A large technology company with billions of users introduces a new social network. Leveraging the popularity and size of its existing products, the company aims to make the new social platform a success. In doing so, it also plans to crush a leading competitor’s app.

If this sounds like Instagram’s new Threads app and its push against its rival Twitter, think again. It was 2011 and Google had just rolled out a social network called Google+, which was intended to be the “Facebook Killer.” Google pushed the new site to the attention of many of its users who relied on its search and other products, expanding Google+ to over 90 million users within its first year.

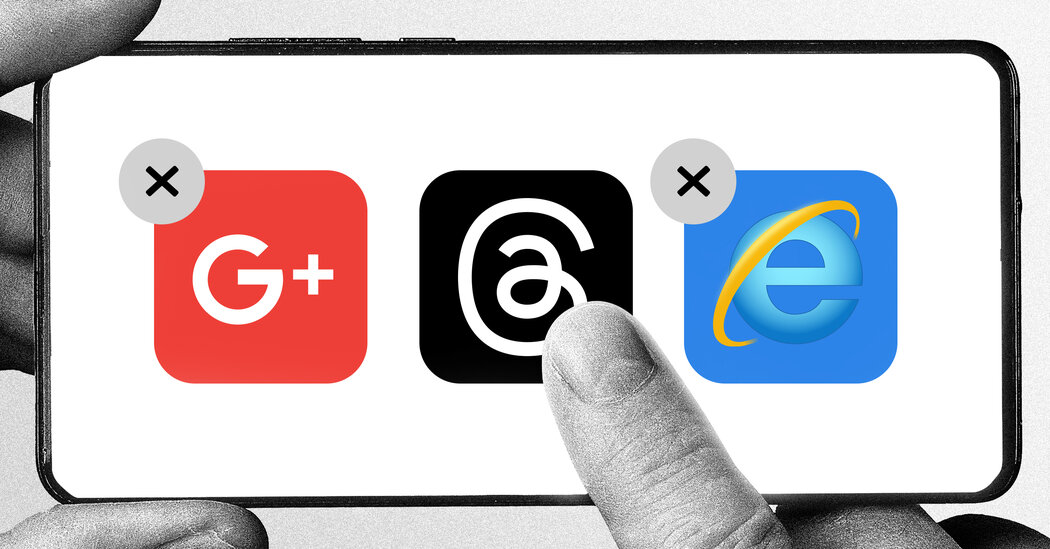

But in 2018, Google+ was relegated to the ashes of history. Despite the internet search giant’s massive audience, the social network failed to catch on as people continued to flock to Facebook — and later to Instagram and other social apps.

Throughout Silicon Valley’s history, large technology companies have often become even larger technology companies by using their scale as a built-in advantage. But as Google+ shows, greatness alone is no guarantee of winning the fickle and fashionable social media market.

This is the challenge Mark Zuckerberg, the CEO of Meta, which owns Instagram and Facebook, now faces as he tries to unseat Twitter and make Threads the premier app for real-time, public conversations. If engineering history is any guide, size and scale are solid footholds – but in the end, they can only go so far.

What comes next is much more difficult. Mr. Zuckerberg needs people to find friends and influencers on Threads in the casual and sometimes weird ways Twitter has managed to achieve. He has to make sure Threads isn’t full of spam and scammers. He needs people to be patient with app updates in the works.

In short, he needs users who find Threads attractive enough to keep coming back.

“If you launch a gimmick app or something that isn’t fully featured yet, that could be counterproductive and you could see a lot of people walking out the door again,” said Eric Seufert, an independent mobile analyst who closely monitors Meta’s . apps.

At the moment, Threads seems to be an overnight success. Within hours of launching the app last Wednesday, Mr. Zuckerberg said 10 million people had signed up for Threads. By Monday, that had risen to 100 million people. It was the first app to do so in that time frame, surpassing chatbot ChatGPT, which gained 100 million users within two months of its release, according to analytics firm Similarweb.

Mr. Seufert, the mobile analyst, called the numbers Threads collected “objectively impressive and unprecedented.”

Elon Musk, owner of Twitter, seems annoyed by Threads’ momentum. With 100 million people, Threads is rapidly rising to some of Twitter’s last public user numbers. Twitter announced it had 237.8 million daily users last July, four months before Musk bought the company and took it private.

Mr. Musk has taken action. On the same day last week that Threads was officially unveiled, Twitter threatened to sue Meta over the new app. On Sunday, Mr. Musk called Mr. Zuckerberg a “cuck” on Twitter. He then challenged Mr. Zuckerberg to a contest to measure a specific body part and compare whose body part was bigger, next to a ruler emoji. Mr. Zuckerberg has not responded.

(Before Threads was announced, Mr. Musk separately challenged Mr. Zuckerberg to a “cage match.”)

What Mr. Musk lacks on Twitter, Mr. Zuckerberg has in abundance at Meta: a huge audience. More than three billion users regularly visit Mr. Zuckerberg’s constellation of apps, including Facebook, Instagram, WhatsApp, and Messenger.

Mr. Zuckerberg has a lot of experience urging millions of people in those apps to use another app. For example, in 2014, he removed Facebook’s private messaging service from the social network’s app and forced people to download another app called Messenger to continue using the service.

Threads is now closely associated with Instagram. Users must have an Instagram account to sign up. People can import their entire followlist from Instagram to Threads with just a tap of the screen, eliminating the need to search for new people to follow on the service.

On Monday, Mr. Zuckerberg suggested he could do more to drive Threads’ growth. He hadn’t “turned on many promotions yet” for the app, he wrote in a Threads post.

Some users have wondered why Threads seems to have made its debut without some of the basic features used within Instagram, such as a search function that allows people to browse trending hashtags.

“There are a lot of features that Threads didn’t launch with, possibly by design, to keep it brand safe” and minimize controversy from the start, said Anil Dash, a tech industry veteran and writer. “What does that do to the long-term interest of the network?”

Adam Mosseri, the head of Instagram, said in a Threads post Monday that there was an ongoing list of new features to be added to the new app that people have been asking for. “They say ‘make it work, make it great, make it grow,'” he wrote, adding, “I promise we’ll make this thing great.”

But adding a new app to a company’s existing products can eventually run out.

In 2011, after Larry Page, Google’s co-founder and CEO at the time, cloned Facebook with Google+, users quickly grew bored with the novelty of the new social network and stopped using it. Some saw Google+ as something forced upon them while they were simply trying to access their Gmail.

Former Google employees describe the product as “fear based“Built only in response to Facebook and without a clear vision of why people should use it over a competing network. In a post-mortem of what went wrong, an ex-Googler wrote that Google+ defined itself primarily by “what it wasn’t – namely Facebook.”

Sure, Mr. Zuckerberg can pull a Bill Gates with Threads. Mr. Gates, a founder of Microsoft, built his empire on Windows, the operating system that powered a generation of personal computers, and then successfully used that scale to crush competitors.

Once Windows dominated PCs, Mr. Gates famously released other products for free with the software. When he did so in 1995 by packaging the Internet Explorer web browser with Windows, Internet Explorer quickly turned into the default browser on millions of computers, overtaking the then-dominant Netscape browser in just four years.

Still, Mr. Gates was eventually stung by the tactic. In 1998, the Justice Department sued Microsoft for unfairly using Windows’ market power to eliminate competition. In 2000, a federal judge ruled against Mr. Gates’ company, saying that Microsoft had put an “oppressive thumb on the scale of competitiveness.”

Microsoft later settled with the government and agreed to make concessions.