A cluster of regional banks tried to convince the public of their financial soundness on Thursday, even as their share prices plummeted and investors placed bets on what the next drop might be.

The uproar raised questions about the lenders’ future, signaling a new phase in the crisis that began two months ago with the collapse of Silicon Valley Bank and Signature Bank, and was punctuated Monday by the repossession and sale of First Republic Bank.

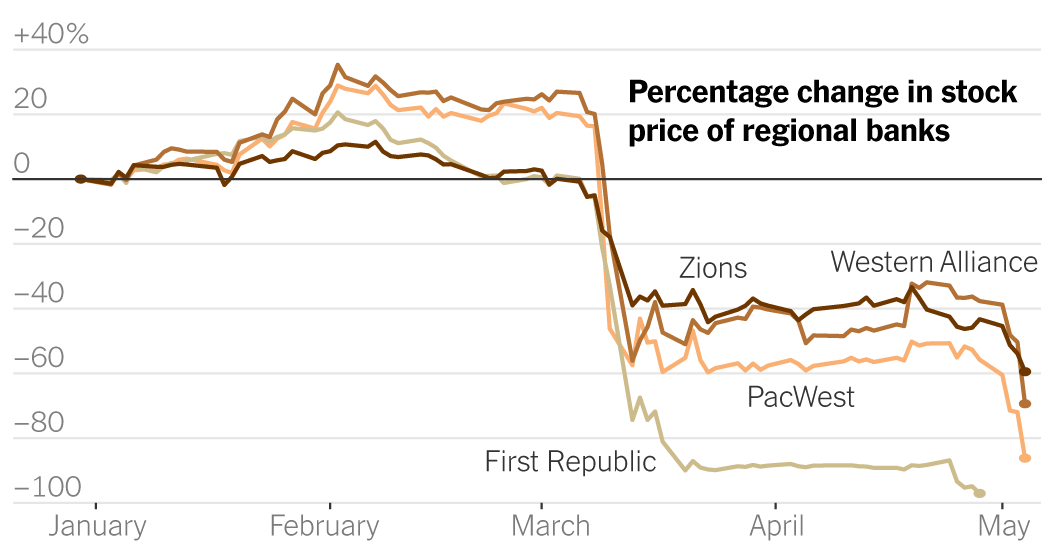

PacWest and Western Alliance were in the eye of the storm, despite the companies’ protestations that their finances were sound. Shares of PacWest lost 50 percent of their value Thursday and Western Alliance’s shares fell 38 percent. Other medium-sized banks, including Zions and Comerica, also reported double-digit percentage declines.

Unlike the banks that failed after depositors rushed to collect their money, the lenders now under pressure have reported relatively stable deposit bases and are not sitting on mountains of soured loans. They are also much smaller than Silicon Valley Bank and First Republic, which each had about $200 billion in assets when they collapsed. PacWest, based in Los Angeles, has about $40 billion in assets and Western Alliance, headquartered in Phoenix, has $65 billion in assets. Both banks have fewer than 100 branches.

The most immediate threat facing the banks is a crisis of confidence, analysts say. Headlines about their rising share prices could scare savers and shake up the banks’ ability to operate normally.

“How do we get out of here?” said Christopher McGratty, chief of U.S. banking research at Keefe, Bruyette & Woods. “I think we’re still looking for that answer.”

Shares of PacWest and Western Alliance were halted dozens of times on Thursday as their massive price swings broke the stock market’s guardrails that were put in place to prevent a sell-off from spiraling out of control. The turmoil also raised the specter of concerted action by short sellers, the traders who bet on falling stock prices and are sometimes blamed for fueling market volatility.

The Biden administration was closely monitoring markets, “including short-selling pressure on sound banks,” White House Press Secretary Karine Jean-Pierre told reporters Thursday. Gary Gensler, the chairman of the Securities and Exchange Commission, said in a statement on market conditions that the agency was “focused on identifying and prosecuting any misconduct that could threaten investors, capital formation or the markets more broadly.”

Justin D’Ercole, a founder of ISO-mts Capital Management, a bank-focused fund, said trading on Thursday felt “exceptionally panicky” and “overblown”.

“There was extreme concern about these banks without much reasoning,” he said.

Trading reminded that the crisis may still be ongoing, contradicting predictions that the situation would calm down after JPMorgan Chase reached an agreement with government officials to take over the ailing First Republic.

