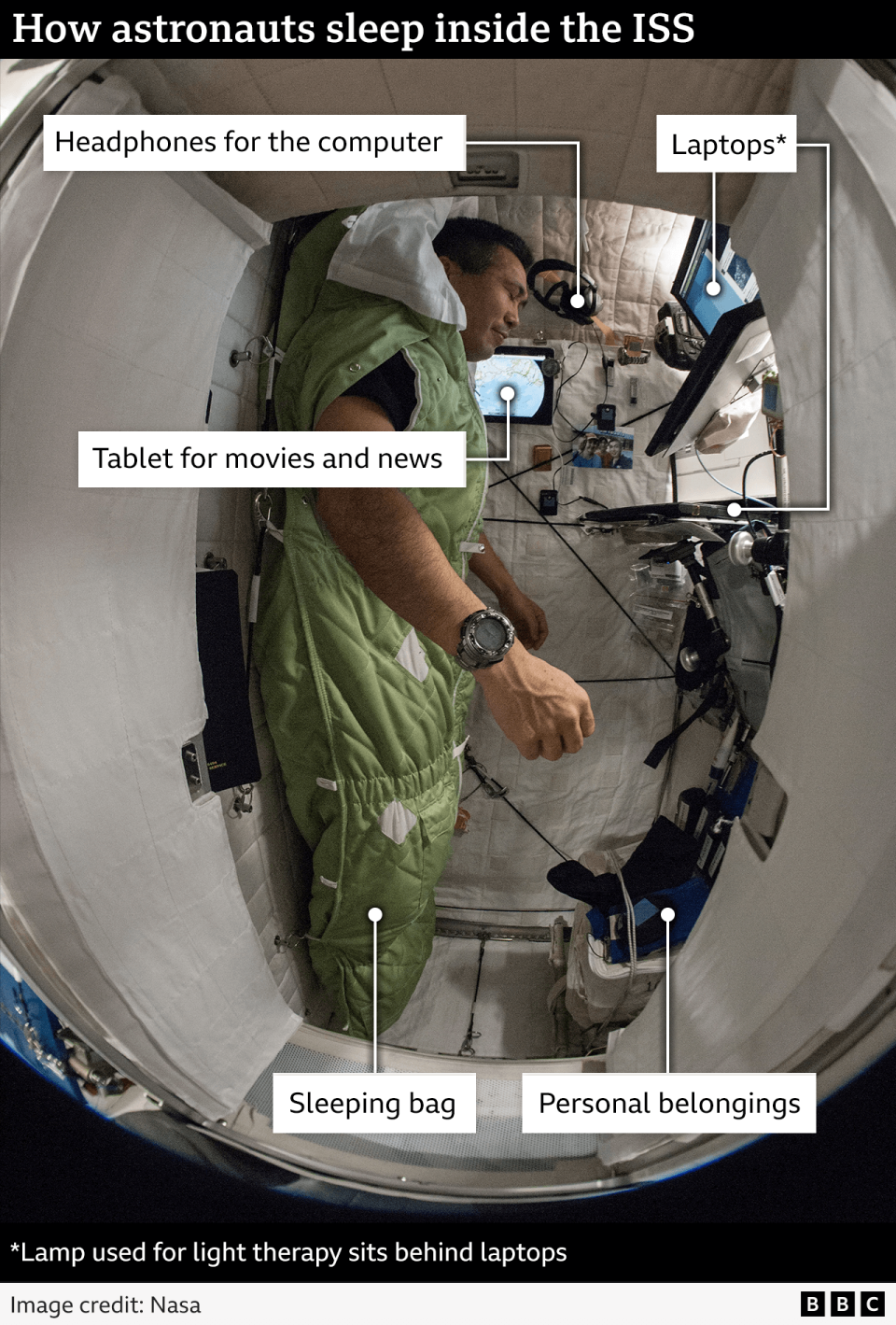

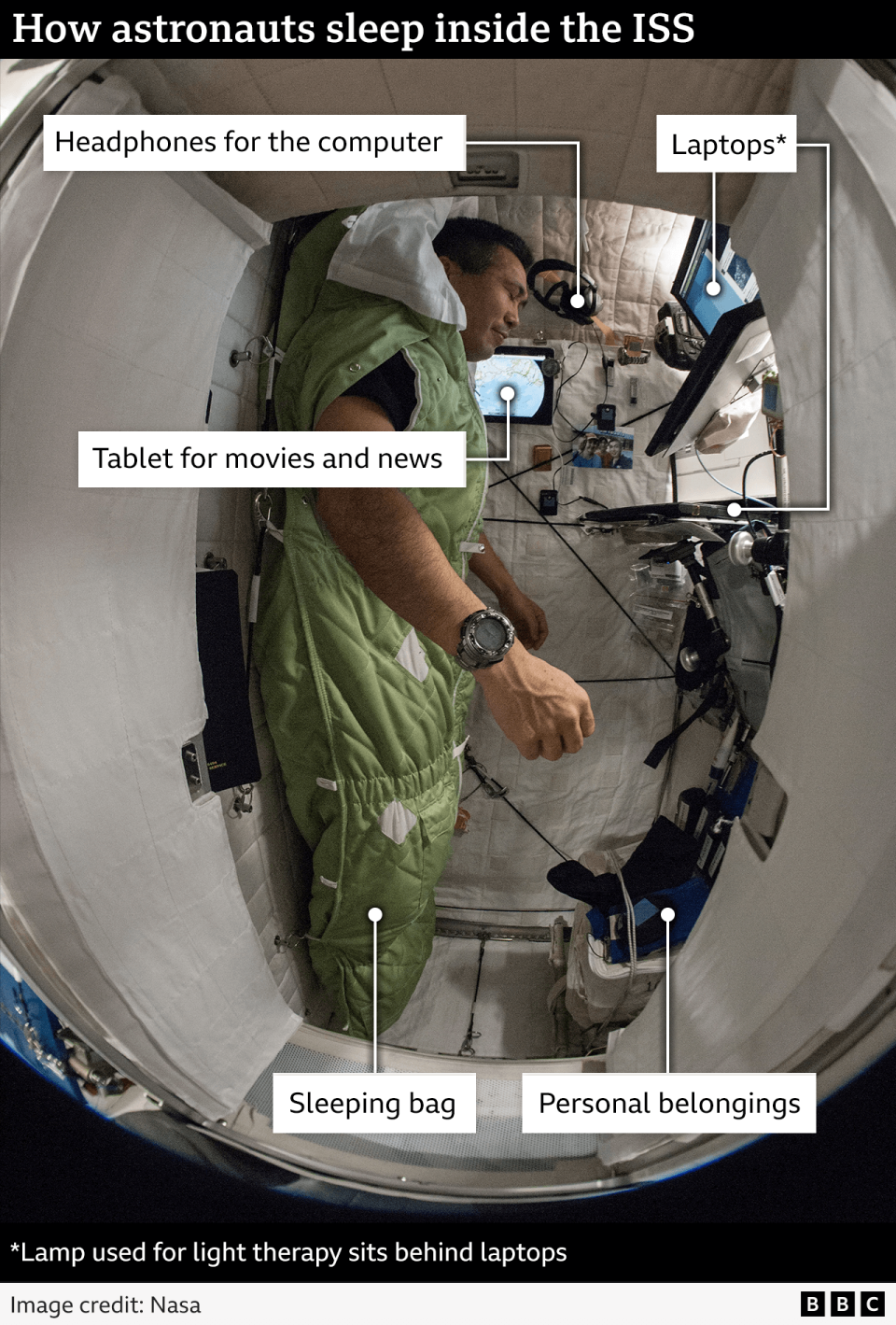

They wake up early. Around 06:30 GMT, astronauts emerge from the phone-booth-sized sleeping quarters in the ISS module called Harmony.

“It has the best sleeping bag in the world,” said Nicole Stott, a NASA astronaut who spent 104 days in space during two missions in 2009 and 2011.

The compartments are equipped with laptops so the crew can stay in touch with family. There is also a compartment for personal belongings such as photos or books.

The astronauts can then use the bathroom, a small compartment with a suction system. Normally sweat and urine are recycled into drinking water, but due to a malfunction on the ISS, the crew must now store urine.

Then the astronauts get to work. Maintenance or scientific experiments take up most of the time on the ISS, which is about the size of Buckingham Palace — or an American football field.

“Inside, it's like multiple buses bolted together. In half a day, you might never see another person,” explains Canadian astronaut Chris Hadfield, commander of the Expedition 35 mission in 2012-13.

“People don't just walk through the station. It's big and peaceful,” he says.

The ISS has six dedicated laboratories for experiments, and astronauts wear heart, brain or blood monitors to measure their responses to the challenging physical environment.

“We are guinea pigs,” says Ms Stott, adding that “space puts your bones and muscles into an accelerated ageing process, and scientists can learn from that”.

If the astronauts can, they will work faster than mission control predicts.

Mr Hadfield explains: “Your game is to find five spare minutes. I would float to the window and watch something go by. Or write music, take pictures or write something for my children.”

