In the early On Thursday morning, major U.S. railroad companies reached a tentative deal with unions, narrowly preventing a nationwide shutdown of the track less than 24 hours before the strike deadline. A work stoppage would have had devastating effects on the country’s economy and supply chain, with nearly 30 percent of which is dependent on rail. Even a near miss had some impact. Amtrak long-distance passenger services, which use freight tracks, and shipments of hazardous materials are now being reinstated after railroads suspended them to prevent people or cargo from being trapped by a strike.

The preliminary agreement, to be voted on by union members, came about through talks brokered by the Biden administration. It struggled this week to avoid a shutdown that would have caused major disruption and exacerbated inflation by limiting supplies of crucial goods and driving up shipping costs. Rail unions and the railway industry association released statements on Thursday welcoming the deal. But rail freight was unreliable long before this week’s deadlock, and trade groups representing rail customers say much work still needs to be done to restore it to acceptable levels.

Only two-thirds of trains arrived within 24 hours of their scheduled time this spring, an 85 percent drop before the pandemic, forcing train travelers to suspend their business or — starkly — consider euthanizing their starving chickens. Scott Jensen, a spokesman for the American Chemistry Council, whose members rely on rail to transport chemicals, called the latest shutdown threat “another ugly chapter in this long saga of freight problems.”

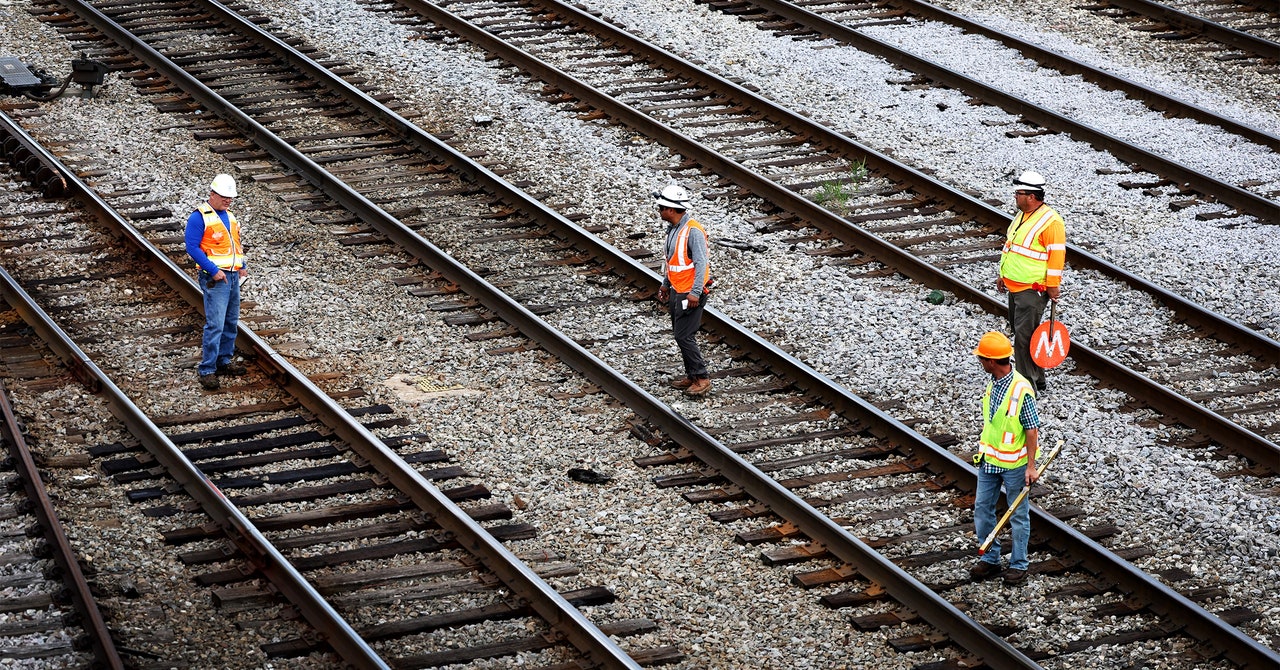

While Thursday’s agreement was praised by companies that rely on rail freight, the ACC, the National Grain and Feed Association and other trade groups also argue that further rail industry reforms are needed. Competition has waned as services have been concentrated at a handful of major railroads, reducing their combined workforce by 29 percent over the past six years. Rail customers have asked legislators and rail regulators to intervene. Suggestions include federal minimum service standards, including penalties for leaving charged cars at yards for long periods, and a rule that would allow customers to move freight to another service provider at certain nodes, to get around the fact that many customers tied to a single carrier.

Major U.S. freight railroads have cut many personnel in recent years as part of an effort to implement a leaner, more profitable business model called Precision Scheduled Railroading. Profits have indeed skyrocketed – two of the largest freight carriers, Union Pacific and BNSF, owned by Warren Buffett, broke records last year. But after many workers decided not to return to the rail industry after pandemic holidays, a staff shortage sent the network into crisis. During federal hearings this spring, rail passengers complained about the worst-ever service level from a network that had been stripped of its resilience.

Many freight transport jobs have always involved erratic schedules and long distances from home, but workers complained that the leaner operations left them with even longer hours, higher injury rates and less predictable schedules. Many employees were denied sick leave and were penalized for taking time off outside their vacation time, which averaged three weeks a year, or vacation and personal time, which for the most senior employees amounted to 14 days a year.