There’s rarely time to write about every cool science story that comes our way. That’s why we’re posting a special Twelve Days of Christmas series again this year, in which every day from December 25 to January 5 we highlight a scientific story that fell through the cracks in 2022. Today: Scientists attached video cameras to dolphins to capture the sights and sounds of the animals as they hunted prey to learn more about their feeding behavior.

Scientists attached GoPro cameras to six dolphins and captured the sights and sounds of the animals as they hunted and devoured various species of fish — even screaming in victory at the capture of baby sea snakes, according to an August article published in the journal PLoS ONE. While audio and video have previously been recorded of dolphins finding and eating dead fish, the authors say this is the first footage to combine sound and video from the dolphins’ point of view as they chased free-swimming live prey. The audio element allowed the scientists to learn more about how the dolphins communicated while hunting.

Sam Ridgway and his colleagues at the National Marine Foundation in San Diego, California, have previously done research on dolphins. They thought they could learn even more about the animals’ hunting and feeding strategies by using inexpensive commercial GoPro cameras to record both audio and video. The high number of frames per second (60, 90 or 120 FPS) allowed them to observe changes in behavior frame by frame.

The US Navy trains dolphins in captivity to identify mines, among other things. (While the dolphins are technically free to swim away, most “choose” to stay.) Two of those dolphins — identified as S and K — were led by their trainer’s boat into San Diego Bay. There they were given 50 minutes to search for food. Images were captured of 15 such outings for dolphin S and 5 outings for dolphin K. Dolphins B and T wore cameras while swimming in a 6 x 12 meter above ground seawater pool. Live Pacific mackerel, sardines and northern anchovies from a live bait supplier were released into the pool for B and T to hunt. Finally, dolphins Y and Z were filmed incidentally catching prey while swimming freely in the open ocean.

During the course of the study, S caught 69 fish and K caught 40 fish, including spotted sand bass, striped sand bass, smelt, yellowfin tuna, California halibut, and pipefish. The fish were caught both on the surface (particularly smelt) and, more often, on the seabed, lurking in patches of vegetation. The audio revealed that, for example, S would buzz and scream to find the hidden fish in the final scenario, where he swallowed a mouth full of sediment, swallowed the fish, and ejected the sediment and all the plant material back into the water. (One fish managed to escape the dolphin’s jaws and swam away.)

-

Dolphin S with camera on the left side of her harness.

-

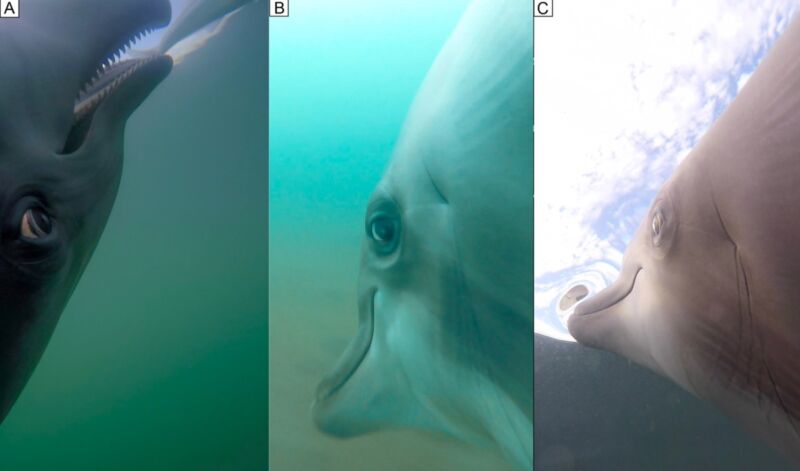

Dolphin S drills into the seabed to grab a fish. Notice the white of the eye or sclera (arrow) that turns the eye toward the fish. C. Dolphin S brings the fish forward with flared lips in the posterior half of the gaping area to show the top row of teeth and the angular area expanding.

-

Dolphin T (a) locates a fish, right eye turned forward. (b) When catching, the lower back lip is pulled down, exposing the gums and teeth and fish (arrow) in the mouth. (c) The dolphin reorients the fish while still pulling the lip down and enlarging the angular area, apparently causing intraoral pressure reduction, but the fish nearly escapes.

-

Order of fish. A. View of a dolphin’s front body while catching fish. B. Relative amplitude of the sound recorded when dolphin S located, chased and caught wild fish. C. Spectrogram of audible sound showing variations in pulse rate and peak frequency characteristic of a squeal.

One of the surprising findings was the ability of all dolphins to open their upper and lower lips to suck prey into their mouths. For example, dolphins B (collected in the 1980s in the Gulf of Mexico) and T caught their fish in the saltwater pool, using a sideways sweep of the head. There were a few examples of so-called “ram-feeding” – in which prey is quickly overtaken and clamped in the jaws before being swallowed – especially when hunting on the surface, but most feeding events mainly used the suction method.

T had been stranded on a Florida beach as a baby in 2013 and raised at Sea World of Florida, so T had never been seen catching live fish before. But after seeing B catch prey, T pounced and started hunting merrily. “His catches were accompanied by a lot of screeching,” the authors wrote.

Dolphins Z and Y were also recorded screaming a victory while catching prey, and Z actually fed on 8 (possibly newborn) yellow-bellied sea snakes – an unusual choice, as dolphins were not previously known to feed on sea snakes ( although they have been observed playing “cat and mouse” with sea serpents). “Perhaps the dolphin’s lack of experience feeding on dolphin groups in the wild led to the consumption of these outlier prey,” the authors wrote. Fortunately, “our dolphin showed no signs of illness after eating the little snakes.”

DOI: PLoS ONE, 2022. 10.1371/journal.pone.0265382 (About DOIs).

Dolphin Z catches sea snakes in the Pacific Ocean with headbutts and a victory cry. Credit: Ridgway et al., 2022