“If the island sinks, I will sink with it,” says Delfino Davies, his smile does not fade for a second.

There is silence, apart from the swish of his broom over the floor of the small museum that he runs the life of his community in Panama, the Guna.

“You used to hear children scream … Everywhere music, neighbors argue,” he says, “but now all the sounds have disappeared.”

His community, which lives on the small low -lying island of Gardi Sugdub, is the first in Panama to be moved due to climate change.

The government has said that with “threatening risk” they are confronted by rising sea level, of which scientists say they will probably make the island uninhabitable by 2050.

Delfino says that many of his family and friends have left the island [BBC]

In June last year, most residents left this tight Wirwar van Houten and Tinwoningen for rows neatly prefabricated houses on the mainland.

The move is praised by some as a model for other groups worldwide whose houses are threatened, but it has nevertheless divided the community.

“My father, my brother, my sister -in -law and my friends are gone,” says Delfino. “Sometimes the children whose families have stayed wonder where their friends have gone, he says.

House after house is a padlock. About 1,000 people left, while about 100 remained – some because there was not enough room in the new settlement. Others, such as Delfino, are not fully convinced that climate change is a threat, or just did not want to leave.

He says he wants to stay close to the ocean where he can fish. “The people who lose their tradition lose their souls. The essence of our culture is on the islands,” he adds.

Isberyala, the new settlement, is 15 minutes by boat and then a five -minute drive from the island of Gardi Sugdub [BBC]

The Guna has been living on Gardi Sugdub since the 19th century, and even longer on other islands in this archipelago for the north coast of Panama. They fled from the mainland to escape from Spanish conquerors and, later, epidemics and conflict with other indigenous groups.

They are known for their clothing called “Molas”, decorated with colorful designs.

The Guna currently occupies more than 40 other islands. Steve Paton, a scientist at the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute in Panama, says that it is “almost a certainty” that most, if not all of the islands are immersed before the end of the century.

Because climate change ensures that the earth warms up, the sea level rise as glaciers and ice caps melt and sea water extends as it warms up.

Scientists warn that hundreds of millions of people who live in coastal areas all over the world can be endangered by the end of the century.

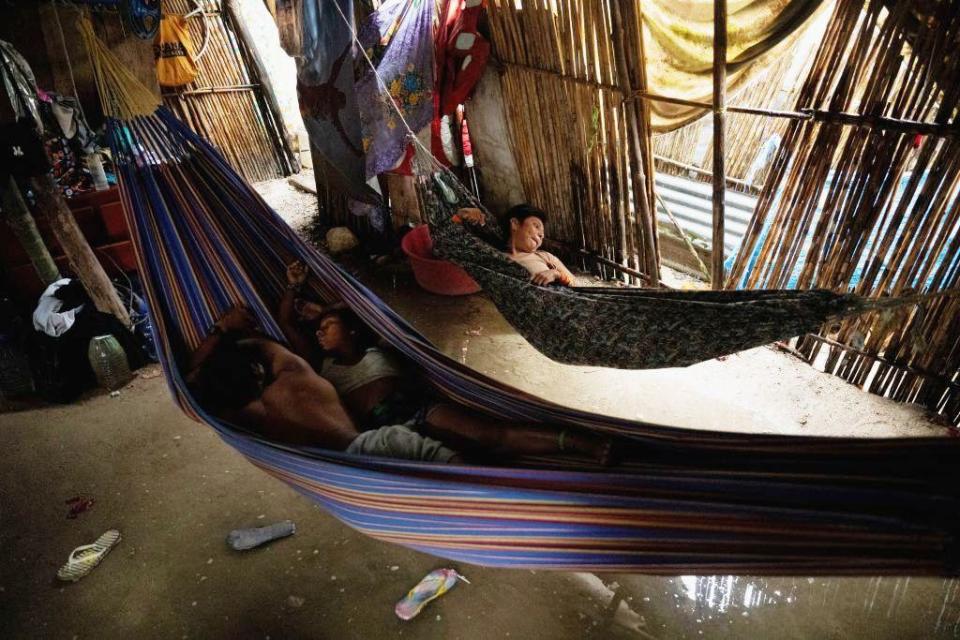

Water had entered this house under the hammocks, just before the move took place in June 2024 [Getty Images]

On Gardi Sugdub, waves are waved during the rainy season in Huizen in Huizen and pieces under the hammocks where families sleep.

