Frankfort, Ky. – Governor Andy Beshear has spent the past few weeks lugging large checks around his state, handing them out to city and county officials for much-needed water improvements.

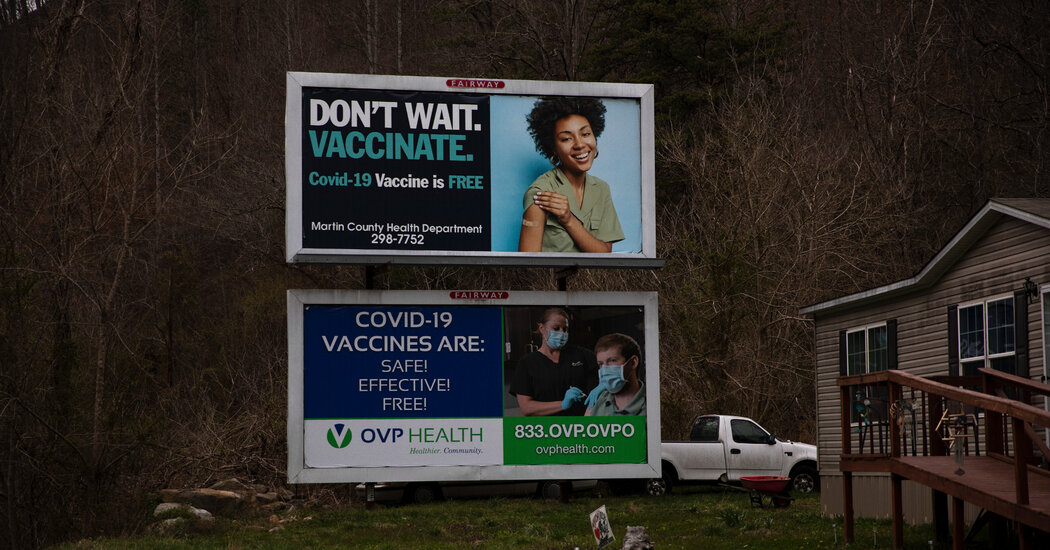

The small town of Mortons Gap was awarded $109,000 to bring running water to six families who don’t have it. The people of Martin County, whose water has been too contaminated to drink since a coal slurry spilled two decades ago, have been awarded $411,000. The checks bear Mr. Beshear’s signature, but the money is coming from the federal government as part of a massive infusion of coronavirus relief that is helping fuel record budget surpluses in Kentucky and many other states.

Therein lies a Washington controversy. The funds, approved by Congress while the pandemic was still raging, may be used for much broader purposes than fighting the virus, including water projects like the one in Kentucky. Most states will get another round of “fiscal recovery funds” next month — part of President Biden’s $1.9 trillion US bailout.

But in Washington, Mr. Biden has run out of money to pay for the most basic means of protecting people during the pandemic: drugs, vaccines, testing and reimbursement of care. Republicans have declined to sign new releases, citing state recovery funds as an example of money that could be used for urgent national priorities.

“These states are awash with money — everyone from Kentucky to California,” said Scott Jennings, a former aide to Senator Mitch McConnell of Kentucky, the Republican leader. “People say, ‘We printed all this money; we sent it. These states have huge surpluses, and now you need more?’”

Republicans were never fans of Mr Biden’s bailout plan, which Democrats dragged through Congress without their support. Despite the many ways it benefits his state, Mr. McConnell once called it an “untargeted multi-trillion dollar band-aid” that would dump “another huge mountain of debt on our grandchildren.”

On Capitol Hill on Thursday, a day after Mr. Biden made a public appeal to Congress for more money, Senate Republicans and Democrats approached an agreement on a $10 billion emergency aid package — less than half of the original request. from Mr Biden. But they hadn’t resolved crucial differences about size and how to pay for it. Republicans want to use unspent money already approved by Congress, but the parties have not agreed on which programs to tap into.

Since the start of the pandemic, the Trump and Biden administrations have injected $5 trillion into the US economy, including the bailout plan. With the midterm elections approaching, the flood of federal stimulus spending will draw even more attention as Republicans accuse Democrats of wasting money and fueling inflation, and demand accurate accounting of how the money has been spent.

David Adkins, executive director and general manager of the Council of State, said such questions were inevitable now that policymakers could take a breather.

“We must rely on the idea that states are laboratories of democracy,” said Mr. Adkins. “Some of these things will fail; some of this money will not be well spent. But that’s the nature of trying to navigate disruptive times.”

The rescue plan earmarked $195 billion to help states recover from the economic and health impacts of the pandemic. When Biden made his first aid request, senior lawmakers in both sides negotiated a plan to pay it in part by taking back $7 billion from states, as part of a $1.5 trillion spending bill.

Governors and ordinary Democrats declined, saying this would disproportionately hurt the 31 states that have not yet received all of their bailouts, and the deal fell apart. Now it looks like the government funds will be spared, although the fracas have thrown a sharp spotlight on how the funds are spent on fiscal recovery.

