“Boris, Florida is in trouble,” warned a text message asking for campaign donations — and promising 900 percent matching funds — for Florida Senator Marco Rubio.

“You’ve got until midnight, Boris,” another campaign caption urged, urging voters to fill out a poll, which came with a photo of former President Donald J. Trump pointing an outstretched index finger like Uncle Sam.

“It’s Mike Pompeo,” said a third message, which appeared to be from the former director of the Central Intelligence Agency. “I’m not asking for $, Boris. I ask you to support these GOP veterans who are running to save America.”

These messages promoted by Republicans, addressed to “Boris,” were among a stream of more than 150 unsolicited text messages sent over a month this fall to Lorraine Barba, a Democrat in Wilmette, Illinois.

Ms. Barba, whose phone number was briefly demanded by a man named Boris, found the unwanted messages on her iPhone intrusive. She repeatedly tried to log out by typing “STOP” – to no avail.

“My phone was constantly pinging,” Ms. Barba said, adding that she was troubled by “the brutality of it.”

She is hardly alone. In October, people in the United States received an estimated 1.29 billion political text messages — about twice as many as in April — according to RoboKiller, an app that blocks Robocalls and spam texts. Many voters complain about it.

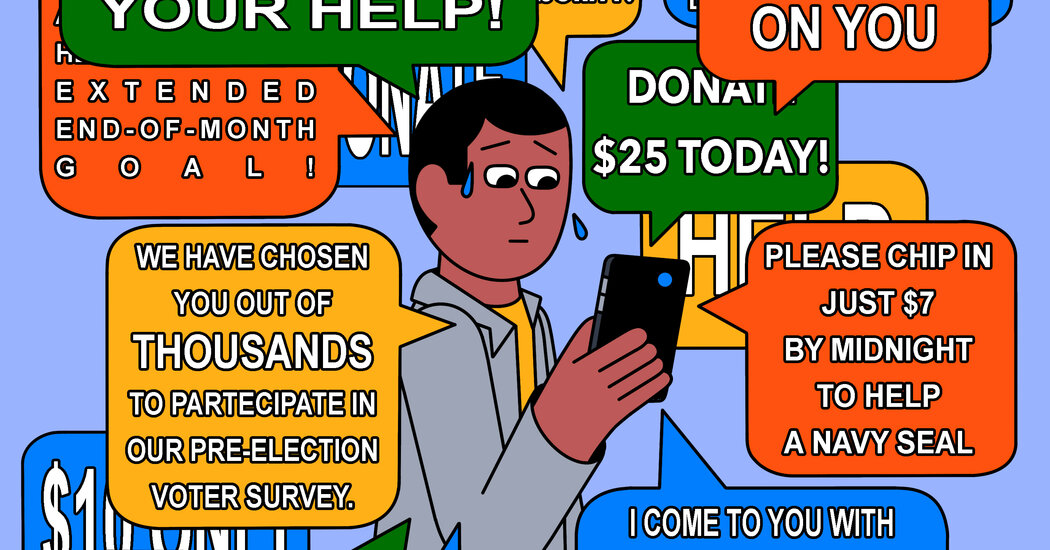

In response to recent questions from The New York Times, more than 940 readers from across the political spectrum shared their experiences, describing a shower of inflammatory messages from both sides. To illustrate their concerns, readers also sent more than 1,000 images of the political texts on their phones. Many were full of divisive language or misleading content.

The campaign messages do not only reflect the deep frustrations of some voters about unwanted political texts. They also document how political texting is becoming a go-to method for spreading doomsday scenarios, lies, and campaign smear.

In other words, texting is a convenient method for political actors to quietly spread the same kind of divisiveness and disinformation that already abounds on social media — only outside the public scrutiny of academic researchers, fact-checkers, and journalists.

The state of the 2022 midterm elections

Election Day is Tuesday, November 8.

“I am disturbed by the division, the lies about voter fraud and the fact that after I unsubscribed, I even got the exact same text message right after,” wrote Ailin Cao, a software engineer in Washington, D.C.

In some cases, the campaign texts did not clearly mention their sponsors. Others solicited donations for, and included links to, unknown entities — making it difficult to distinguish genuine campaign messages from spam and fundraising scams.

Consumers filed 9,477 political text messaging fraud reports with the Federal Trade Commission in fiscal year 2022. Separately, the Federal Communications Commission received about 2,100 complaints related to political texts in the past year.

Still, there’s little federal oversight or control over political texting, in part because regulations haven’t kept up with technological advances. As a result, Americans who want to stop political texts have little other means than to block individual campaign numbers on their phones or report them to their cell carriers.

For example, Federal Elections Commission rules requiring political ads on TV, cable, and radio to disclose their sponsors do not apply to political text messages.

Other rules, enforced by the FCC, require campaigns that use auto-dialers — robocalling technology that can automatically dial random or sequential phone numbers — to obtain consent before calling or texting consumers. But those rules are based on a 30-year-old law: the Telephone Consumer Protection Act of 1991. They don’t apply to today’s political campaigns that use apps to send text messages to hundreds of thousands of people.

