Scientists are fairly certain that Europa has water, perhaps twice as much as the water in all of the Earth's oceans. Jupiter's strong gravitational field continually pulls on Europa as it orbits its parent planet every three and a half days, squeezing and bending the moon's interior and generating heat through tidal forces. These forces could power hydrothermal vents where the floor of the European ocean meets the moon's rocky interior.

This is what separates Europa, Earth and Saturn's small moon Enceladus — which also has a hidden ocean and erupting plumes — from every other object in the solar system, according to Cynthia Phillips, planetary geologist and Europa Clipper project staff scientist at JPL.

“In these worlds you have an ocean layer on top of a rock layer,” she said. “That's important because that's what we have here on Earth, and at the bottom of the Earth's oceans, where that ocean layer meets the rocks. you can have all kinds of interesting chemical reactions happening, and hydrothermal systems.”

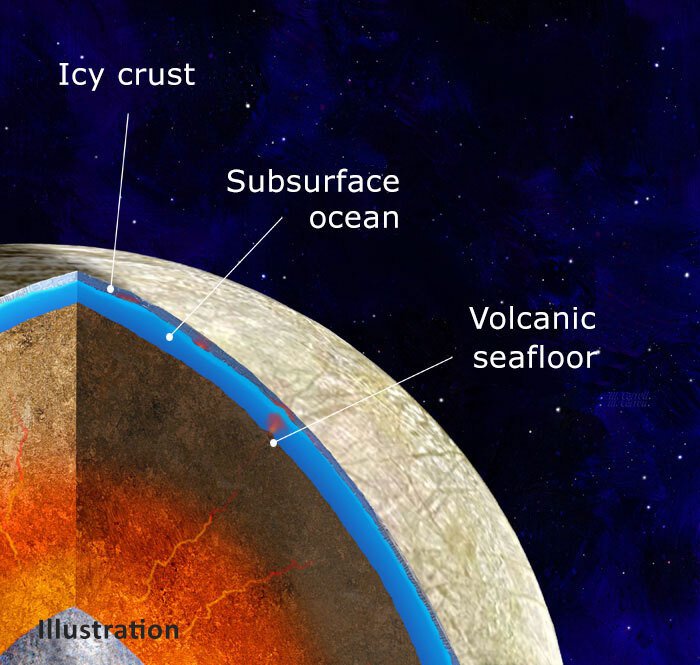

Scientists' findings suggest that the interior of Jupiter's moon Europa may consist of an iron core surrounded by a rocky mantle that is in direct contact with an ocean beneath the icy crust. New research models how internal heat can fuel seafloor volcanoes.

Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/Michael Carroll

Scientists' findings suggest that the interior of Jupiter's moon Europa may consist of an iron core surrounded by a rocky mantle that is in direct contact with an ocean beneath the icy crust. New research models how internal heat can fuel seafloor volcanoes.

Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/Michael Carroll

At the bottom of Earth's oceans, such as in Europe, organisms depend on an energy source other than the sun. Hydrothermal vents in Earth's oceans provide a heated environment teeming with primitive life forms, even in harsh conditions several kilometers deep.

“We don't expect those kinds of fish and whales, but we are interested in whether Europa could support simple life: single-celled organisms,” Pappalardo said.

Of course, Europa Clipper won't be able to dig tens of kilometers to reach these theoretical vents. Scientists will have to infer their presence from other data. And direct detection of any living organism on Europa will have to wait for a future mission. Scientists don't think life could survive on Europa's surface because it is bathed in the extreme radiation of Jupiter's magnetosphere.

“If there is life on Europa, in this habitable environment we're investigating, it would be under the ocean, so we wouldn't be able to see it,” Buratti said. “We're looking for chemicals on the surface, organic chemicals that are the precursors of life. There are dream things we could see, like DNA or RNA, but we don't expect to see them.”