Regulators agreed to lurk billions of dollars in potential losses on First Republic’s books, and JPMorgan CEO Jamie Dimon declared immediately after the acquisition that “this part of the crisis is over.”

On Wednesday, Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome H. Powell said at a news conference that conditions had calmed since the collapse of Silicon Valley Bank. Hours later, PacWest’s stock began its latest nosedive.

It has now become clear that investors are not convinced that the remaining regional lenders can remain viable. And while there is no reason for any company to be immediately toppled by falling share prices, the outlook remains uncertain, with investors still bruised by the initial turbulence in March.

“Institutional investors have lost confidence in banks,” said Julian Wellesley, banking analyst at Loomis Sayles. “I hear from a lot of people that the stock prices aren’t right, but still no one wants to come in and buy.”

This is worrying for the banks themselves, indicating that their claims to sound financial health are not yet having the desired effect.

There’s a limit to how long a publicly traded company can limp with a falling stock price before they frighten depositors and anger shareholders.

Even before this week’s commotion, savers were increasingly concerned about the safety of their money following the collapse of Silicon Valley Bank. According to a Gallup poll conducted in late April, 48 percent of American adults said they were concerned about the money they had in deposits with financial institutions.

The Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, which guarantees bank accounts up to $250,000, released a report this week saying it would consider changes to its rules. The agency suggested it could try to offer business checking accounts higher levels of insurance, which would make companies feel comfortable continuing to pay employees without creating the “moral hazard” that could arise if all deposits were broadly guaranteed. would be.

Legislation from Congress is needed to change the current Deposit Guarantee Scheme.

Amid the relentless stock declines, some blamed another bogeyman: investors betting on a fall in a stock’s price. According to estimates from S3 Partners, a data provider, short sellers have wagered nearly $7 billion against regional banks this year, and could send those profits to new targets.

PacWest appeared most squarely in their sights, at least for now. Nearly 20 percent of the bank’s shares are currently on loan to short sellers, who sell them and hope to buy them back later when shares fall, according to data from S3. Nearly 8 percent of Western Alliance shares are similarly lent.

Before First Republic was seized, more than 36 percent of its stock had been lent.

On Thursday, Western Alliance blamed those short sellers for the turmoil, suggesting they were behind “false stories about a financially sound and profitable bank” while issuing a statement denying a report that it was considering a sale.

Such attacks rarely work against short sellers, and the banks’ revelations on Wednesday and Thursday, which said their depositors were not fleeing and their capital base was sound, didn’t seem to either.

One possible solution to put an end to such attacks would be to ban short selling, which is what regulators did in 2008 when the financial crisis erupted. It’s not clear whether such bans worked as intended and when asked Thursday, a spokesman for the Securities and Exchange Commission said the agency is not considering limits on short selling of regional bank stocks.

“I’m not sure yet if Washington is going to do anything,” said Ian Katz, policy analyst at advisory Capital Alpha Partners. He underscored the concern: “What’s going to stop this right now?”

In a vote of confidence, executives at Zions, a Utah-based lender with about $90 billion in assets, spent nearly $2 million investing in the bank’s declining shares in recent days, according to regulatory filings.

The lenders now under pressure also seem eager to open their books to reassure investors. First Republic mostly remained silent as the company collapsed.

PacWest released a statement Thursday night saying it had been “approached by several potential partners and investors”. Hours earlier, a report that it was exploring its options caused a 50 percent slump in the share price in after-hours trading on Wednesday.

The bank said it had not seen an “extraordinary” deposit outflow since the collapse of First Republic, saying deposits were $28 billion on Tuesday, slightly down from the end of April.

Western Alliance also released updated financial details on Wednesday, noting it has “experienced no unusual deposit flows” in recent days. It said deposits had increased by $1.2 billion since the end of March.

Western Alliance shares were still shaky, especially after The Financial Times reported that the bank had hired advisers to guide it through a potential sale – an indication that the lender needed help. Shares recovered from their worst losses after Western Alliance denied the report, but still ended the day significantly lower.

“The stock is not the company and the company is not the stock,” said Timothy Coffey, banking analyst at Janney Montgomery Scott. “But the loss of confidence in a financial institution can be difficult to repair.”

Reporting contributed by Jeanna Smilek, Alan Reportport, Maureen Farrell, Stacy Cooley And Lauren Hirsch.