In fact, the flow of text messages has only increased this year after the Supreme Court sided with Facebook in 2021 in a lawsuit over unsolicited mobile messages. In that case, Facebook v. Duguid, the court ruled that Facebook’s SMS method fell short of a narrow definition of automatic dialing — a decision that has encouraged some campaigns to freely bombard voters with unsolicited texts.

“The Supreme Court decision has created a loophole that I think many actors, good and bad, use and exploit,” said Jessica Rosenworcel, the chairman of the FCC, in an interview. “That’s why you see this incredible increase in the number of these texts.”

Even politically engaged voters who generally welcome campaign texts said they would like to see reforms.

Joan Condon, a frequent Democratic campaigner who lives in Orleans, Massachusetts, said she enjoyed receiving texts informing her about things like climate change and gun control. But she objected to the apocalyptic tone and artificial urgency – “DEADLINE TONIGHT!” said a fundraising message she received — from many political texts.

“I don’t like scare tactics,” said Mrs. Condon. “You know, please don’t insult my intelligence.” She also objected to “survey” text messages asking voters for voters’ opinions only to ask them for campaign donations later. “It’s like a bait and switch,” she said.

Unlike email, many people still view texting as a sacred channel for communicating with friends, family, or colleagues. That’s why some Americans consider unsolicited political texts to be privacy issues.

“I’m registered as a Republican but never signed up for any of these campaign communications,” wrote Brian Wiley, an adjunct professor of psychology in Ponte Vedra Beach, Fla.

Mr. Wiley, who has received text messages promoting Mr. Trump and Florida Governor Ron DeSantis, said he had filed a complaint with the FCC: “There is no longer any protection for phone numbers,” he added.

Cellular carriers, including Verizon and AT&T, and dozens of services that enable SMS campaigns, have recently attempted to standardize industry practices.

Participating campaigns record the 10-digit numbers they use for texting with a hub called the Campaign Register. They also agree to follow industry best practices, including obtaining permission to send text messages and honoring opt-out requests.

“To prevent unwanted messages from being sent, senders of political messages should consider consumer preferences,” CTIA, a group representing the wireless industry, wrote in a recent blog post. The blog also said campaigns should keep in mind that consumers “donating to a particular candidate does not mean they agree to receive text messages from that candidate.”

It doesn’t always work that way.

In 2020, a retiree in the Phoenix area donated to the first Senate campaign for Raphael Warnock, a Democrat from Georgia. Senator Warnock won a special election in 2021. (The retiree asked not to use her name for privacy reasons.) This year, she said, Senator Warnock’s reelection campaign began sending unsolicited text messages she didn’t want, which she received through her Google Voice number.

But after typing STOP to unsubscribe, she received another text from the Warnock campaign, this time from a different phone number. In total, after repeatedly unsubscribing, she received Warnock text messages from at least 30 different numbers.

In a statement, the Warnock campaign said it honored opt-out requests, using a “highly effective SMS tool” to automatically remove numbers from which it had received “STOP” requests. But if an unsubscribe request comes in from a phone number that isn’t on the campaign’s SMS list — such as a Google Voice number — the campaign said it had “no way of knowing they made the unsubscribe.”

Readers also flagged political texts that spread misinformation or disinformation. One text falsely claimed that President Biden was about to send 87,000 IRS agents to “close and destroy churches across America.”

Jessalyn Aaland, an artist in Emeryville, California, received a number of messages from Republicans making false or exaggerated claims, including an urgent-seeming text stating that Democrats had organized a petition to impeach Supreme Court Justice Amy Comey Barrett, and gathered more. than 50,000 names for it. “We need 305 GOP signatories to drown them out,” the message said.

The messages “are frustrating because they are ridiculous and full of lies and untruths,” Ms Aaland wrote. She added: “These campaigns are hunting people, on all sides of the political spectrum, and I see that in the messages I get.”

In September, the FCC proposed new rules to tackle scams and spam text messages. They would require mobile service providers to block texts that are likely to be illegal.

Ms. Rosenworcel, the bureau’s chair, said such an approach would allow the FCC to fight SMS fraud — without involving the agency in complicated issues of political content and free speech.

But to impose meaningful transparency and consumer protections for political text messaging would most likely require a resolution from Congress, a body populated by lawmakers who rely on mass text messaging to solicit campaign donations.

Jon Leibowitz, a privacy attorney in Washington, DC, said he was also concerned that candidates, political committees, and like-minded advocacy groups could now freely obtain and exchange voters’ cell numbers — a phenomenon he described as “two-pronged privacy violations.” As an example, he sent a reporter copies of unwanted text messages he had received from both parties.

“It’s outrageous that politicians are allowed to do this,” said Mr. Leibowitz, a former chairman of the Federal Trade Commission. “Someone needs to make sure there’s a law that can stop this.”