Public domain

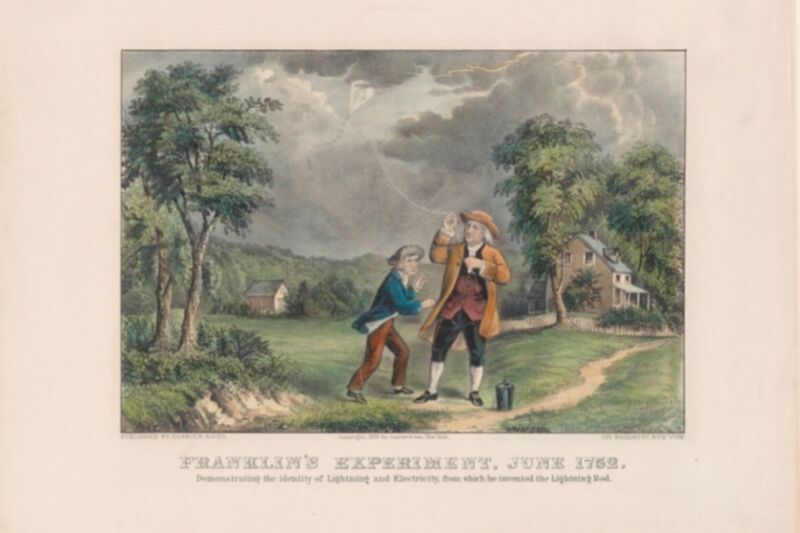

Most Americans are familiar with the story of Benjamin Franklin and his famous 18th-century experiment in which he attached a metal key to a kite during a thunderstorm to see if lightning would pass through the metal. This is largely due to the many iconic illustrations commemorating the event that found their way into the popular imagination and became part of our shared cultural lore. But most of those classic illustrations are riddled with historical errors, according to a new paper published in the journal Science and Education.

Franklin’s research into electricity began as he approached 40 after his flourishing career as an entrepreneur in the printing business. His scientific interest was sparked in 1743 when he saw a demonstration by scientist/showman Archibald Spencer, known for performing various amusing parlor tricks with electricity. He soon began a correspondence with a British botanist named Peter Collinson and began recreating some of Spencer’s impressive parlor tricks in his own home.

He had guests rub a tube to create static electricity and then had them kiss, which caused an electric shock. He designed a fake spider that hung from two electrified wires so that it seemed to swing back and forth on its own. And he invented a game called “Treason,” where he wired a portrait of King George so that anyone who touched the monarch’s crown would be shocked. And he once infamously shocked himself when he tried to kill a turkey with electricity.

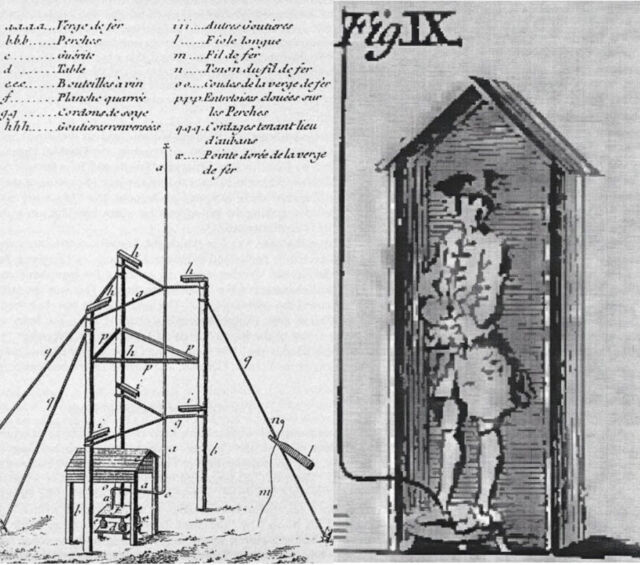

Among his many insights into the phenomenon, Franklin noted how sparks jumped between objects and concluded that lightning was just a huge electrical spark, similar to that produced from charged Leyden jars. To test his theory of the nature of lightning, Franklin published a paper proposing an experiment using a raised iron rod wire to “draw down the electrical fire” from a cloud, with the researcher standing on insulated ground in the protection of a fence similar to a soldier’s guard post. Franklin reasoned that an electrified cloud passing over the spiked rod would draw electricity from the cloud so that if the man moved the knuckle of his finger closer to the metal rod, there would be sparks.

There is no record of Franklin conducting his sentinel experiment, according to Breno Arsioli Moura, a science history and lecturer at Brazil’s Federal University of the ABC, who wrote the new paper. But a Frenchman named Thomas-Francois D’Alibard did. D’Alibard read Franklin’s published paper and used a 50-foot (15 m) vertical rod to perform his version of the Paris Guardhouse Experiment on May 10, 1752. Others across Europe soon followed suit. It was a rather dangerous experiment, as evidenced by the unfortunate Georg Wilhelm Reichmann. He also tried to reproduce the experiment, but a glowing charge ball traveled down the string, jumped to his forehead and killed him instantly—perhaps the first documented case of ball lightning.

Public domain

It seems that Franklin was unaware of these attempts when he devised his simpler kite experiment along similar conceptual lines. The established account goes something like this: Anticipating a thunderstorm in June 1752, on the outskirts of Philadelphia, Franklin built a kite from two strips of cedar wood nailed together in the shape of a cross, or “X,” with a large silk handkerchief which formed the body, because silk withstood the rain and the wind of a thunderstorm. He attached a wire to the top of the kite to act as a makeshift lightning rod. Hemp cord was attached to the underside of the kite to provide conductivity and attached to a Leyden jar with a thin metal wire. Also tied to the hemp was a silk rope held by Franklin. The ropes of hemp and silk were connected with a metal key.

Next, Franklin went under a shed to make sure he held a dry section of the silk cord to keep it from becoming conductive. Franklin’s son, then 21, helped him lift the kite, and they sat down and waited. Possibly, Franklin observed the loose filaments of rope “standing up,” indicating electrification. He pressed his knuckle on the key and was rewarded with an electric spark. This proved that lightning was static electricity. Contrary to popular myth, Franklin was not struck by lightning; if he had been, he probably wouldn’t have survived. The spark was due to the kite/key system being in a strong electric field.

According to Moura, there are two primary historical sources for the aforementioned details about the kite experiment. One is a short letter written by Franklin to Collinson in October of that same year and is included in The Philadelphia Gazette (with some textual differences). The other account was written 15 years later by Franklin’s friend and colleague, Joseph Priestley, in his 1767 treatise, The history and current state of electricity