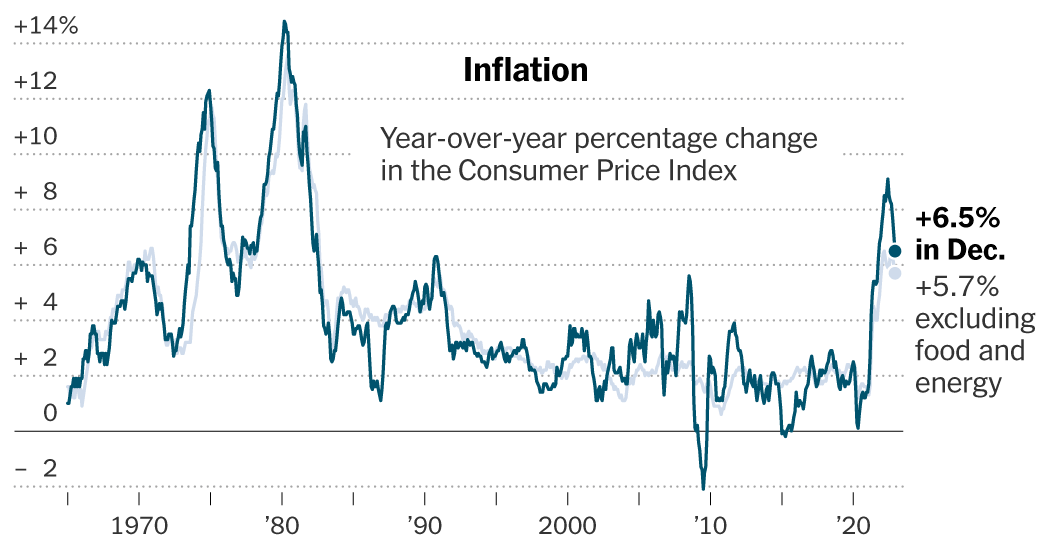

Inflation slowed year-over-year for a sixth straight month in December, a relief for households and an encouraging signal to the Federal Reserve and White House that could be the worst pandemic-driven inflationary outburst in history.

The consumer price index rose 6.5 percent year-to-date, up from 7.1 percent in November, as prices fell on a monthly basis for the first time in more than two years. Annual inflation was the lowest since October 2021, a pullback driven by falling gas prices and cheaper airline tickets.

Economists and Fed officials are more keenly focused on a so-called core inflation measure, which removes food and fuel prices to get a sense of underlying price trends. That measure ticked up on a monthly basis, but the annual measure slowed to 5.7 percent in December from 6 percent earlier.

Overall, the data provided the latest evidence that inflation is moderating significantly, bringing relief to consumers when they try to buy a used vehicle, take a road trip or buy new furniture. But price increases are still unusually fast for a number of goods and services, from food to car maintenance, and the key question now is how quickly and completely inflation will return to prepandemic levels of around 2 percent after a year and a half of rapid increases.

President Biden greeted the report enthusiastically, highlighting the role his policies — including efforts to cut gas costs — have played in helping prices rise more slowly. In remarks from the White House on Thursday, Mr. Biden said moderating inflation “is a real breakthrough for consumers, real breathing space for families and more evidence that my economic plan is working.”

For the Fed, the report confirms that the slowdown in price hikes officials have long expected is finally becoming a reality. That could help policymakers who have begun slowing the pace of rate hikes feel comfortable with even more incremental moves.

Inflation FAQs

What is Inflation? Inflation is a loss of purchasing power over time, meaning your dollar won’t go as far tomorrow as it did today. It is usually expressed as the annual change in prices for everyday goods and services such as food, furniture, clothing, transport and toys.

Fed officials last year adjusted their policies at the fastest pace in decades to try to curb rapid inflation, but with interest rates at higher levels and inflation showing early signs of slowing, they switched to an adjustment in December half point after a series of three-quarter rate moves. Now policymakers have made it clear that they are considering an even more modest quarter-point change in February.

The new inflation data likely supports the case for that softer path, which will give officials more time to see how their policies play out in the economy and how much more is needed.

“I expect we’ll see a few more rate hikes this year, but I think the days of raising them 75 basis points at a time are definitely over,” said Patrick Harker, president of the Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia. said in a speech on Thursday. “In my view, increases of 25 basis points going forward will be appropriate.”

Still, the new report did little to suggest that the problem of rapid price increases has been fully resolved, which is why central bankers are still expected to push borrowing costs at least slightly higher and leave them high for some time to keep price increases under control. gain control.

“This report really supports a downshift,” said Blerina Uruci, chief economist for the U.S. fixed income division at T. Rowe Price. “But I don’t think this changes the overall inflation picture: we are making progress in curbing inflation, but from a very high level.”

Several trends should help curb price increases this year. More muted cost changes for goods are expected to help cool overall inflation as supply chains recover. For example, used cars and trucks, a major driver of inflation in 2021 and early 2022, became cheaper last month. New cars also fell slightly in price.

Housing costs should also moderate later this year. Rising rents supported inflation in December and could push inflation higher for a while, but that is expected to reverse over time. Rents for newly rented apartments are starting to rise much more slowly, private data suggests, which will gradually feed into the government’s official inflation measure.

But there are still lingering risks. In particular, economic officials are watching closely what happens to prices for other services, including things like hotel rooms, tickets to sporting events and health care. They worry that services inflation – which is unusually fast – could cause prices to rise faster than the central bank’s target. The Fed aims for an average inflation rate of 2 percent, using a price measure different from but related to the consumer price index.

Prices for core services excluding housing costs, a metric closely monitored by both the Fed and economists, rose 0.3 percent month on month in December. That was an increase from 0.1 percent in November, according to calculations by Omair Sharif, founder of Inflation Insights.

Understand inflation and how it affects you

“What we’ve done is pivoted commodity inflation,” said Mr. Harker in a question-and-answer session after his speech. “Service inflation ex shelter is still very high.”

Many central bankers believe that to control services inflation, they must slow down the labor market and curb wage growth. Otherwise, companies facing higher labor bills will likely continue to pass these costs on to consumers.

“By far the biggest expense in that industry is labor,” Fed Chairman Jerome H. Powell said at his last press conference in December. “And we see a very, very strong labor market, one where we haven’t seen much weakening, where job growth is very high, where wages are very high.”

That is why central bankers have remained resolute, albeit more measured, when it comes to raising interest rates. Higher borrowing costs can discourage consumers from making major purchases, such as cars and homes, while slowing business expansion and ultimately curbing hiring and wage increases.

Investors do expect the Fed to raise rates a little more, but not as much as officials predict. Markets are betting that policymakers will announce a quarter-point step at their Feb. 1 meeting, pushing the key policy rate to 4.5 to 4.75 percent, but investors expect rates to fall below the peak of 5.1 percent. will continue that Fed officials have predicted.

“There is deep skepticism now,” said Ian Shepherdson, chief economist at Pantheon Economics, who thinks the central bank has done enough at this point to bring inflation back to normal. “I’m not sure there are many people in markets who believe they’re going for a walk, after walk, after walk.”

A big question is whether inflation will be able to slow down without sending the economy into a painful downturn. With price increases moderating, many on Wall Street and some in the central bank have expressed hope that a soft landing, in which inflation moderates without severe economic pain, is possible.

“I remain what I call a realistic optimist,” Susan Collins, president of the Federal Reserve Bank of Boston, said in an interview Wednesday. “There is a resilience that I continue to see in the economy, and that makes me optimistic that there is a way to reduce inflation without a significant downturn.”