A review by the Federal Reserve watchdog found that the transactions of two top officials in 2019 and 2020, when the central bank was mainly active in financial markets, violated neither the law nor central bank policy.

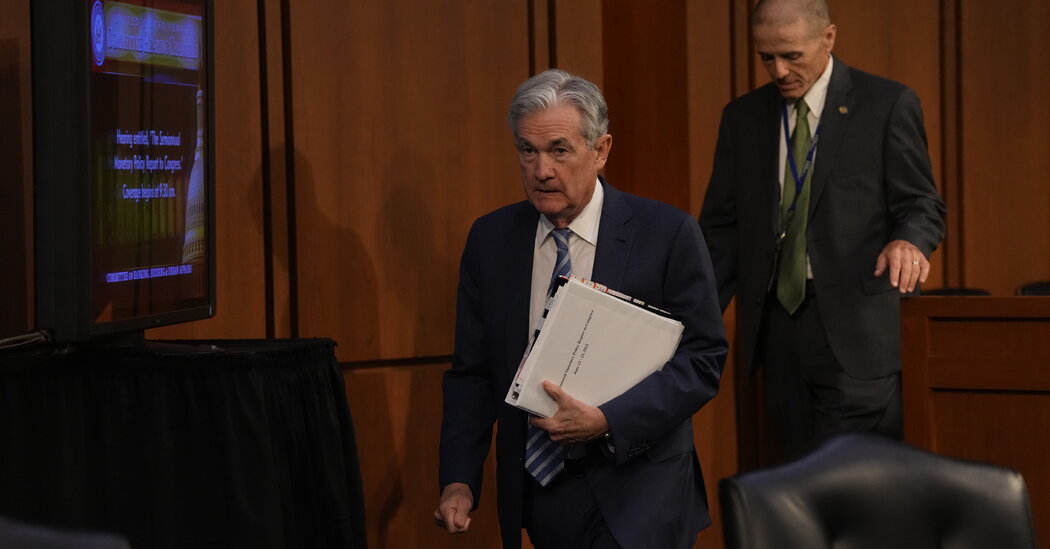

The report of the Inspector General’s Office, released Thursday, acquitted both Chairman Jerome H. Powell and Richard Clarida, the former vice chairman. Both had engaged in transactions that became the subject of media coverage, and in Mr Clarida’s case, this sparked wider criticism from lawmakers and ethics experts.

But the report doesn’t settle what happened to transactions in 2020 conducted by Robert S. Kaplan, former president of the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas, and Eric Rosengren, who was the president of the Federal Reserve Bank of Boston. Both men resigned after their financial dealings became the subject of intense media coverage, with Mr Rosengren citing health reasons for his departure.

“The investigation into senior Reserve Bank officials is ongoing,” the report said.

Still, the first phase of the investigation into a trade scandal that rocked the usually staid central bank and prompted a sweeping ethical reform has ended, good news for the Fed. Mr. Powell and Mr. Clarida’s trade “does not violate any laws, rules, regulations or policies as investigated by our firm,” the report said.

The state of the stock market

The stock market decline this year was painful. And it remains difficult to predict what the future will bring.

In particular, Mr. Clarida was under scrutiny for a series of transactions that took place in early 2020 as the Fed prepared its early response to a coronavirus pandemic. He sold out a stock index on Feb. 24 and bought back into the stock index a few days later, just before an announcement by the Fed that pushed stock prices higher. He didn’t announce the first sale from the stock index until late, after his other trades were investigated.

The watchdog’s review — which included interviews with relevant people and an investigation of emails and other records — noted the omission but found that the transactions themselves did not break any rules.

The report does not specify why Mr. Clarida got out of stock and back into it within days, at a time of intense volatility, while Wall Street kept a close eye on the Fed’s actions. Mr. Clarida’s representative, Tony Fratto, said during a conversation with reporters that Mr. Clarida had sold the equity fund to “create liquidity.” However, when the markets seemed to stabilize, he decided it would be better to return to the equity fund.

Clarida’s buyback of the equity fund took place on February 27. A day later, the central bank released a statement making it clear that it was willing to help the markets in turmoil, which briefly reassured nervous investors, even though the shares were eventually closed for the day. Mr. Fratto said that Mr. Clarida was not aware of the February 28 statement when he made the decision to buy back the fund the previous day.

“He wasn’t trading on inside information – that’s exactly what they were looking for,” said Mr. Fratto on the watchdog report.

Mr Clarida’s resignation came earlier than had been announced, and shortly after news of his February 24 stock fund sale surfaced, casting doubt on his initial explanation of the February 27 move as part of a rebalancing. Mr. Fratto said Mr. Clarida’s decision to leave was based on the timing of the start of the semester at Columbia University, where he would begin teaching, and that he had nothing to do with the transactions.

Neither the Fed nor Mr Clarida gave a reason for his somewhat early departure at the time.

Mr Powell’s trades, as of 2019, were less startling and were also approved by the Fed watchdog.

A financial adviser to Mr. Powell’s family trust conducted transactions in December 2019 during the Fed blackout period — when officials are not expected to act — in December 2019. The report found those transactions were an accident: the woman of Mr. Powell attempted cash a charitable donation, the timing of the transaction intended for that purpose was a mistake on the part of the advisor, and Mr. Powell’s wife was unaware that it had happened during the blackout period.

“With Powell’s stuff, I was very pleased with both the conclusion and the description of what happened,” Kaleb Nygaard, a researcher with the Yale Financial Stability Program, said in response to the report. But he said the explanation of Mr. Clarida’s omissions and transactions was not satisfactory.

“That’s certainly not enough of the story,” he said.