More than 200 kilometres off the coast of Norway in the North Sea is the world's first offshore carbon capture and storage project. Built in 1996, the Sleipner project extracts carbon dioxide from natural gas, which is largely methane, to make it marketable. But instead of the CO2 The greenhouse gas is stored in the atmosphere.

The effort will save about 1 million tons of CO2 per year – and is being hailed by many as a groundbreaking success in global efforts to reduce greenhouse gas emissions.

Last year, total global CO2 emissions reached a record high of about 35.8 billion tons, or gigatons. At these levels, scientists estimate we have about six years left before we emit that much CO22 that global warming will consistently exceed 1.5° Celsius above average pre-industrial temperatures, an internationally agreed limit. (Notably, the average global temperature has exceeded this threshold over the past 12 months.)

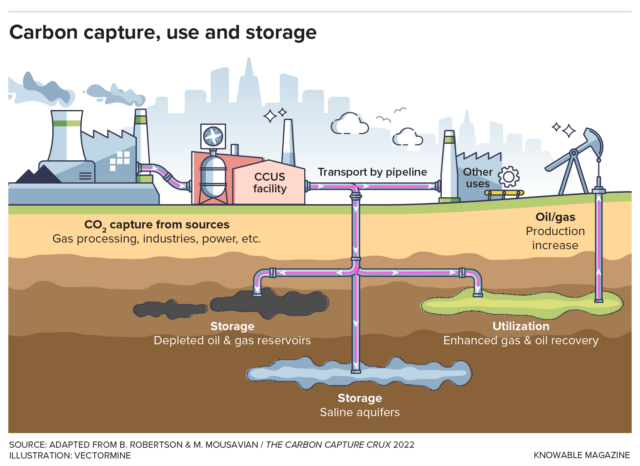

Phasing out fossil fuels is essential to reducing emissions and combating climate change. But a suite of technologies collectively known as carbon capture, utilization and storage, or CCUS, are among the tools available to meet global carbon reduction goals.2 to halve emissions by 2030 and achieve net zero emissions by 2050. These technologies capture, use or store CO2 emitted from power generation or industrial processes, or suck it directly out of the air. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), the United Nations body charged with assessing climate change science, counts carbon capture and storage among the actions needed to reduce emissions and meet temperature goals.

Governments and industry are betting big on such projects. Last year, for example, the UK government announced £20 billion (more than $25 billion) in funding for CCUS, often abbreviated as CCS. The United States has committed more than $5 billion between 2011 and 2023, and has pledged another $8.2 billion from 2022 to 2026. Globally, public funding for CCUS projects is set to rise to $20 billion by 2023, according to the International Energy Agency (IEA), which works with countries around the world to shape energy policy.

Given the urgency of the situation, many argue that CCUS is necessary to move society toward climate goals. But critics don't see the technology, in its current form, as moving the world away from oil and gas: in many cases, they point out, the captured CO2 is used to extract more fossil fuels in a process known as enhanced oil recovery. They argue that other existing solutions such as renewable energy offer deeper and faster carbon emissions2 emissions reductions. “It’s better to not emit at all,” says Grant Hauber, an energy finance consultant at the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis, an independent organization in Lakewood, Ohio.

Furthermore, fossil fuel companies provide money to universities and researchers, which some say can sway what gets studied and what doesn’t, even if the work of individual scientists is legitimate. For these reasons, some critics say CCUS shouldn’t be pursued at all.

“Carbon capture and storage essentially perpetuates dependence on fossil fuels. It’s a distraction and delay tactic,” says Jennie Stephens, a climate justice researcher at Northeastern University in Boston. She adds that there’s been little attention paid to understanding the psychological, social, economic and political barriers that keep communities from transitioning away from fossil fuels and forging solutions to those obstacles.

According to the Global CCS Institute, an industry-led think tank headquartered in Melbourne, Australia, the 41 commercial projects operating as of July 2023 were largely part of efforts that produce, extract or burn fossil fuels, such as coal- and gas-fired power plants. That includes the Sleipner project, run by energy company Equinor. That includes the world’s largest CCUS facility, operated by ExxonMobil in Wyoming, in the United States, which also captures carbon.2 as part of the production of methane.

Granted, not all CCUS efforts promote fossil fuel production, and many projects now in the works have the sole purpose of capturing and storing CO2Yet some critics doubt whether these greener approaches can ever capture enough carbon.2 to make a meaningful contribution to limiting climate change, and they are concerned about the costs.

Others are more cautious. Sally Benson, an energy researcher at Stanford University, doesn't want CCUS to be used as an excuse to continue with fossil fuels. But she says the technology is essential for capturing some of the CO2 of fossil fuel production and use, and of industrial processes, as society shifts to new energy sources. “If we can eliminate those emissions with carbon capture and storage, that sounds like success to me,” said Benson, who co-directs an institute that receives funding from fossil fuel companies.