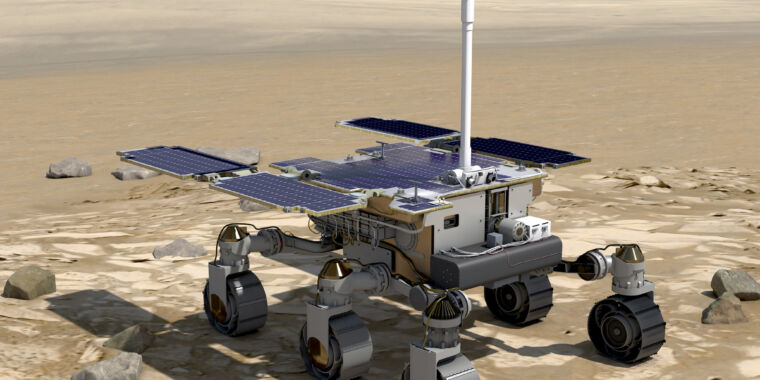

Adrian Mann/Stocktrek Images

The more than two dozen countries that make up the European Space Agency concluded their high-level “ministerial” meeting on Wednesday and set a budget and priorities for the next three years.

Anna Christmann, a German deputy elected to chair the meeting, said the space agency’s plans reflect a bold agenda for Europe to lead the way in climate science and maintain an independent launch capability. The goal is for Europe to become a major space power alongside the United States and China. “We have shown that Europe is ambitious,” Christmann said at a media conference to discuss the results of the meeting.

Germany, France and Italy remain the main players in ESA, together accounting for almost 60 percent of total funding. The member countries agreed to contribute 16.9 billion euros ($17.5 billion) to agency programs over the next three years. This is less than the EUR 18.5 billion requested by ESA Director General Josef Aschbacher, but still significantly higher than the total of EUR 14.5 billion over the previous three years.

“For us, this is a big increase,” Aschbacher said.

An eventful past for a Mars rover

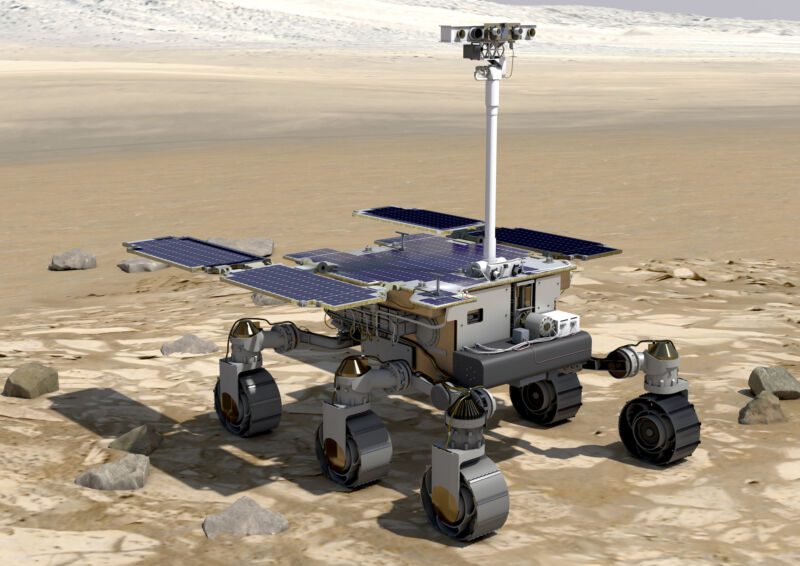

One of the most important decisions made at the meeting was the fate of the Rosalind Franklin rover, which Europa has developed to send to Mars to drill into the surface of the red planet and search for signs of life – formerly or now.

To date, this mission has had a long and rather unhappy history. It was originally conceived about two decades ago, and in 2009 NASA and ESA agreed to jointly develop the project. However, three years later, NASA pulled out of the project, citing budgetary concerns and the need to cover James Webb Space Telescope cost overruns.

Europe then turned to Russia, which agreed to provide a Proton launch vehicle and build a descent module to take the rover to the surface of Mars. After resolving numerous issues, including parachute issues that delayed the project for two years, the ExoMars mission finally set a launch date for summer 2022.

But this date was also postponed after the Russian invasion of Ukraine earlier this year. European officials did not feel comfortable working with Russia on the project, and in July ESA said it was “officially” ending cooperation with Russia on the ExoMars probe. Dmitry Rogozin, the director of Roscomos at the time, responded with an angry message to this Telegram account, calling ESA chief Josef Aschbacher an “irresponsible bureaucrat”.

Back to NASA

Russia’s war against Ukraine has strengthened ties between Europe and the United States on a number of fronts, including space. Cooperation on the ExoMars is therefore back on the table. However, NASA waited to formalize its commitment to see how Europe wanted to proceed.

Aschbacher said on Wednesday that European ministers were considering a number of options, including simply placing the completed Rosalind Franklin rover in a museum. In the end, however, the ministers decided that they would invest hundreds of millions of euros more in the project for Europe to develop its own entry, descent and landing module for the vehicle.

“I am very happy to say that we have found a positive way forward,” said Aschbacher. “Europe will take its responsibility and most of the work will be done with European technology.”

NASA, he said, is expected to contribute a rocket for the mission, a motor for the descent module with adjustable thrust and radioactive heating units. This exchange will be done through bartering. For example, in exchange for a missile launch, Europe could provide an Airbus Beluga aircraft to transport large cargo.

The mission now has a launch date of no earlier than 2028, Aschbacher said. At the moment, SpaceX’s Falcon Heavy booster is the only available U.S. rocket capable of boosting the mission, but the launcher competition won’t be held for years to come. At that point, the United Launch Alliance’s Vulcan rocket and SpaceX’s Starship could be options, as could Blue Origin’s New Glenn vehicle.