Next month marks the 10th anniversary of NASA’s announcement that Boeing, one of the agency’s most experienced contractors, had won the lion’s share of available government funding, freeing the agency from its reliance on Russia to ferry its astronauts to and from low Earth orbit.

Boeing was awarded $4.2 billion by NASA at the time to complete development of the Starliner spacecraft and conduct at least two, and possibly up to six, operational crew flights to rotate crews between Earth and the International Space Station (ISS). SpaceX won a $2.6 billion contract for essentially the same scope of work.

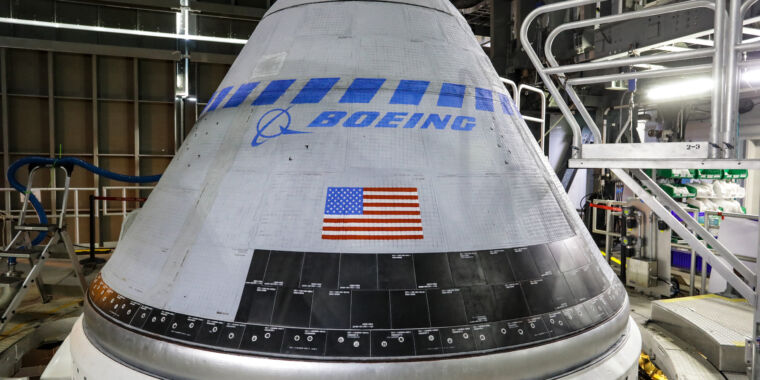

A decade later, the Starliner program is at a crossroads after Boeing learned it would not complete the spacecraft’s first Crew Flight Test with astronauts aboard. NASA formally decided Saturday that Butch Wilmore and Suni Williams, who launched aboard the Starliner capsule on June 5, will instead return to Earth aboard a SpaceX Crew Dragon spacecraft. Simply put, NASA doesn’t have enough confidence in Boeing’s spacecraft after it repeatedly suffered from thruster failures and helium leaks en route to the ISS.

So where does this leave Boeing with its multibillion-dollar contract? Can the company meet the breadth of its commercial crew contract with NASA before the space station’s planned retirement in 2030? It now appears unlikely that Boeing will fly six more Starliner missions without an extension of the ISS’s lifespan. Perhaps tellingly, NASA has only placed firm orders with Boeing for three Starliner flights once the agency certifies the spacecraft for operational use.

Boeing's profit margin

While Boeing made no official statement Saturday about its long-term plans for Starliner, NASA Administrator Bill Nelson told reporters that he had received assurances from Boeing’s new CEO, Kelly Ortberg, that the company remains committed to the commercial crew program. And it will take a significant commitment from Boeing to pull it off. Under the terms of its fixed-price contract with NASA, the company is responsible for paying all costs to fix the booster and helium leak problems and get Starliner flying again.

Boeing has already reported $1.6 billion in costs in its financial statements to pay for delays and cost overruns on the Starliner program. That amount will increase because the company will likely have to redesign several elements of the spacecraft’s propulsion system to fix problems encountered during the Crew Flight Test (CFT) mission. NASA has committed $5.1 billion to Boeing for the Starliner program, and the agency has already disbursed most of that funding.

The next step for Starliner remains unclear, and we’ll assess that in more detail later in the story. If the Starliner test flight had ended as expected, with the crew inside, NASA had scheduled Boeing to launch the first of its six operational crew rotation missions to the space station no earlier than August 2025. Given Saturday’s decision, it’s likely Starliner won’t fly with astronauts again until at least 2026.

Starliner safely delivered astronauts Butch Wilmore and Suni Williams to the space station on June 6, a day after their launch from Cape Canaveral Space Force Station, Florida. But five of the craft's 28 reaction control system thrusters overheated and failed as it approached the orbiting outpost. After the failures en route to the space station, NASA engineers were concerned that Starliner would suffer similar problems, or worse, when its control jets were fired to guide Starliner on its journey back to Earth.

On Saturday, NASA officials decided it wasn’t worth the risk. The two astronauts, originally scheduled to stay on the space station for eight days, will now spend eight months in the research lab in space before returning to Earth with SpaceX.

If it's not a trust issue, is it a judgment issue?

Boeing executives had previously said that Starliner was safe enough to take Wilmore and Williams home. Mark Nappi, Boeing's Starliner program manager, appeared to frequently downplay the severity of the booster's problems during press conferences during Starliner's nearly three-month mission.

Why did NASA and Boeing engineers come to different conclusions? “I think we look at the data and the data and the uncertainty that's out there differently than Boeing does,” said Jim Free, NASA's associate administrator and the agency's top official. “It's not a question of confidence. It's our technical expertise and our experience that we have to balance. We balance risk across everything, not just Starliner.”

The people at the top of NASA's decision-making tree have either flown in space before or had a front-row seat to NASA's disastrous decision in 2003 not to request further data on the condition of the space shuttle. Colombia'left wing after impact with a foam block from the shuttle fuel tank during launch, resulting in the deaths of seven astronauts and the destruction of Colombia during reentry over East Texas. A similar normalization of technical problems and a culture of oppressive dissent led to the loss of the space shuttle Challenger from 1986.

“We lost two space shuttles because there was no culture of coming forward,” Nelson said Saturday. “We've made it very clear to all of our employees: If you have an objection, come forward. Space flight is risky, even at its safest and most routine. And a test flight, by its very nature, is neither safe nor routine. So the decision to keep Butch and Suni on the International Space Station and to bring Starliner home unmanned is the result of a commitment to safety.”

Now it appears that the culture has really changed. With SpaceX’s Dragon spacecraft capable of bringing Wilmore and Williams home, it turned out to be a relatively easy decision. Ken Bowersox, head of NASA’s Space Mission Directorate, said that managers polled for their opinions were all in favor of returning the Starliner spacecraft to Earth with no one on board.

NASA and Boeing, however, must answer the question of how the Starliner program got to this point. The space agency approved the launch of the Starliner CFT mission in June despite knowing that the spacecraft had a helium leak in its propulsion system. Those leaks multiplied once Starliner arrived in orbit, and are a serious problem in their own right that requires corrective action before the next flight. Ultimately, the problems with the booster rocket trumped the seriousness of the helium leaks, and this is where NASA and Boeing will likely face the toughest questions going forward.

Boeing’s previous Starliner mission, known as Orbital Flight Test-2 (OFT-2), successfully launched and docked with the space station in 2022, later returning to Earth for a parachute-assisted landing in New Mexico. The test flight accomplished all of its major objectives, setting the stage for this year’s Crew Flight Test mission. However, the spacecraft was plagued by booster problems on that flight as well.

Several of the reaction control system thrusters stopped working as Starliner approached the space station during the OFT-2 mission, and another failed during the mission's return trip. Engineers thought they had solved the problem by introducing what was essentially a software fix to adjust the timing and tolerance settings on sensors in the propulsion system, supplied by Aerojet Rocketdyne.

That didn’t work. The problem lay elsewhere, as engineers discovered during tests this summer, when Starliner was already in orbit. Thrusters at White Stands, New Mexico, revealed that a small Teflon seal in a valve can bulge when overheated, restricting the flow of oxidizer to the booster. NASA officials concluded that there was a chance, however remote, that the thrusters could overheat again as Starliner leaves the space station and flies back to Earth, or perhaps get worse.

“We're clearly operating this thruster at a higher temperature, at times, than it's designed for,” said Steve Stich, NASA's commercial crew program manager. “I think that was a factor, that when we started looking at the data a little bit more closely, we were operating the thruster outside of its normal operating range.”