Graphene is the thinnest material known to date and consists of a single layer of carbon atoms arranged in a hexagonal lattice. That structure gives it many unusual properties that hold promise for real-world applications: batteries, supercapacitors, antennas, water filters, transistors, solar cells and touchscreens, to name a few. The physicists who first synthesized graphene in the laboratory won the 2010 Nobel Prize in Physics. But 19th-century inventor Thomas Edison may have unknowingly created graphene as a byproduct of his original experiments with incandescent light bulbs over a century earlier, according to a new paper published in the journal ACS Nano.

“It's very exciting to reproduce what Thomas Edison did, with the tools and knowledge we have now,” said co-author James Tour, a chemist at Rice University. “The discovery that he could have produced graphene sparks curiosity about what other information lies hidden in historical experiments. What questions would our scientific ancestors ask if they could come work with us in the lab today? What questions can we answer if we revisit their work through a modern lens?”

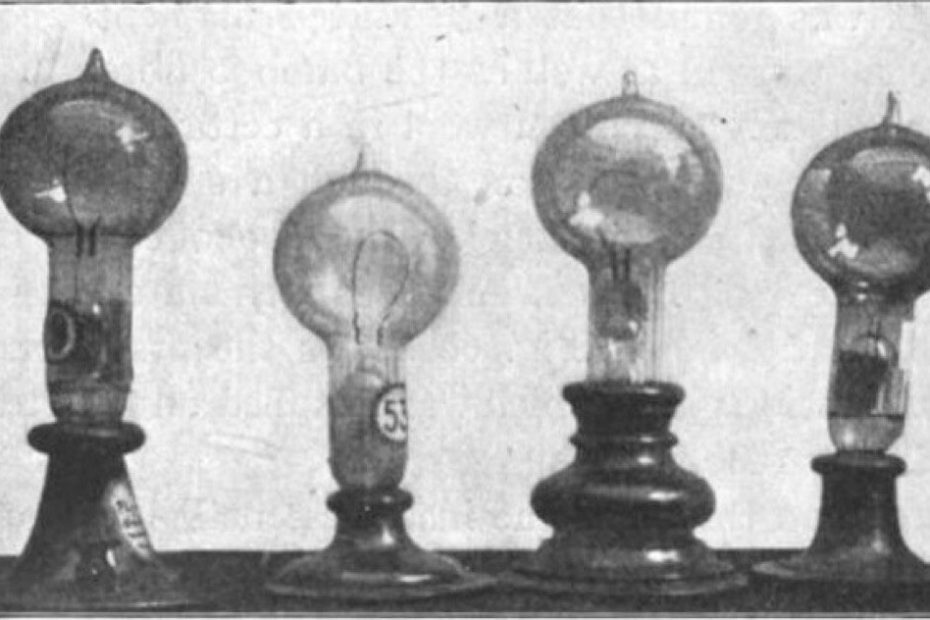

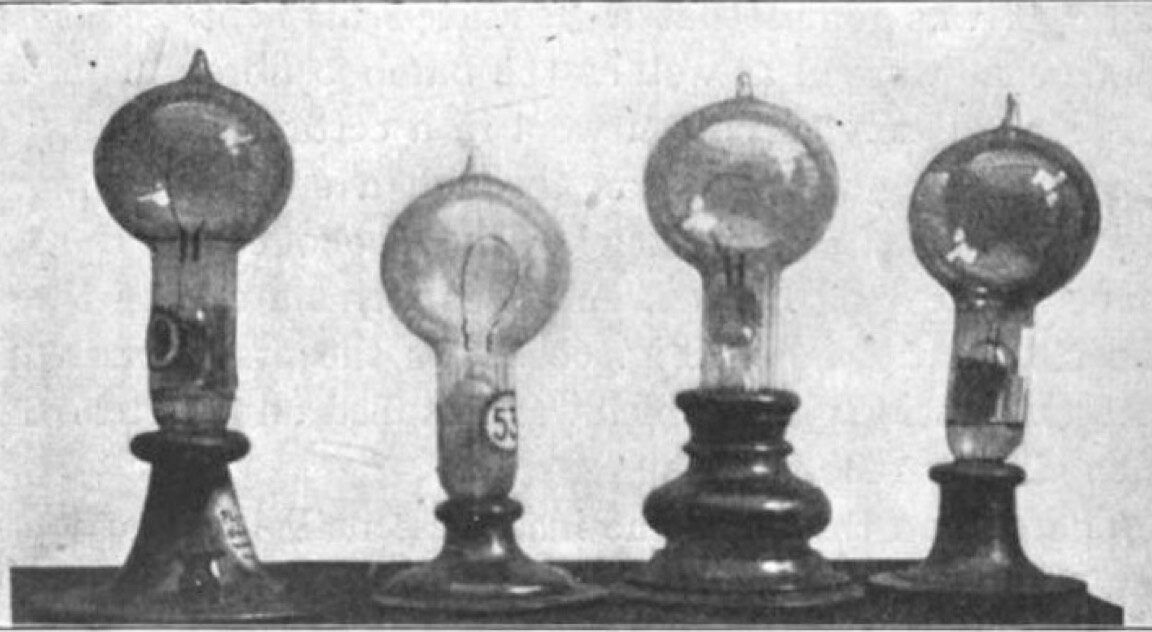

Edison did not invent the concept of light bulbs; there were several versions that predated his efforts. However, they generally had a very short lifespan and required high electrical current, so they did not fit well with Edison's vision of large-scale commercialization. He experimented with different filament materials, starting with carbonized cardboard and pressed lamp black. This also burned out quickly, as did filaments made with various grasses and sticks, such as hemp and palmetto. Ultimately, Edison discovered that carbonized bamboo produces the best filament, with a lifespan of more than 1,200 hours when using a 110-volt power source.

Lucas Eddy, Tour's graduate student at Rice, tried to find ways to mass produce graphene using the smallest, easiest equipment he could manage, with materials that were both affordable and readily available. He considered options like arc welders and natural phenomena like lightning striking trees – both of which he admitted were “complete dead ends.” Edison's incandescent bulb, Eddy decided, would be ideal because Edison's version, unlike other early incandescent bulbs, could reach the critical temperatures of 2,000 degrees Celsius needed for flash-joule heating – the best method for making so-called turbostratic graphene.