Edward H. Meyer, an empire-building CEO who, using a rock-solid management style and a laser focus on even the smallest details, transformed a mid-sized New York ad agency into the global powerhouse known as Gray Group, died Tuesday at his Manhattan apartment . He turned 96.

His death was confirmed by a spokeswoman for Grey.

Mr. Meyer joined Gray Advertising, as it was then known, in 1956 as an account services manager, when the agency was billing about $34 million a year.

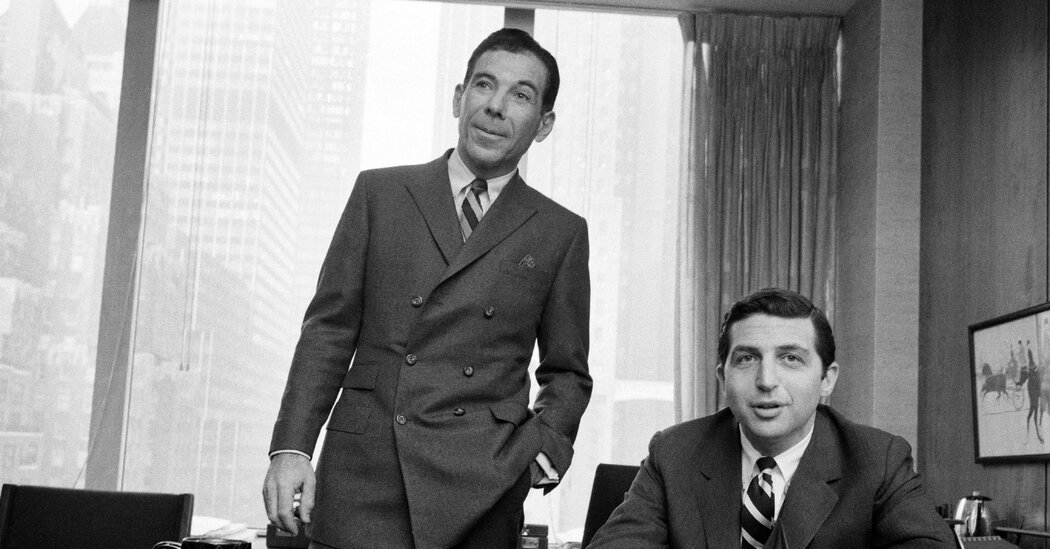

He was named president in 1968 and took the reins as chairman and CEO in 1970. Over the next 35 years, he built Grey, one of the last major agencies to remain independent, into a behemoth costing $4.2 billion, according to a company spokeswoman. when it was sold to British advertising and communications giant WPP in 2005 for $1.5 billion.

As a manager, Mr. Meyer was anything but passive. He demanded performance at all levels and had an uncompromising drive that drew comparisons to corporate barons like Rupert Murdoch and Sumner Redstone.

“Ed inspires awe among staffers of every rank,” noted a 2003 profile in Adweek. “He also instills fear.” The article quoted a former grizzled middle manager as saying that employees would often go silent as soon as Mr. Meyer entered an elevator, and that some outside his office would visibly shake before meetings.

Although Mr. Meyer was graceful and often astutely witty in interviews, he did not evade such characterizations. “I just tend to think I’m not benevolent,” he told Adweek. “But everyone says, ‘Boy, he admires brains, he likes people who get it done. If you can meet those criteria, you’ve made it at Grey.'”

Mr. Meyer believed that serving customers required much more than taking their top executives to four-star restaurants.

“I built my career and the agency on the belief that customers come first, and it’s the job of the guy running the agency to know their needs,” said Mr. Meyer in 2006 to New York Times advertising columnist Stuart Elliott. Not what they like for dinner, but their advertising needs, better than anyone else at the agency.

Mr. Meyer lived up to his words. For example, in 1988, he took turns cleaning shrimp and waiting tables at a Red Lobster restaurant in Orlando, Fla. seafood lover in you”

As a waiter he had his shortcomings and spilled coffee on one customer. “She told me there was no need to apologize,” he later recalled, “because it was nice to see someone my age doing that job.”

Over the years, customers have taken note. “Ed is Gray and Gray is Ed,” a Procter & Gamble executive, a regular for decades, told Adweek.

Such hands-on dedication made even more sense for Mr. Meyer, given that he had an unusual amount of skin in the game.

“I was one of the few guys who owned a big part of the agency he ran,” he told Mr. Elliott after Gray’s sale, which is estimated to have netted him nearly $500 million. “Every penny I had was in this, so I had more at stake than anyone else”

“I was sweating it harder,” he added. “I was drowning out people because I couldn’t afford to be a nice guy.”

Edward Henry Meyer was born in New York City on January 8, 1927, the second of three children of Irving Meyer, a manufacturer of children’s clothing, and Mildred (Driesen) Meyer.

After graduating from the private Horace Mann School in the Bronx, he enrolled at Cornell University. He took time off in 1945 to serve two years on the United States Coast Guard Reserve and, upon returning to Cornell, earned a bachelor’s degree in economics in 1949. now Macy’s Inc.).

Mr. Meyer began his half century in advertising in 1951 when he took a job at the Biow Company, a small agency. There he began his long and fruitful relationship with Procter & Gamble, the Cincinnati-based packaged goods giant, by working on his Lava soap opera account.

His work with Procter & Gamble continued five years later when he jumped to Gray. It didn’t take long for him to get results.

In 1959, the agency won the account for Procter & Gamble’s Ivory Flakes laundry soap, a brand that had long been in a slump as competitors touted its new and improved ingredients.

As an account manager, Mr. Meyer research on the brand’s most loyal consumers, who turned out to be new mothers. In response, Gray focused on the brand’s perceived purity, arguing that Ivory Flakes were soft and gentle enough to wash baby clothes and cloth diapers.

A resulting television spot showed a bow-tie professor who calls himself “the world’s only baby language translator” deciphering a little girl’s fussy chatter as a result of wearing scratchy diapers washed in competitors’ soap. After just a few months, the brand had reversed an 11-year decline in sales, according to a former Gray executive who was interviewed for an internal agency history compiled in 1992.

Mr. Meyer, an early proponent of globalization for the industry, considered global reach to be key to his agency’s growth. He also expanded into related fields such as public relations, media buying and direct marketing.

“When I took over, it was a domestic advertising agency in the United States just starting to explore the world,” said Mr. Meyer on Gray in a 2001 interview with Business Today magazine. Under his leadership, he continued, “Grey became a truly global agency, in the ’60s and ’70s, which was the right time to do it, because you can’t do it anymore.”

Mr. Meyer is survived by his wife, Sandy; his son Tony; his daughter Meg; and five grandchildren.

He retired in 2006, one year after selling the agency. In 2014, he and his wife donated $75 million to Weill Cornell Medicine in Manhattan to expand and consolidate the cancer care and research programs under the Sandra and Edward Meyer Cancer Center.

To many in the industry who had come to see Mr. Meyer and Gray as one and the same, his departure after so many decades seemed almost unimaginable. Mr. Meyer apparently agreed. In an interview with Chief Executive magazine at the end of his career, Mr. Meyer’s seemingly endless tenure as Gray’s chief.

“When do I retire?” he said. “To paraphrase Warren Buffett, five years after my death.”