There’s rarely time to write about every cool science story that comes our way. So this year we have another special Twelve Days of Christmas series of posts, highlighting a science story that has fallen through the cracks in 2022, every day from December 25 through January 5. Today: Why dinosaur mummies may not be as rare as scientists thought.

Under certain circumstances, dinosaur fossils may contain exceptionally well-preserved skin, something long thought to be rare. But the authors of a paper published in October in the journal PLoS ONE suggested that these dinosaur “mummies” may be more common than previously believed, based on their analysis of a mummified duck-billed khadrosaur with well-preserved skin that showed unusual telltale signs of scavenging. in the form of bite wounds.

In this case, the term “mummy” refers to fossils with well-preserved skin and sometimes other soft tissue. As we previously reported, most fossils are bones, shells, teeth, and other forms of “hard” tissue, but rare fossils are occasionally discovered that preserve soft tissues such as skin, muscles, organs, or even an eyeball. This can tell scientists a lot about aspects of the biology, ecology and evolution of such ancient organisms that skeletons alone cannot convey.

Last year, for example, researchers created a highly detailed 3D model of a 365-million-year-old ammonite fossil from the Jurassic period by combining advanced imaging techniques, revealing internal muscles never seen before. Another team of British researchers conducted experiments where they watched dead sea bass carcasses rot to learn more about how (and why) the soft tissues of internal organs can be selectively preserved in the fossil record.

In the case of dinosaur mummies, there is an ongoing debate about what appears to be a central contradiction. The dino mummies discovered so far show evidence of two different mummification processes. One is fast burial, where the body is quickly covered and advanced decomposition is slowed down considerably and the remains are protected from disposal. The other common path is desiccation, which requires the body to be exposed to the landscape for a certain amount of time before burial.

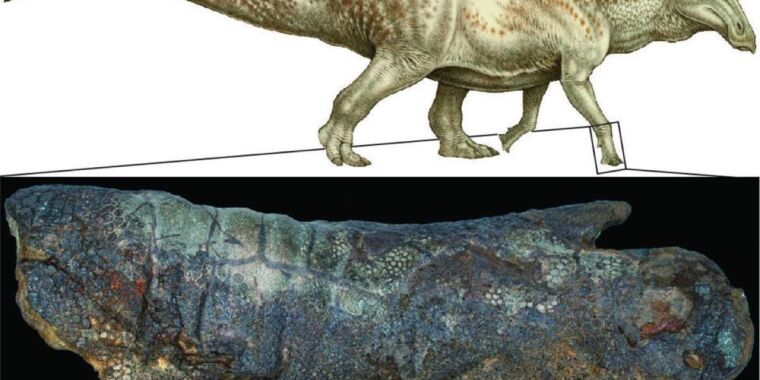

The specimen in question is the partial skeleton of Edmontosaurus, a duck-billed hadrosaur, discovered in the Hell Creek Formation of southwestern North Dakota and is now part of the North Dakota State Fossil Collection. Dubbed “Dakota,” this mummified dinosaur showed signs of both rapid burial and desiccation. The remains have been studied with various tools and techniques since 2008. The authors of the PLoS ONE paper also performed CT scans of the mummy, along with an analysis of the grain size of the surrounding sediments in which the fossil was found.

There was evidence of multiple wounds and punctures in the forelimb and tail, as well as holes and abrasions on the arm, hand bones, and skin in the shape of an arc, much like the shape of crocodile teeth. There were also longer V-shaped cuts on the tail that could have been made by a larger carnivorous predator, such as a juvenile Tyrannosaurus rex.

Becky Barnes/PloS A

The authors concluded that there is probably more than one path to dinosaur mummification, settling the debate in a way that “does not require a spectacularly unlikely coincidence”. In short, dinosaur remains may be mummified more often than previously believed.

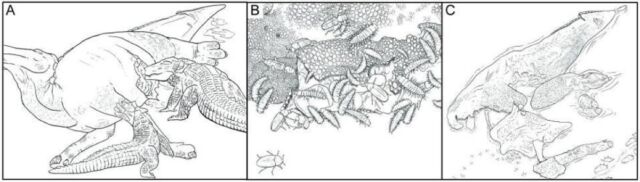

In the case of Dakota, the deflated appearance of the skin over the underlying bones has been observed in other dino mummies and is also well documented in modern forensic studies. The authors believe Dakota was “mummified” through a process called “desiccation and deflation,” which involves incomplete scavenging, emptying animal carcasses as scavengers and decomposers target internal tissues, leaving behind skin and bones. According to David Bressan of Forbes, this is probably what happened to Dakota:

After the animal died, its body was probably scavenged by a bunch of crocodiles, opening the carcass at its belly and colonizing it with flies and beetles, cleaning bones and skin from the rotting flesh. Such an incomplete rinse would have exposed the inside of the skin tissue, after which the outer layers slowly dried out. The underlying bones would prevent the empty hull from shrinking too much, preserving the finer details of the scaly skin. Finally, the now mummified remains were buried under mud, perhaps from a sudden flash flood, and circulating fluids deposited minerals, replacing the remaining soft tissue and preserving an imprint in the rock.

“Not only did Dakota teach us that durable soft tissues, such as skin, can be preserved on partially scavenged carcasses, but these soft tissues can also provide a unique source of information about the other animals that interacted with a carcass after death.” said co-author Clint Boyd, a paleontologist with the North Dakota Geological Survey.

DOI: PLoS ONE, 2022. 10.1371/journal.pone.0275240 (About DOIs).