“I was never in favor of giving this money to the states, but I was always convinced that once you gave it to them, politics wouldn’t allow you to get it back,” Missouri Senator Roy Blunt , the top Republican on the subcommittee that controls health spending, said in a recent interview.

All told, the White House says that 93 percent of US bailout dollars currently available are “mandated by law,” meaning they’ve either already been spent or are determined to be spent.

Most states have either started spending their fiscal recovery funds, or have plans to do so. A recent analysis by the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities found that while most states are still developing budgets for the coming fiscal year, states have already budgeted 78 percent of their fiscal recovery budgets.

Kentucky, where Mr. Beshear, a Democrat, promotes record job growth and economic boom, ended 2021 with a record surplus of $1.1 billion, and another surplus is expected this year. The state has already received $1.1 billion in federal funds and expects another $1 billion in May. It spends the money on broadband, stimulate tourism and supporting the unemployment insurance fund and coronavirus testing, in addition to water improvements.

“These dollars are too important and too transformative to get caught up in a partisan battle,” Mr Beshear said in an interview, adding: “These are dollars that help us as we get out of Covid. We have a choice of coming out of the to stumble or sprint out of the pandemic, and stopping this aid only hurts the people who need it.”

Congress specified four broad goals for the money: responding to the health and economic impact of the pandemic; to provide bonus payments to key employees; to avoid cuts to public services; and investing in sewage, water or broadband infrastructure. But states can also use the money to replace lost revenue, giving them great flexibility in how the money is spent.

Arkansas, for example, has awarded $374,000 to a rape center; $6.3 million to the Arkansas Coalition Against Sexual Assault; and another $6.3 million to the Arkansas Alliance of Boys & Girls Clubs. But most of the money has gone toward improving broadband access and meeting the needs of the health care system.

“The Omicron variant came in, cases skyrocketed, hospitals filled up, and so we had to use a significant amount of our ARPA money to expand hospital space, home testing and other public health responses,” said Governor Asa Hutchinson, a Republican, using the rescue plan acronym. “So that’s obviously the first responsibility, and then we looked at these other needs.”

Other states are using the money in ways only indirectly related to Covid-19, but allowed under Treasury Department guidelines.

Alabama devoted $400 million of its allotment, or about a fifth, to building two new prisons, despite a public outcry from racial justice and civil liberties advocates. Florida spent $2 billion, nearly a quarter of its $8.8 billion allotment, on highway construction — a decision that has drawn criticism from the impartial Florida Policy Institute.

“The intended purpose of the US Rescue Plan Act dollars was to ensure that individuals and communities could recover from the pandemic, and I think in many ways there was a better use for this money,” said Esteban Leonardo Santis, the group tax and income analyst. †

Twenty states, including Kentucky, have spent a total of $15 billion building their depleted unemployment insurance trust funds. Independent analysts say this is effectively a tax break for businesses, which might otherwise have had to make up for lost revenue. But Mr. Beshear defended it, saying that Kentucky businesses have ramped up during the pandemic. A local Toyota factory made face shields and bourbon distillers made hand sanitizer, he said.

from the governor Twitter feed is full of photos of big checks and smiling city and county officials; he is running for reelection in 2023.

“If there’s one thing a governor knows how to do, it’s drive through their state and hand out huge checks and cut big ribbons with big scissors,” said Mr. Jennings. “They’re hosting game shows out there.”

Experts say, and the White House acknowledges, that the fiscal recovery funds have helped create surpluses in the state budget. Gene B. Sperling, a senior adviser to the president who oversees the US bailout, said the surpluses were proof that Mr Biden’s stimulus package was working — and this was no time to turn back.

“Making sure states and places have a cushion for some pretty serious bumps in the road is smart policy,” said Mr. Sperling, “and a lesson learned from what happened after the Great Recession.”

But those surpluses are likely temporary, and how states use them has played a part in the controversy over Covid relief funds. The Center on Budget and Policy Priorities says 14 states are using temporary budget surpluses “to advocate for expensive and permanent tax cuts aimed more at wealthy people” — a move the center described as a “bad choice.”

Here in Frankfort, the state capital, Kentucky lawmakers, rushing to wrap up their 2022 legislative session, worked this week on a hefty income tax cut. But a proposal to use the state’s budget surplus to give Kentuckians a tax credit of up to $500 seemed unlikely, said the author, state senator Chris McDaniel, the chair of the credit committee.

Mr. McDaniel, a Republican, spent much of the week this week on budget discussions, including planning to use Kentucky’s next tranche of fiscal recovery funds. Another $1 billion is coming, and despite some philosophical doubts, he said he saw no reason not to spend it.

“I firmly believe it was too much money that came down,” said Mr McDaniel. “But I also believe that Kentuckians will eventually bear the tax burden just like everyone else down the line, and I’m not going to penalize future Kentuckians out of a point of philosophical pride.”

Emily Cochrane contributed reporting from Washington.