Inflation data released on Wednesday showed a pronounced cooling, offering the most hopeful news since the Federal Reserve began taming rapid price increases 16 months ago.

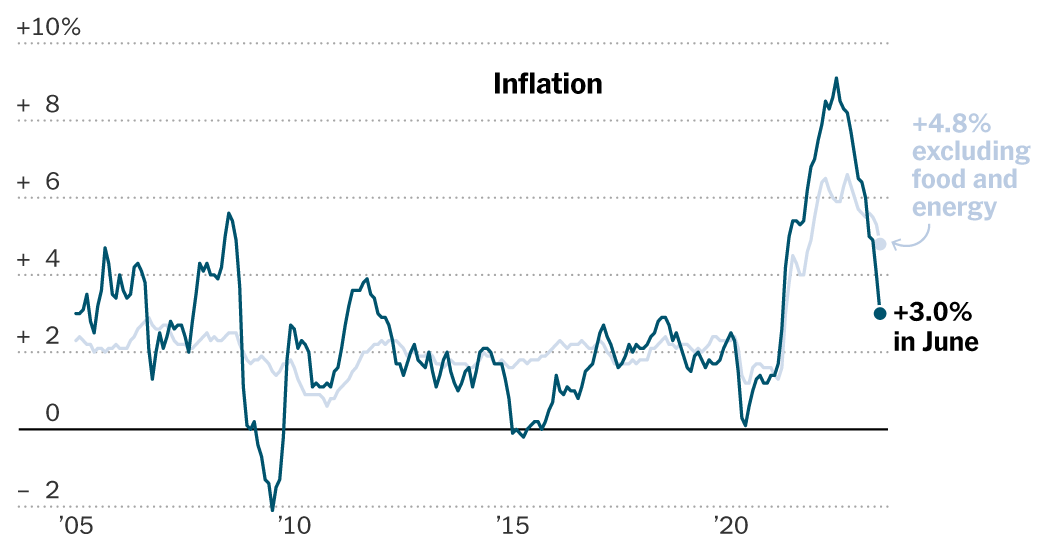

The consumer price index climbed 3 percent in the year to June, less than the 4 percent increase in the year to May and only a third of its peak of about 9 percent last summer.

That overall measure captures major drops in gas prices and a few other products that could prove to be short-lived, which is why policymakers are keeping a close eye on another measure: the change in prices after the removal of food and fuel costs. That measure, known as the core index, offered news that was even better than what economists expected, sending stocks higher as investors bet that the news would allow the Fed to raise interest rates by less than it otherwise would have.

The core index rose 4.8 percent year-on-year, up from 5.3 percent in the year to May. Economists had predicted a 5 percent increase. And on a monthly basis, the core index rose at its slowest pace since August 2021.

“This is promising news,” said Laura Rosner-Warburton, senior economist and co-founder at MacroPolicy Perspectives. “The puzzle pieces are starting to come together. But it’s only one report and the Fed has been burned by inflation before.

Slower inflation is undoubtedly good news, as it can further stretch consumer wages and cause less pain at the gas pump and in the supermarket aisle. But Federal Reserve officials are still trying to assess whether the cooling is likely to be rapid and complete. They don’t want price increases to linger at slightly higher levels for too long, because if they do, consumers and businesses could adjust their behavior in a way that makes faster inflation a permanent feature of the economy.

Given that, they can be careful when interpreting the news. Officials have indicated in recent weeks that they are likely to raise interest rates at their July 25-26 meeting.

Ms Rosner-Warburton said she thought a July move was still likely, but that the new inflation data could lay the groundwork for “an extended pause” after that. She added that a cooldown in car prices and slower rent increases should keep inflation moderating going, and she predicted that the Fed would not raise rates again this year after the July change.

The slowdown in inflation in June was due to sharp price falls in some important products and services. Airfares fell 8.1 percent compared to the previous month, and used cars and trucks fell 0.5 percent. Prices for new vehicles remained flat compared to May.

Not all of these changes will necessarily be permanent: airfares, for example, are not expected to continue to fall as much as in this report. But for the Fed, there were other encouraging signs that the cooling is broad enough to be sustainable.

First of all, the cost of housing, as measured by the consumer price index, which depends on rents, is falling sharply. This is expected to continue in the coming months. An index that tracks primary housing rents slowed to a 0.46 percent change in June, the weakest increase since March 2022.

Car prices are also cooling. After years when shortages of semiconductors and other parts limited supply, making it difficult to meet the burgeoning demand, discount car dealer lots are making another comeback. Stocks are running up again and consumers have less appetite for new cars.

“It’s different from years past, and even different from the fall,” says Beth Weaver, who runs a Buick GMC car dealership in Erie, Pennsylvania. “Interest rates have certainly weighed on demand.”

And more broadly, price increases for a basket of services excluding energy, food and housing costs – a metric the Fed is watching closely – continued to slow in June.

But despite all the recent progress, inflation remains above the rate of increase that was normal before the 2020 pandemic. And the economy still maintains momentum, with strong job and wage growth, which could give companies the means to continue raising prices . That’s why Fed officials are hesitant to say they’ve won the battle against inflation.

“It would be a mistake” to “declare victory too soon,” Loretta Mester, the president of the Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland, said during a phone call with reporters this week.

The Fed officially aims for an average inflation rate of 2 percent over time, although it defines that goal using a separate inflation measure called the Personal Consumption Expenditures Index. That meter is also slowing down remarkably, and the June reading is scheduled for release on July 28.

Even if central bankers are likely to interpret the slowdown cautiously — knowing that price increases have previously slowed and then accelerated again — many commentators hailed the new data point as the latest sign that the economy may be slowing cautiously.

Officials at the Fed have been trying to secure a “soft landing” in which inflation slows gradually and without requiring a major jump in the unemployment rate. Rate hikes work in part by slowing the job market and cooling wage increases, so the Fed’s fight against inflation and the strength of the labor market are closely linked.

“The continued decline in inflation is encouraging news for the outlook for the U.S. job market,” Julia Pollak, chief economist at ZipRecruiter, wrote in response to the new release. “It increases the likelihood that the Fed can pause rate hikes after a final hike in July, and gradually lower rates through 2024.”