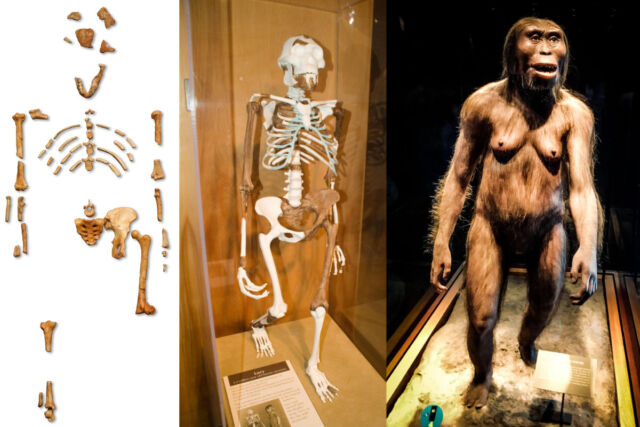

3D reconstruction of the muscles of the lower extremities Australopithecus afarensis fossil AL 288-1, aka “Lucy.” Credit: Ashleigh Wiseman

One of the most famous fossils in human evolutionary history is known as “Lucy”, which belonged to an extinct species called Australopithecus afarensis– an early relative of homo sapiens who was one of the first hominids to walk upright. But scientists have long debated the extent of her bipedality. Now, a 3D digital reconstruction of Lucy’s muscular anatomy, combined with computer simulations, has reaffirmed that she was quite capable of fully upright walking. The results appeared in a new paper published in the journal Royal Society Open Science.

“Lucy’s ability to walk upright can only be determined by reconstructing the path and space a muscle occupies in the body,” said author Ashleigh Wiseman, an archaeologist at the University of Cambridge. “We are now the only animal that can stand upright with straight knees. Lucy’s muscles suggest she was as adept at bipedalism as we are, while she may also have felt at home in the trees.

Lucy’s remains were found in Ethiopia in 1974 at a site called Hadar. Several paleoarchaeologists, including Donald Johanson, Mary Leakey, and Yves Coppens, began examining the site for signs of fossils related to human origins. The first interesting find occurred in November 1971, when Johanson found a petrified upper tibia and, nearby, the lower end of a femur. Now known as AL 129-1 and more than 3 million years old, the angle of the knee joint indicated that this was a hominin (now known as Australopithecus afarensis) be able to walk upright.

But the really important find came on November 24, 1974, when Johanson and fellow expedition member Tom Gray decided to look at the bottom of a small trench. Johanson saw an arm bone fragment, then a skull fragment, then part of a femur. Further research over the next few weeks turned up many more bones, including vertebrae, part of a pelvis, ribs and jaw fragments, all belonging to the same individual hominin. All told, there were several hundred fossilized bone fragments that made up 40 percent of a complete female skeleton. This was ‘Lucy’, aka AL 288-1, named after the 1967 Beatles song ‘Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds’, which had been played loudly and repeatedly on a camp tape recorder.

Once all the parts were put together, scientists were able to reconstruct Lucy, revealing that she was about 4 feet 10 inches tall and weighed about 60 pounds. Her brain was small, like that of a chimpanzee, but her pelvis and leg bones (including a valgus knee) appeared almost identical to modern humans, indicating that Australopithecus afarensis was completely bipedal, i.e. stood upright and walked upright.

How Lucy died is a matter of heated scientific debate. A controversial 2016 paper suggested that careful analysis of her bones reveals how she died — by falling to her death from a very tall tree — though other scientists (including Johanson) thought the evidence was thin at best. As we reported at the time, University of Texas-Austin anthropologist John Kappelman and his team performed a full X-ray CT scan on Lucy’s bones, which allowed them to create high-resolution 3D renderings and 3D prints of her skeleton. to make.

Comparing the way her bones fragmented to contemporary X-rays of people who fell, they concluded that the fragmentation of her leg bone was “green,” that is, it occurred just before she died. In particular, the joint in Lucy’s leg suffered extreme compression of the type one would expect in someone falling onto their feet from a great height, perhaps from a local tree where nests can be as high as 80 feet off the ground. However, skeptics pointed out that the process of fossilization often fragments bones in exactly the way Lucy’s bones are broken, and animals fossilized at the same time as Lucy have similar fractures.