Sign up for CNN's Wonder Theory science newsletter. Explore the universe with news about fascinating discoveries, scientific developments and more.

Denisovans survived and thrived on the high Tibetan Plateau for more than 100,000 years, according to a new study. The research advances scientific knowledge about the enigmatic ancient humans first identified in 2010.

Researchers analyzed thousands of animal bone fragments excavated from the Baishiya Karst Cave, 3,280 meters above sea level near the city of Xiahe in China’s Gansu province — one of only three sites where extinct humans are known to have lived. Their work revealed that Denisovans could hunt, butcher and process a variety of different animals large and small, including woolly rhinoceroses, blue sheep, wild yaks, marmots and birds.

The team of archaeologists working in the cave also discovered a fragment of a rib bone in a layer of sediment that dates to between 48,000 and 32,000 years ago, making it the youngest of the handful of known Denisovan fossils, suggesting the species was around longer than scientists previously thought.

Due to a lack of fossil evidence, details about how these archaic human ancestors lived are scarce. But the new study reveals that Denisovans living in Baishiya Karst Cave were incredibly resilient, surviving in one of the most extreme environments on Earth through hotter and colder periods and maximizing the diverse animal resources available in the grassland landscape.

“We know that the Denisovans lived in the cave and on this Tibetan plateau for so long, we really want to know how they lived there? How did they adapt to the environment?” said Dongju Zhang, an archaeologist and professor at Lanzhou University in China and co-lead author of the study published Wednesday in the journal Nature.

“They used whatever animals were available to them, which means their behavior is flexible,” Zhang added.

The rib belonged to a Denisovan who likely lived at a time when modern humans were spreading across the Eurasian continent, said study co-author Frido Welker, an associate professor in the Biomolecular Paleoanthropology Group at the Globe Institute at the University of Copenhagen. He said future research at the site and in the region could shed light on whether the two groups interacted there.

“It puts this fossil and the (sediment) layer into a context where we know there were probably people present in the wider region, and that's interesting,” he said.

A trail of Denisovan clues

Denisovans were first identified a little over a decade ago in a lab using DNA sequences extracted from a small fragment of a finger bone. Since then, fewer than a dozen Denisovan fossils have been found worldwide.

Most of these were found in the Denisova Cave in the Altai Mountains of Siberia, from which the group got its name. Genetic analysis subsequently revealed that the Denisovans, like Neanderthals, had once interbred with modern humans. Traces of Denisovan DNA found in modern humans suggest that the ancient species probably once lived across much of Asia.

It wasn't until 2019 that researchers identified the first Denisova fossil outside the cave of the same name.

A jawbone with teeth found by a monk in Baishiya Karst Cave, a sacred site for Tibetan Buddhists, dated back at least 160,000 years and contained a molecular signature of Denisovans. The discovery of DNA from sediment at the site, published a year later, provided more evidence that Denisovans had once called the area home.

In 2022, scientists identified a tooth unearthed in a cave in Laos as a Denisovan, hinting that the species first arrived in Southeast Asia. As with the jaw, no DNA could be extracted from the tooth, so researchers instead studied the microscopic remains of proteins, which are better preserved than DNA but less informative.

The study, published on Wednesday, examined more than 2,500 pieces of animal bone found during excavations at Baishiya Cave in 2018 and 2019.

Most of the fragments were too small to be identified with the naked eye, so the researchers turned to a relatively new technique known as Zooarchaeology by Mass Spectrometry (ZooMS). This allows scientists to extract valuable information from specimens that may have been overlooked in the past.

Based on small differences in the amino acid sequence of collagen preserved in the bone, ZooMS helped the researchers determine what type of animal the bones came from.

Baishiya's place in Denisova's story

In addition to large and small herbivores, the analysis revealed carnivores such as hyenas. Some of the animals, such as the blue sheep, are still common in the Himalayas today.

Many of the bones had cut marks indicating that the Denisovans processed the animals for their hides, as well as meat and bone marrow. Some bones were also used as tools, the study found.

The diversity of animal species found suggests that the area around the cave was dominated by a grassland with some small forest areas – similar to today, although Zhang noted that most of the animals living there today are domesticated yaks and goats.