A lucky few are asked to take a spacewalk, leaving the ISS for the vacuum of space. Mr Hadfield has done two. “Those 15 hours outside, with nothing between me and the universe except my plastic visor, were as exhilarating and otherworldly as any 15 hours of my life.”

But that spacewalk could add something new to the space station: the metallic “space smell.”

“On Earth we have lots of different smells, like washing from the washing machine or fresh air. But in space there is only one smell and we quickly get used to it,” explains Helen Sharman, the first British astronaut who spent eight days on the Russian space station Mir in 1991.

Objects that go outside, such as a suit or a scientific kit, are affected by the strong radiation of space. “Radiation forms free radicals on the surface and these react with oxygen in the space station, creating a metallic smell,” she says.

When she returned to Earth, she appreciated sensory experiences much more. “There's no weather in space — no rain on your face and/or wind in your hair. I still appreciate those much more to this day,” she says, 23 years later.

In between work, long-stay astronauts must exercise for two hours a day. Three different machines help counteract the effects of living in weightlessness, which reduces bone density.

According to Ms. Stott, the Advanced Resistive Exercise Device (ARED) is suitable for squats, deadlifts and rows, which work all muscle groups.

The crew uses two treadmills that they have to strap themselves into to keep from floating away, and a bicycle ergometer for endurance training.

'One pair of pants for three months'

According to Stott, all that work involves a lot of sweat, which leads to a very important problem: washing.

“We don't have any laundry, just clumping water and some soapy stuff,” she explains.

Because gravity doesn't pull sweat away from the body, astronauts become covered in a layer of sweat — “much more than on Earth,” she says.

“I could feel the sweat growing on my scalp – I had to wipe my head. You didn't want to shake it because it was flying everywhere.”

Those clothes get so dirty that they end up in a truck that then burns up in the atmosphere.

But their everyday clothes stay clean, she says.

“In zero gravity, clothes float on the body, so oils and everything else doesn't affect the body. I wore one pair of pants for three months,” she explains.

Instead, food was the biggest danger. “Someone would open a can of meat and gravy,” she says.

“Everyone was on their guard because little balls of fat were coming out. People were backing away, like in the Matrix movie, to avoid the balls of meat juice.”

At some point, another spacecraft might arrive, with a new crew or supplies of food, clothing and equipment. NASA sends a few supply vehicles a year. Arriving at the space station from Earth is “amazing,” Mr. Hadfield says.

“It's a life-changing moment when you see the ISS out there in the eternity of the universe — when you see this little bubble of life, a microcosm of human creativity in the darkness,” he says.

After a hard day's work, it's time for dinner. Food is usually put together in packages, divided into different compartments per country.

“It was like camping food or military rations. Fine, but it could be healthier,” says Ms Stott.

“My favorites were Japanese curries or Russian cereals and soups,” she says.

Families are sending extra food parcels to their loved ones. “My husband and son chose small treats, like chocolate-covered ginger,” she says.

The crew shares most of the food.

Astronauts are pre-selected for their personal qualities – tolerant, relaxed, calm – and trained to work as a team, which reduces the chance of conflict, Ms Sharman explains.

“It’s not just about tolerating someone’s bad behavior, it’s about calling it out. And we always give each other metaphorical pats on the back to support each other,” she says.

Location, location, location

And finally, we go back to bed and it's time to rest after a day in a noisy environment (fans are constantly running to disperse carbon dioxide particles so the astronauts can breathe. It's about as noisy as a very noisy office).

“We can get eight hours of sleep, but most people stay in the window and look at the Earth,” says Ms Stott.

All three astronauts spoke about the psychological impact of seeing their home planet from 400 km in space.

“I felt so small in that vastness of space,” Ms. Sharman says. “Seeing the Earth so clearly, the swirling clouds and the oceans, I started thinking about the geopolitical boundaries that we construct and how we are actually completely interconnected.”

Ms Stott says she loved living with six people from different countries, “doing this work on behalf of all life on Earth, working together and figuring out how to deal with problems”.

“Why can't that happen on our planetary spaceship?” she asks.

Eventually, all the astronauts have to leave the ISS, but these three say they would return right away.

They don't understand why people think NASA astronauts Suni Williams and Butch Wilmore are “stranded.”

“We've spent our whole lives dreaming, working and training in the hope of staying in space longer,” Mr. Hadfield said. “The greatest gift you can give a professional astronaut is to let them stay longer.”

And Ms Stott says she thought as she left the ISS: “You're going to have to pull my clawed hands off the hatch. I don't know if I'm going to come back.”

Graphic design by Katherine Gaynor and Camilla Costa

![]()