As the Cold War was winding down, physicist Lewis Branscomb feared that America’s economic and scientific superiority was in danger. Declining scientific literacy and critical thinking in American education, he believed, could have disastrous consequences for the country.

Students, he told The MacNeil/Lehrer NewsHour on PBS in 1986, “don’t need to know a lot of facts about science, but they really need to understand how to think the way scientists think—that is, in a problem-solving approach.” , given a complex environment to make decisions.”

Whether in academia, the private sector or government, Dr. Branscomb has made it his mission to advance science and give it a greater role in public policy. He held out hope for a better future through technology, but only if scientists and policymakers could get the public behind the idea.

Dr. Branscomb, who has worked his entire career at the intersection of science, technology, policy and business, died May 31 at a health care facility in Redwood City, Calif., his son, Harvie, said. He turned 96.

Dr. From 1969 to 1972, Branscomb headed the National Bureau of Standards (now the National Institute of Standards and Technology), the federal government’s authoritative standards and measurement laboratory. He later served as IBM’s chief scientist and was a professor at Harvard University, authoring hundreds of papers and authoring or contributing to about a dozen books.

Dr. Branscomb began working for the government in the aftermath of World War II, and nearly six decades later advised the Senate on America’s vulnerabilities following the September 11, 2001 terrorist attacks.

In the meantime, he developed basic scientific techniques and refined measurements at the National Bureau of Standards; helped IBM transform its computers from hulking mainframes, which could cost more than a car, into something that would fit in a home office; and advised multiple presidents, including Lyndon B. Johnson, Richard M. Nixon, and Ronald Reagan, on policy matters, particularly the space program.

Irving Wladawsky-Berger, a former IBM researcher and executive, said in a telephone interview that Dr. Branscomb played an important role with the company as it led the development of technology such as computer memory and storage, networking products and semiconductors. Dr. Branscomb “had the vision to make IBM a world-class research company,” he said.

Dr. Branscomb called for technological growth to be driven by private industry as well as the Department of Defense and other government agencies, expressing concern that the end of the space race with the Soviet Union had led to a diminished NASA.

“Whereas NASA once challenged the industry to go beyond what had ever been done before,” he said in congressional testimony in 1991, “today the best commercial companies are taking more risks, expanding their technology, reaching performance and reliability levels that NASA no longer achieves or even expects.”

It fell to the scientists to rekindle society’s enthusiasm for their work, wrote Dr. Branscomb in “Confessions of a Technophile” (1995), arguing that it was for the scientific community “to recognize the legitimacy of the public’s desire to participate, however superficially, in the excitement of a new discovery.”

Lewis McAdory Branscomb was born on August 17, 1926 in Asheville, NC, to Harvie and Margaret (Vaughan) Branscomb. His father was dean of the school of theology and library director of Duke University and then chancellor of Vanderbilt University in Nashville. His mother oversaw the planting of magnolia trees on the Vanderbilt campus and was memorialized there with a statue.

A promising student from an early age, Lewis dropped out of high school and received accelerated training at Duke as part of a naval program to train future scientists.

He earned a bachelor’s degree in physics at age 19 and then served as an officer in the Naval Reserve. He left the Navy in 1946 to enroll at Harvard, where he received his master’s degree a year later and his doctorate in 1949.

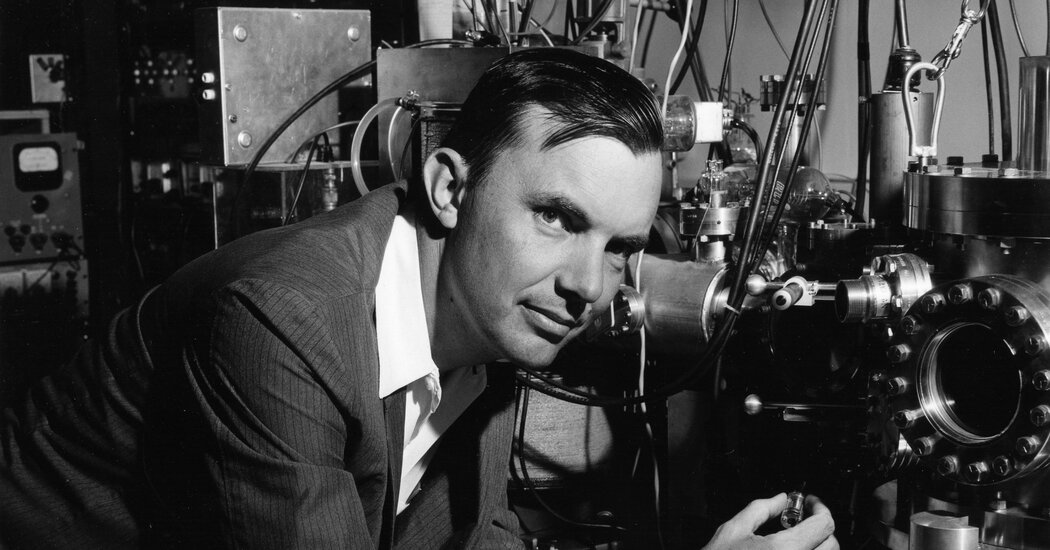

In 1951 dr. Branscomb a research physicist who studied the structure and spectra of molecular and atomic negative ions for the National Bureau of Standards, a division of the Department of Commerce and one of the oldest federal natural sciences research laboratories.

In the early 1960s, he moved from Washington to Boulder, Col., where he helped found the Joint Institute for Laboratory Astrophysics, now known as JILA, a collaboration between the Bureau of Standards and the University of Colorado that sought to advance astrophysical research. Later he was president of the institute.

In the mid-1960s, he joined President Johnson’s scientific advisory committee as the Apollo program prepared to land astronauts on the moon in 1969. That year, President Nixon appointed him director of the Bureau of Standards, a position he he held until he left for England. IBM in 1972.

He was IBM’s chief scientist until 1986, when the company made components for the space shuttle, built computer mainframes, and entered the personal computer market against competitors like Apple and Tandy.

In 1980 dr. Branscomb is the chairman of the National Science Board, which sets National Science Foundation policy and advises Congress and the President. He held that position until 1984.

Dr. Branscomb left IBM to become a professor and director of the Science, Technology and Public Policy Program at Harvard’s John F. Kennedy School of Government. He also served on the boards of directors of companies such as Mobil and General Foods.

Books he wrote and edited include “Empowering Technology: Implementing a US Policy” (1993) and “Making the Nation Safer: The Role of Science and Technology in Countering Terrorism” (2002, with Richard Klausner and others).

Dr. Branscomb married Margaret Anne Wells, a lawyer and computer communications expert, in the early 1950s. She died in 1997.

In 2005, he married Constance Hammond Mullin, with whom he lived for many years in the La Jolla neighborhood of San Diego. She survives him.

In addition to his wife and son, his survivors include a daughter, KC Kelley; three stepchildren, Stephen J. Mullin, Keith Mullin, and Laura Thompson; and a granddaughter.

In the foreword to “Confessions of a Technophile,” Dr. Branscomb described himself as an “incurable optimist” who was “driven all my life by the deep conviction that good prospects for humanity depend on the judicious and creative use of technology.”

He added in a footnote that he was an optimist not by logic but “by assertion.”