NASA/APL

Update, 10:30 am: If this is any indication of the quality of the images we can expect in the coming days, we are in for a treat.

ATLAS sightings of the DART spacecraft impact at Didymos! pic.twitter.com/26IKwB9VSo

— ATLAS project (@fallingstarIfA) September 27, 2022

Original article to follow.

About 24 hours before the collision, NASA’s Double Asteroid Redirect Test (DART) probe made its final course correction based on commands from ground controllers. “It’s referenced in a central-body soccer field,” said Bobby Braun of the Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Lab (APL). “That last maneuver was perfect.”

Even at this late stage, DART’s built-in camera couldn’t determine its ultimate target, the small asteroid Dimorphos, so the central body it was targeting is partner Dimorphos’ orbit, called Didymos. DART’s onboard navigation wasn’t able to navigate to its target until it could see it, which was expected to happen only about 90 minutes before impact. At that point, navigation began to adjust DART’s course to get it right at Dimorphos. Ground controllers, separated by about a minute of communication time, could only watch.

“The space is full of moments, and hopefully we’ll have a moment tonight,” Braun said.

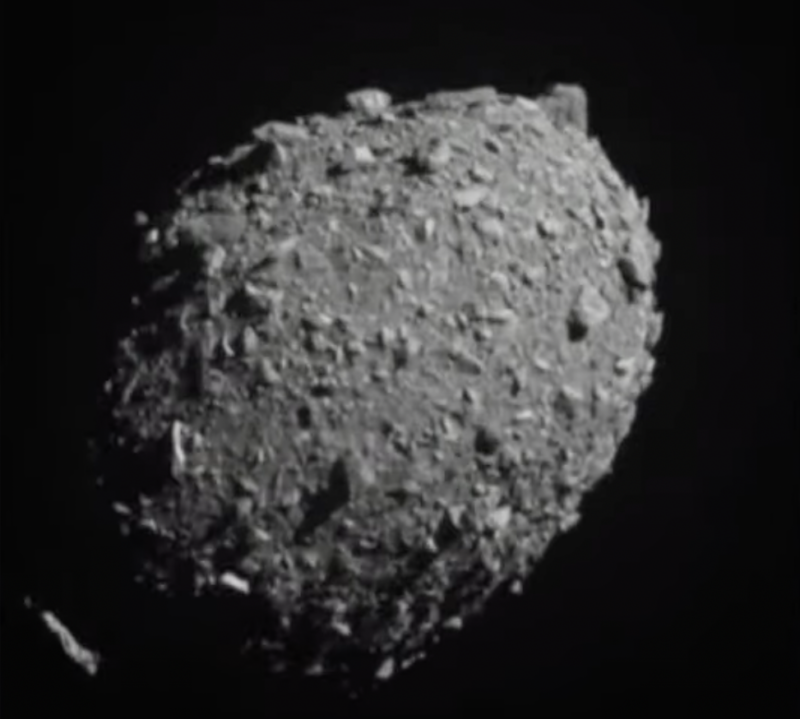

It all worked. Images from the DRACO camera showed Dimorphos looming larger and larger in the final minutes before the collision, eventually filling the entire field of view. And then, at a moment that would normally indicate disaster, the broadcasts stopped halfway through the final image. “What we’re cheering about is the loss of spacecraft, so it’s different,” Braun had said earlier in the day.

As for the details of that impact, we’ll have to wait. The best footage we’ll get is of an Italian Cubesat called LICIACube chasing DART since the two broke up a few weeks ago. The LICIACube is about 50 km from the impact point and will get even closer in the three minutes after the impact before passing behind Dimorphos. But it will take some time to send images to Earth – possibly a day or more for processing and release.

So the first images likely come from ground observatories looking for clarification caused by the plume of debris spreading from the point of impact. When asked how much hardware was used on the ground to look at the plume, Cristina Thomas of Northern Arizona University said, “I don’t know, but there are a lot of them — it’s very exciting to lose count.” Nancy Chabot of APL said the count was up to three dozen, and they will be joined by the Hubble and Webb space telescopes. Some of those images will likely appear online tomorrow.

The exact details of the debris plume can tell us a lot about the asteroid’s interior and help us design hardware for planetary defense. But that level of analysis will take months, with a lot of computer modeling comparing images from multiple sources to try to understand what happened.

NASA is about to hold a press conference on the results, so we’ll see if any details or images are released and update this story accordingly.

Update, 8:40 PM: Not much news from the press conference. Most of the information is that just before midnight there is a window where LICIACube can send impact images through NASA’s Deep Space Network. It’s not clear if everything will work out, but those may be the first details we see. Early estimates are that the impact occurred within 17 meters of the asteroid’s center, but APL’s Lena Adams said the shadow over part of the asteroid made the center a little difficult to identify.

What was also clear was that the final approach was as clean as it appeared. “I kept telling the people next to me, this is nominal, this is nominal, this is nominal,” said APL’s Ed Reynolds. The team did not need to make any adjustments during the approach and felt more confident than tense as the window closed on their ability to send commands to the spacecraft. As Adams said, “we had contingencies planned, but we didn’t have to do them.”

One minor fact that emerged is that significant hydrazine and xenon propellant was still on board when it struck, which could affect the ejection of debris from the surface.