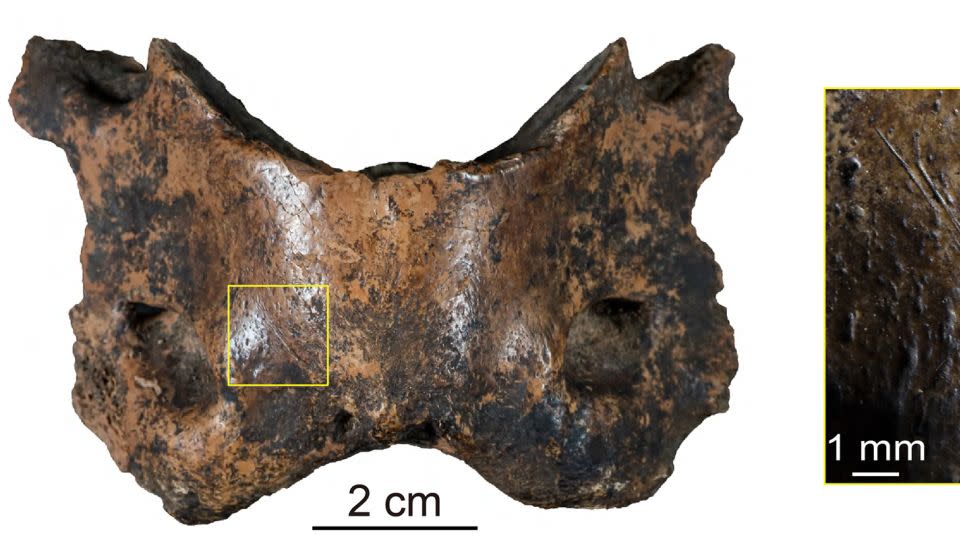

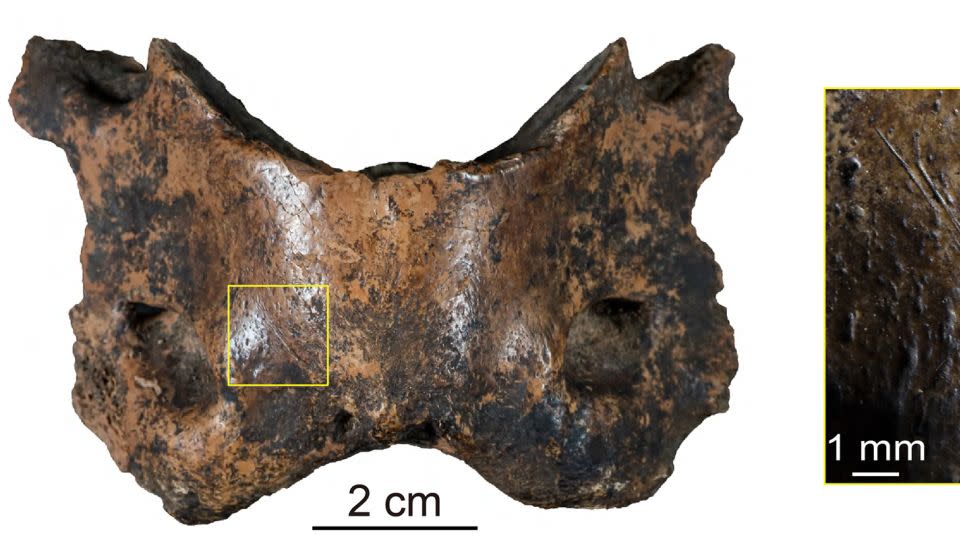

During the painstaking process of categorizing the bones, which took several months, the team identified the rib bone fragment, which is 5 centimeters long. However, the resolution of the protein information was not clear enough to directly determine what kind of human it belonged to. Further analysis of the preserved ancient proteins led by Welker revealed that it was a Denisovan.

The rib bone came from a layer of sediment from which the team had previously extracted Denisovan DNA, and Zhang said the researchers are trying to extract DNA from the new specimen. That process could yield more detailed genetic information about the rib's owner and the broader Denisovan population that once lived in the area.

With so little information about the Denisovans, “every discovery is of great importance” and the zooarchaeological analysis conducted by the authors of the new study was “particularly illuminating,” said archaeologist Samantha Brown, a Junior Group Leader for Palaeoproteomics at Germany’s University of Tübingen who has worked on remains from Denisova Cave.

“The young age of the fossil was absolutely surprising. In this period, we have evidence of modern humans occupying sites all the way to Australia. It really opens up conversations about the possibility that those groups came into contact with each other as modern humans moved into Asia and the Pacific, but more evidence will probably be needed to understand the nature of those interactions,” said Brown, who was not involved in the study.

Work is still ongoing at Baishiya Karst Cave, and Zhang is currently excavating another Paleolithic site in the region that may have been home to Denisovans or modern humans who came after them, she says.

Unlike Denisova Cave, which was inhabited by early modern humans and Neanderthals, as well as Denisovans, current evidence suggests that Denisovans were the only group of people living in Baishiya Karst Cave, Zhang said. That makes the Tibetan Plateau — an area nicknamed “the roof of the world” — a particularly important location in the search for answers to the many remaining questions about who the Denisovans were, what they looked like, how they disappeared and their place on the human family tree.

For more CNN news and newsletters, create an account at CNN.com