One is striking about the spectrum of use for artificial intelligence.

The large, inspiring AI opportunity on the horizon, experts agree, lies in accelerating and transforming scientific discovery and development. Fueled by huge points of scientific data, AI promises to generate new medicines to combat diseases, new agriculture to feed world population and new materials to unlock green energy – all in a small fraction of the time of traditional research.

Technology companies such as Microsoft and Google make AI tools for science and work together with partners in areas such as Drug Discovery. And last year the Nobel Prize in Chemistry went to scientists who used AI to predict and make proteins.

This month, Lila Sciences became public with his own ambitions to revolutionize science via AI, the start-up, which is located in Cambridge, Massachusetts, had worked secretly for two years “to build scientific super intelligence to resolve the biggest challenges of humanity.”

Based on an experienced team of scientists and $ 200 million in initial financing, Lila has developed an AI program that has been trained from published and experimental data, as well as the scientific process and the reasoning. The start-up then lets AI software carry out experiments in automated, physical laboratories with a few scientists to help.

In projects that demonstrate technology, Lila's AI has already generated new antibodies to combat diseases and developed new materials for catching carbon from the atmosphere. Lila changed those experiments within a few months to physical results in his laboratory, a process that would probably take years with conventional research.

Experiments such as Lila have convinced many scientists that AI will soon make the hypothesis experiment test cycle faster than ever. In some cases, AI could even exceed the human imagination with inventions, the progress of turbula veins.

“AI will have the next revolution of this most valuable thing that people ever encountered – the scientific method,” said Geoffrey von Maltzahn, Chief Executive of Lila, who a Ph.D. In Biomedical Engineering and Medical Physics of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

The push to reinvent the scientific discovery process builds on the power of generative AI, which burst into public consciousness a little more than two years ago with the introduction of OpenAi's Chatgpt. The new technology is trained on data on the internet and can answer questions, write reports and compile e -mail with human fluency.

The new breed of AI caused a commercial arms race and apparently unlimited editions by technology companies, including OpenAI, Microsoft and Google.

(The New York Times has sued OpenAi and Microsoft, who formed a partnership, accused them of infringing copyright with regard to news content with regard to AI systems. OpenAi and Microsoft have denied those claims.)

Lila has followed a science -oriented approach to train its generative AI, feeding research documents, documented experiments and data from his fast -growing Life Science and Materials Science Lab. According to the Lila team, that is the technology both depth in science and the broad skills, whereby the way in which Chatbots can write poetry and computer code can reflect.

Yet Lila and every company that work on cracking “scientific super intelligence” will say scientists for major challenges. Although AI already brings about a revolution in certain fields, including discovering medicines, it is unclear whether the technology is only a powerful tool or on a path to matching or surpassing all human skills.

Since Lila works in secret, scientists from outside are unable to evaluate his work and, according to them, early progress in science does not guarantee success, because unforeseen obstacles often come up later.

“More power for them, if they can,” said David Baker, a biochemist and director of the Institute for Protein Design at the University of Washington. “It seems beyond everything I know in scientific discovery.”

Dr. Baker, who shared the Nobel Prize for Chemistry last year, said he saw AI more as a tool.

Lila was interpreted in flagship pioneers, an investor in and productive maker of biotechnology companies, including the COVID-19maker Moderna. Flagship carries out scientific research, aimed at where breakthroughs are likely to be within a few years and can be commercially valuable, said Noubar Afeyan, founder and chief executive of the flagship.

“So we don't just care about the idea, we care about the timeliness of the idea,” said Dr. Afeyan.

Lila resulted from the merger of two early AI business projects in the flagship, one was aimed at new materials and the other on biology. The two groups tried to solve similar problems and recruit the same people, so they combined forces, said Molly Gibson, a computational biologist and a Lila-Mede founder.

