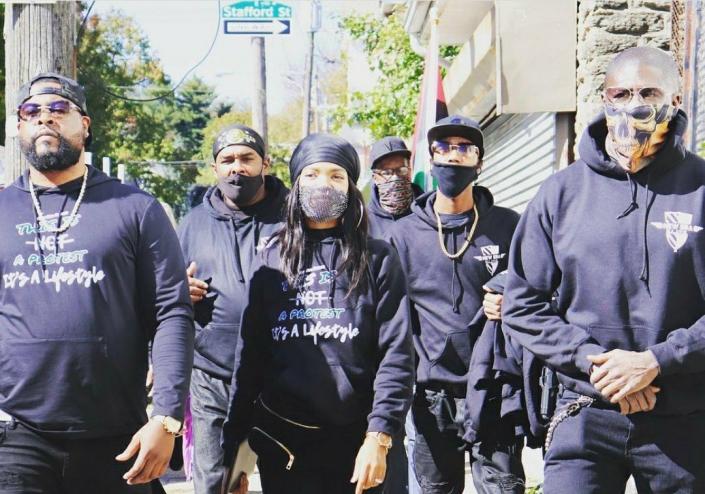

On the eve of Black History Month this year, a Detroit community group went viral after sharing clips on social media of its members, many dressed in all black and armed with long guns, helping women in the city by pumping gas into their vehicles and load groceries into their car.

The group’s open display of guns — broadly legal in Michigan — was greeted by many people, not for being threatening, but for protecting black women in dangerous neighborhoods at night.

The group, New Era Detroit, has been conducting this kind of public safety work on the city’s most crime-ridden streets for nearly a decade.

“We’re doing this out of love,” Nilajah Alonzo, one of the New Era Detroit leaders, told Yahoo News.

The group’s Instagram page features videos of members escorting childcare workers home late at night from a daycare center just a block away from where a murder had recently taken place. Another social media post shows members conducting a workshop with children on conflict resolution.

“We’re not trying to be crime heroes or anything like that,” Alonzo said. “We’re just trying to educate and uplift our community.”

Launched in August 2014, New Era Detroit was founded by Zeek Williams as a call to action for black men in the city to step up and be more present to fight rampant crime and violence in poverty-stricken areas around the city. The call went out as robberies of women in and around supermarkets and gas stations became more common.

The group calls itself a ‘mudroots’ organization because of its approach.

“We say ‘mudroot,’ because we get under the grass, we get into the mud, we get into the community, we get into the streets, we get into the ‘hoods, to connect with people and interact with them. to go,” Alonzo said. “So they know there are people who care.”

Over the past decade, Detroit has consistently ranked as one of the most dangerous major cities in the U.S. in 2022, while preliminary police data showed an 11% reduction in violent crime from the previous year, carjackings increased by 21%, and other property crimes, including burglaries saw a significant spike. In addressing these issues, according to Williams, New Era Detroit’s purpose is based on the idea that black people with structure can protect and serve their own neighborhoods and streets.

“We want to be in a position where, when things happen or something happens in our community, the police don’t have to be there all the time,” Williams told MSNBC earlier this month, adding that the organization’s members have guns. not to incite violence, but to protect innocent people. “We believe able-bodied men can take the stage and do more to guard their community.”

The group has managed to maintain a working relationship with the city’s police department.

“We have a great relationship with New Era Detroit,” says Sgt. Jordan Hall told Yahoo News. “We even have an appointment where they call us [ahead of events]so nothing should be alarming to officers if they see someone with a gun.

Detroit’s challenges are complex and rooted in the Rust Belt’s history. Once the global center of the auto industry, Detroit was the fourth largest city in the US in the 1920s. The population grew explosively to almost 2 million inhabitants at its peak in 1950. But automation slowed down the boom in blue-collar work. Racial tensions rose and deadly riots rocked the city in 1967 as tens of thousands of white residents left for the suburbs. Detroit struggled financially and in 2013 became the largest U.S. city to file for bankruptcy. Today it has the highest rate of concentrated poverty of the 25 largest metropolitan areas in the United States.

Over the past seven decades, the steady decline in the city’s population, of which 77% are black people, has left the city with only a third of its peak total.

In a show of progress, the city has been working towards a turnaround, with the emergence of new restaurants and bars, a growing arts scene and a revitalized downtown. But a Michigan State University study revealed that much of the progress has been confined to a 7-square-mile radius, in a 139-square-mile city.

That leaves much of the city where residents feel abandoned.

“We are looking at a system that is really not broken. It just hasn’t had us in mind — or protected us,” Williams told NBC. “Why don’t we do more to guard our own communities?”

Many people compare Williams’ New Era Detroit to the original Black Panther Party, which emerged from the civil rights movement of the 1960s. Founded by Huey P. Newton and Bobby Seale in Oakland, California, in 1966, the idea was for black residents to act as vigilantes in their own communities. As they evolved, the Panthers began to arm themselves, in a show of violence, often wearing a uniform of blue shirts, black trousers, black leather jackets and black berets. Unlike the Detroit organization, which is primarily concerned with tackling issues such as community crime, the Black Panthers sought to protect black residents from instances of police brutality.

“The Panthers were really focused on possible police brutality against people in the community,” journalist Mark Whitaker, author of “Saying It Loud: 1966 – The Year Black Power Challenged the Civil Rights Movement,” told Yahoo News. “New Era is equally concerned about the danger that ordinary, law-abiding citizens in the inner city face from other black people who could harm them. … So for young people to help protect other people in the community, I think it’s great to see.

Other cities with similar challenges have noticed this. The original Detroit group, under the New Era Nation umbrella, has formed more than a dozen chapters in cities such as Dallas, Atlanta, Cleveland, and Baltimore. The self-sufficiency movement has also generated interest abroad, in Jamaica, the UK and Nigeria, according to Alonzo.

“We are all leaders and everyone gets the chance to lead,” he said. “We have chapters in every city, so it’s not going to die with one person. We set up a structure where someone is in charge, no matter what. We appreciate being compared to other groups, but if we insist that we are all leaders, it cannot die.”

Whitaker warns against scaling up too quickly.

“The lesson of the Black Power period is to stay local,” he said. “That’s where you can do the most good, and that’s where people need you the most, and people aren’t adequately helped by police or local government.”

_____

Cover thumbnail: Stephen Maturen/Getty Images