Mr. Paton says: “It is very unlikely that the island will be habitable by 2050, based on the current and expected speed of the sea level rise”.

However, the first discussions about relocation started more than ten years ago, due to the population growth, not on climate change.

The island is only 400 meters long and 150 meters wide. Some residents see overpopulation as the more urgent problem. But others, such as Magdalena Martínez, fear the rising sea:

“Every year we saw that the tides were higher,” she says. “We couldn't cook on our stoves and it was always flooded … So we said,” We have to leave here “.”

Magdalena was one of those who scramble in motor boats and wooden canoes last June, on the way to new houses.

“I only brought my clothes and some kitchen utensils,” she says. “You feel that you are leaving pieces of your life on the island.”

“You miss your friends, the streets where you lived, being so close to the sea,” says Magdalena [BBC]

The new community, Isberyala, is – the weather that allows – only 15 minutes by boat, followed by a five -minute drive from Gardi Sugdub. But it feels like another world.

Identic white and yellow houses line asphalted roads.

Magdalena's eyes light up while she shows off the “small house” where she lives with her 14-year-old granddaughter Bianca and her dog.

Every house has a small area behind it – a luxury that is not available on the island. “I want to plant Yucca, tomatoes, bananas, mangos and pineapple,” she is enthusiastic.

“It is pretty sad to leave a place where you have been for so long. You miss your friends, the streets where you live, so close to the sea,” she says.

[BBC]

Isberyala was built with $ 15 million (£ 12 million) from the Panamanian government and extra financing of the Inter-American Development Bank.

In his new meeting house, that is with branches and leaves in the traditional style, Tito López, Sayla or leader of the community awaits.

“My identity and my culture will not change, it is only the houses that have changed,” he says.

He lies in a hammock and explains that as long as the hammock holds its place in the Guna culture, “the heart of the Guna people will live”.

When a Guna dies, they are in their hammock for family and friends for a day to visit. It is then buried next to them.

The school teaches its students traditional music and dance to help maintain the Guna culture [BBC]

In the state-of-the-art new school, students aged 12 and 13 rehearses Guna music and dancing. Boys in clear shirts play panpipes, while girls wearing Molas shaking Maracas.

The tight school on the island is now closed and students whose families stayed there, travel every day to the new building with its computers, sports fields and library.

Magdalena says that the conditions in Isberyala are better than on the island, where she says they only had four hours of electricity a day and had to get drinking water by boat from a river on the mainland.

In Isberyala the power supply is constant, but the water – pumped from Putten nearby – is only hired a few hours a day. The system was sometimes demolished for days in a row.

Isberyala's leader Tito López says that his identity and culture will not change in the new settlement [BBC]

There is also no health care yet. Another resident, Yanisela Vallarino, says that her young daughter was unwell one evening and that she had to arrange transport to the island late in the evening to visit a doctor.

The Panamanian authorities told the BBC that the construction of a hospital in Isberyala got stuck ten years ago due to a lack of financing. But they said they hoped to breathe new life into the plan this year and were assessing how they could create space for remaining residents to move from the island.

Overpopulation had become a problem on Gardi Sugdub, where houses up to and including the water are built [Getty Images]

Yanisela is pleased that she is now able to take evening lessons in the new school, but she still often returns to the island.

“I am not used to it yet. And I miss my house,” she says.

Communities around the world will be “inspired” by the way in which the inhabitants of Gardi Sugdub have confronted their situation, says Erica Bower, a researcher in the field of climate displacement at Human Rights Watch.

“We must learn from these early cases to understand how success even looks,” she says.

Yanisela still often visits the island and says she is missing her old house [BBC]

While the afternoon arrives, the school activities make way for the screams and coil about football, basketball and volleyball.

“I prefer this place above the island because we have more room to play,” says eight -year -old Jerson, before we dive for a football.

Magdalena sits with her granddaughter and learns to sew her molas.

“It's hard for her, but I know she's going to learn. Our unique ways cannot be lost,” says Magdalena.

Asked what she is missing about the island, she replies: “I wish we were all there.”