The year 2022 will be remembered across the US for its devastating floods and storms, as well as for its extreme heat waves and droughts.

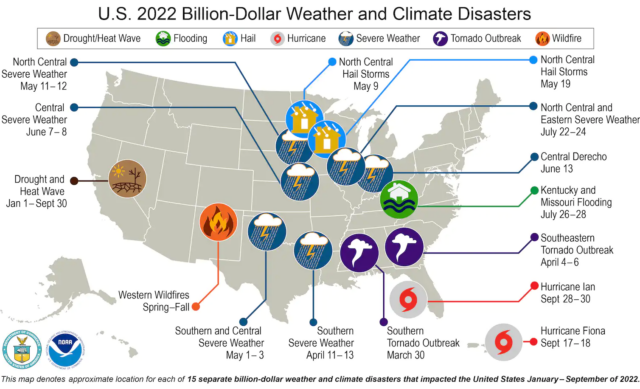

By October, the US had already experienced 15 disasters, each causing more than $1 billion in damage, well above average. The year began and ended with widespread severe winter storms from Texas to Maine, affecting tens of millions of people and causing significant damage. Subsequently, March set the record for the most reported tornadoes in the month – 233.

Over a five-week period in the summer, five 1,000-year rainfall events occurred in St. Louis, eastern Kentucky, southern Illinois, California’s Death Valley, and Dallas, causing devastating and sometimes deadly flash floods. Severe flooding in Mississippi shut down Jackson’s troubled water supply for weeks. A historic flood in Montana, caused by heavy rainfall and melting snow, forced large swathes of Yellowstone National Park to be evacuated.

In the fall, Hurricanes Ian and Fiona flooded Florida and Puerto Rico with more than 20 feet of rain in areas and deadly, destructive storm surges. Ian became one of the costliest hurricanes in US history. And a typhoon pounded 1,000 miles off the Alaskan coast.

While too much rain threatened some regions, extreme heat and too little precipitation exacerbated risks elsewhere.

Persistent heat waves lingered over large parts of the country and set temperature records. Wildfires raged in Arizona and New Mexico against the backdrop of a mega-drought in the US Southwest, more severe than anything the region has experienced in at least 1,200 years.

Drought in the fall also caused the Mississippi River to be so low near Memphis that barges could not get through without additional dredging and upstream water discharges. That snarled grain shipments during the critical harvest period. Along the Colorado River, officials discussed even tighter restrictions on water use as water levels in major reservoirs approach dangerously low levels.

NCEI/NOAA

The United States was hardly alone in its climate disasters.

In Pakistan, record monsoon rains flooded more than a third of the country, killing more than 1,500 people. In India and China, prolonged heat waves and droughts dried up rivers, disrupted power grids and threatened food security for billions of people. Widespread flooding and mudslides caused by torrential rains also killed hundreds in South Africa, Brazil and Nigeria.

In Europe, heatwaves drove record temperatures across Britain and other parts of the continent, leading to severe droughts, low river flows slowing shipping and bushfires in many parts of the continent. Much of East Africa is still in the grip of a multi-year drought — the worst in more than 40 years, according to the United Nations — leaving millions of people vulnerable to food shortages and famine.

This is not just another bizarre year: such extreme events are occurring with increasing frequency and intensity.

Climate change exacerbates these disasters

The most recent global climate assessment from the United Nations Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change found a significant increase in both the frequency and intensity of extreme temperatures and precipitation, leading to more droughts and floods.

Extreme floods and droughts are also becoming more deadly and costly, despite an improving ability to manage climate risks, a study published in 2022 found. Part of the reason is that today’s extreme events, amplified by climate change, are often beyond the management capabilities of communities.

Extreme events are, by definition, rare. A 100-year flood has a 1 percent chance of happening in any given year. So when such events occur with increasing frequency and intensity, they are a clear indication of a changing climate state.

Climate models showed that these risks were coming

Much of this is well understood and consistently reproduced by climate models.

As the climate warms, a shift in the temperature distribution leads to more extremes. For example, globally, a 1° Celsius increase in annual average temperature is associated with a 1.2° C to 1.9° C (2.1° Fahrenheit to 3.4° F) increase in annual maximum temperature.

In addition, global warming is leading to changes in the way the atmosphere and ocean move. The temperature difference between the equator and the poles is the driving force behind the global wind. Since the polar regions warm much faster than the equator, the reduced temperature difference causes a weakening of global winds and leads to a more meandering jet stream.

Some of these changes can create conditions such as persistent high-pressure systems and atmospheric blocking that cause more intense heat waves. The heat domes over the southern plains and south in June and west in September were both examples.

Buckle in the jet stream may explain how it reached 38 °C (100 °F) in Canada while simultaneously dropping significant cold along the west and east coasts of North America.

Very cold in eastern Canada and the northeastern states of the US. Around record cold here for the time of year. pic.twitter.com/6hY25JoTpx

— Scott Duncan (@ScottDuncanWX) June 20, 2022

Warming can be further amplified by positive feedbacks.

For example, higher temperatures tend to dry out the soil, and less soil moisture reduces the heat capacity of the land, making it easier to warm. More frequent and persistent heat waves lead to excess evaporation, combined with decreased precipitation in some regions, leading to more severe droughts and more frequent wildfires.

Ars Technica

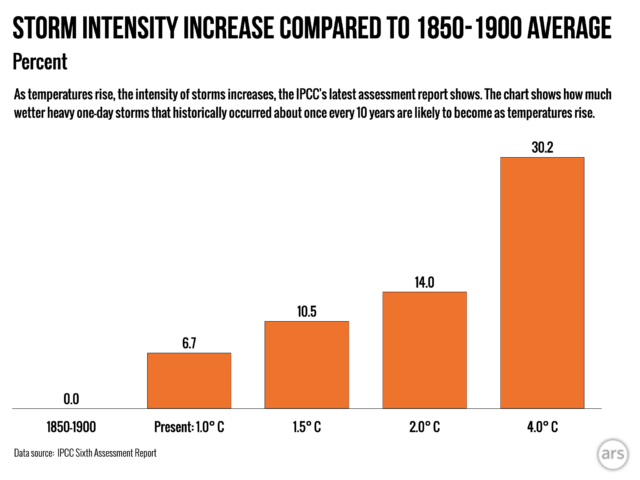

Higher temperatures increase the atmosphere’s ability to hold moisture by about 7 percent per degree Celsius. This increased humidity leads to heavier rainfall.

In addition, storm systems are fueled by latent heat — the large amount of energy released when water vapor condenses into liquid water. Increased moisture in the atmosphere also enhances the latent heat in storm systems, increasing their intensity. Extremely heavy or sustained rainfall leads to increased flooding and landslides, with devastating social and economic consequences.

While it’s hard to directly link specific extreme events to climate change, when these supposedly rare events become more common in a warming world, it’s hard to ignore the changing state of our climate.

The new abnormal

This year may offer a glimpse into our near future as these extreme climate events become more frequent.

To say this is the “new normal” is misleading, however. It suggests that we have reached a new steady state, which is far from the truth. Without serious efforts to curb greenhouse gas emissions, this trend towards more extreme events will continue.

Shuang-Ye Wu is a professor of geology and environmental geosciences at the University of Dayton

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.