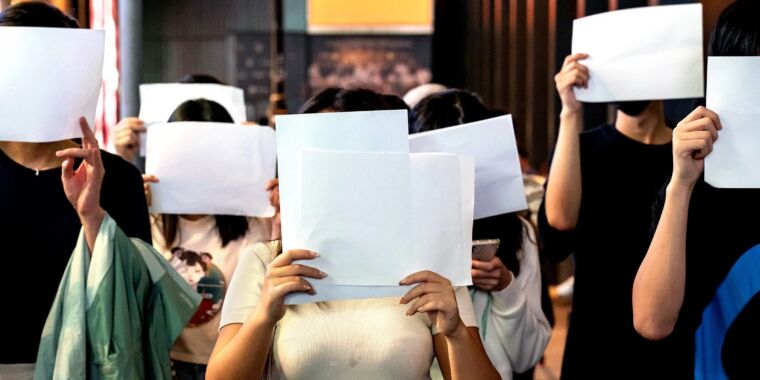

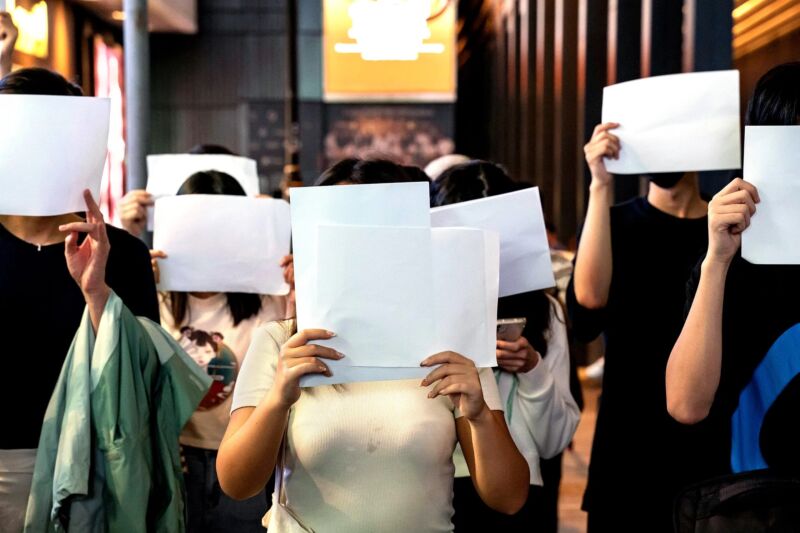

Anthony Kwan/Getty Images

A week ago, protesters took to the streets in the northwestern city of Urumqi to protest China’s strict zero-COVID policy. That night, a much larger wave of protest erupted on Chinese social media, particularly on the super-app WeChat. Users shared videos of the protesters and songs such as “Do You Hear the People Sing” from Les Miserables“Arise, Arise” by Bob Marley and “Power to the People” by Patti Smith.

In the days that followed, protests spread. A largely masked crowd in Beijing’s Liangmaqiao district held up blank sheets of paper calling for an end to the hardline COVID policy. On the other side of town, protesters at the elite Tsinghua University held up prints of a physics formula known as the Friedmann equation because his namesake sounds like “free man.” Similar scenes played out in cities and college campuses across China in a wave of protest that has been compared to the 1989 student movement that ended in a bloody crackdown in Tiananmen Square.

Unlike those earlier protests, the demonstrations that rocked China over the past week were intertwined with and spread through smartphones and social media. The country’s government has tried to strike a balance between embracing technology and limiting citizens’ power to use it to protest or organize, building up extensive censorship and surveillance powers. But last weekend, the momentum of China’s digitally savvy population and their frustration, courage and anger seemed to be breaking free from government control. It took Chinese censors and police days to crack down on dissent on the internet and in the city streets. By then, images and videos of the protests had spread around the world, and China’s citizens had proven their ability to maneuver around the Great Firewall and other controls.

“The mood on WeChat was like nothing I’ve ever experienced before,” says a British national who has lived in Beijing for more than a decade and asked not to be named to avoid scrutiny by Chinese authorities. “There seemed to be a recklessness and excitement in the air as people got bolder and bolder with every post, each new person testing the limits of the government – and their own.” He saw posts he hadn’t seen before on China’s tightly controlled internet, such as a photo of a Xinjiang official with the blunt caption “Fuck off.”

Chinese netizens have built up an idea of what censorship does and does not allow, and many know how to get around some internet controls. But as the protests spread, younger WeChat users seemed unconcerned about the repercussions of their messages, a tech in Guangzhou told Wired, using an encrypted app. Like other Chinese nationals cited, he asked not to be named due to the danger of government attention. More seasoned organizers used encrypted apps like Telegram or shared on Western platforms, like Instagram and Twitter, to publicize it.

The anti-lockdown demonstrations began as unofficial vigils for the victims of a deadly fire in Urumqi, the capital of China’s northwestern province of Xinjiang. The city had been under COVID lockdown restrictions for more than 100 days, which some observers said hindered victims trying to escape and delayed emergency services. Most, if not all, of the victims were members of the Uyghur ethnic minority, who were victims of a campaign of forced assimilation that sent an estimated 1 million to 2 million people to re-education camps.

The tragedy came as frustrations over the zero COVID policy had already begun to mount. Violent clashes had broken out between workers and security at a Foxconn factory in Zhengzhou that produces iPhones. Scott Kennedy of the Center for Strategic and International Studies, a think tank in Washington, D.C., says when he visited Beijing and Shanghai in September and October, it was clear that people had grown “tired” of measures like regular PCR testing. scanning QR “health codes” to go everywhere, and the constant specter of another lockdown. “I’m not surprised things have boiled over,” says Kennedy. The government signaled in early November that some restrictions would soon be eased, but the fire in Urumqi and news of COVID cases rising again “pushed people over the edge,” he says.