The Lila team has completed five projects to demonstrate the possibilities of its AI, a powerful version of one of a growing number of advanced assistants known as agents. In any case, scientists – who usually had no specialty in the subject – typed a request to reach the AI program. After refining the request, the scientists, who worked with AI as a partner, carried out experiments and tested the results – time and time again, steadily at home at the desired target.

One of those projects found a new catalyst for the production of green hydrogen, where electricity is used to split water into hydrogen and oxygen. The AI was instructed that the catalyst had to be abundant or easy to produce, in contrast to Iridium, the current commercial standard. With the help of AI, the two scientists found a new catalyst in four months – a process that can usually take years.

That success helped John Gregoire, a prominent researcher in new materials for Clean Energy, to persuade to leave the California Institute of Technology last year to join Lila as head of physical sciences.

George Church, a geneticist of Harvard, known for his groundbreaking research into genome senequencing and DNA synthesis that has been founded dozens of companies, also recently became a member of Lila's Chief Scientist.

“I think science is really a good subject for AI,” said Dr. Church. Science is aimed at specific knowledge areas, where truth and accuracy can be tested and measured, he added. In science, this makes AI less susceptible to the wandering and incorrect answers, known as hallucinations, sometimes made by chatbots.

The early projects are still far away from market -ready products. Lila will now collaborate with partners to commercialize the ideas that come from the laboratory.

Lila is expanding its laboratory room in a flagship building with six floors in Cambridge, next to the Charles River. In the next two years, Lila says, it is planning to go to a separate building, add tens of thousands of square foot laboratory space and open offices in San Francisco and London.

On a recent day, trays with 96 wells from DNA samples drove on magnetic traces, whereby the directions quickly shift for delivery to various laboratory stations, depending on what the AI suggested. The technology seemed to improvise when the experimental steps carried out in the pursuit of new proteins, gene itors or metabolic routes.

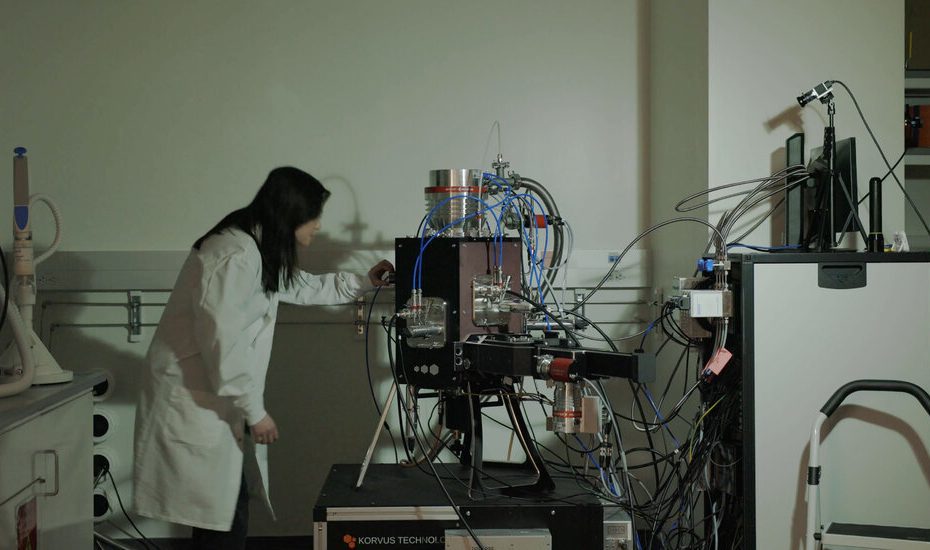

In another part of the laboratory, scientists used high-tech machines that are used to make, measure and analyze adapted nanoparticles of new materials.

The activity on the laboratory floor was led by a collaboration of white -coated scientists, automated equipment and unseen software. Every measurement, every experiment, every incremental success and failure was recorded digitally and introduced in Lila's AI, so that it constantly learns, becomes smarter and does more in itself.

“Our goal is really to give AI access to perform the scientific method – to come up with new ideas and actually go into the lab and test those ideas,” Dr. Gibson.