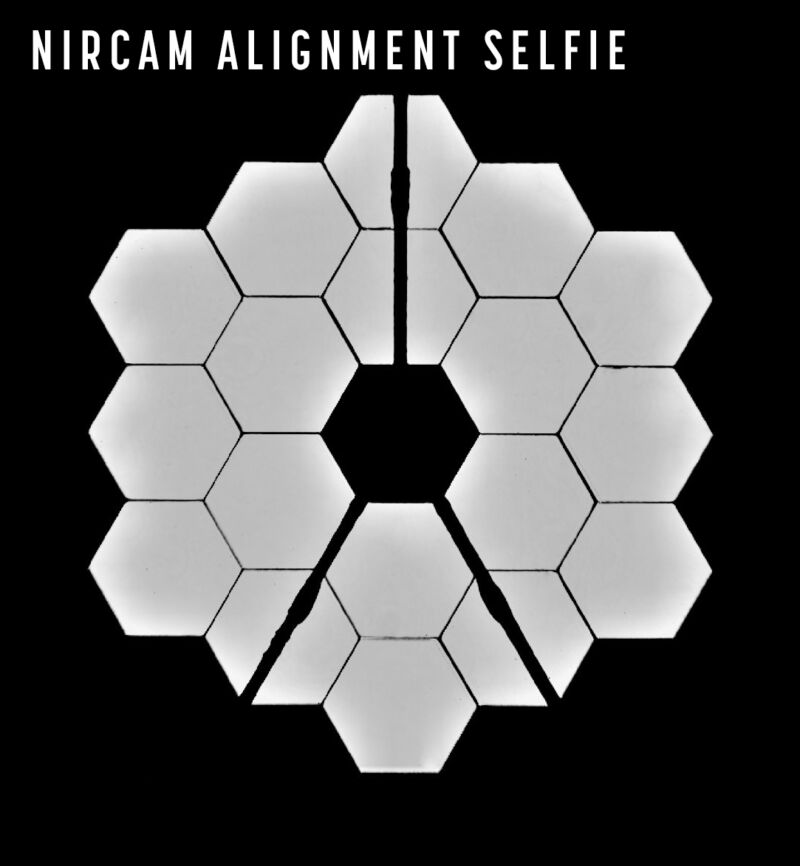

How often does something work exactly as planned and live up to its hype? In most of the world, that’s the equivalent of stumbling across a unicorn holding a few winning lottery tickets between its teeth. But that pretty much describes our main science story of 2022, the successful deployment and the first images from the Webb telescope.

In fact, much good news came from the world of science, with a steady stream of fascinating discoveries and tantalizing potential technology – more than 200 individual papers attracted 100,000 readers or more, and the topics they covered came from all fields of science. Of course, with a pandemic and climate change, not everything we wrote was good news. But as the year’s top stories indicate, our readers found interest in a remarkable range of topics.

For better or worse, Anthony Fauci has become the public face of the US pandemic response. He’s trusted by some for his personal, straightforward advice on managing the risks of infection — and maligned by others for his vaccine advocacy (plus a handful of conspiracy theories). So when Fauci himself ended up on the wrong side of risk management and contracted a SARS-CoV-2 infection, that was news too, and our pandemic specialist, Beth Mole, was there for it.

As it turned out, the trajectory of his infection was a metaphor for the pandemic itself, where every silver lining seems to be delivered with a few extra gray clouds. Fauci took Paxlovid, a drug that was developed thanks to very rapid scientific work discovering the structure of viral proteins and then identifying molecules that could fit into that structure. By design, Paxlovid quickly and effectively suppresses the SARS-CoV-2 infections that cause COVID-19.

Then again, there’s those gray clouds: Once the course of treatment ends, many people experience a resurgence of symptoms for reasons we’re still working out. And Fauci was no exception, with symptoms so severe that he went back on the drug only to stop them again — even though that’s not recommended by the Food and Drug Administration.

Neutron stars are probably the most extreme objects in the universe (black holes are, per se, more of an aberration in spacetime than an object). They are places where the highest “mountains” are less than a millimeter, and cracks in the Earth’s crust can cause violent bursts of radiation. They are also places where the interior is a superfluid of rapidly circulating subatomic particles.

But in a handful of these stars, conditions become even more extreme, as all the charged particles in the superfluid interior can create a dynamo like the one in the Earth’s core that creates our magnetic field. Except just a little stronger. Well, as Paul Sutter describes it, 1016 times stronger. These are the magnetars, a short-lived state of some neutron stars (they last about 10,000 years, which is short for astronomy).

There are plenty of ways a neutron star can kill you, given its intense gravity and tendency to spew out lethal levels of radiation. But magnetars have an extra trick: they do away with chemistry. The magnetic fields are so strong that they can distort the atomic orbitals that control how different atoms attach to each other to form chemical bonds. When you get within 600 miles of a magnetar, that deformation becomes so severe that the chemical bonds no longer function. All of your atoms are left free to roam as they see fit, which is generally not conducive to life.

This article was a personal reflection by Eric Berger, reflecting on the changes in NASA and the launch industry since he began reporting on both about two decades ago. For most of that time, NASA’s budget was dominated by the Space Launch System, which finally made its maiden flight this year, sending hardware to the moon and returning for a flawless landing.

In the wake of that launch, you’d expect the play to focus on that success. Instead, Berger argued that the program’s many failures — countless delays and cost overruns — changed the entire launch industry, giving small companies like SpaceX and Blue Origin a chance to thrive while their established competitors focused on making the most of SLS. to fetch. contracts. Without the problems of SLS, Berger argues, the vehicles that will eventually lead NASA to a successful future of manned exploration may never have been built.