NASA

The launch of the Artemis I mission in mid-November was spectacular, and NASA’s Orion spacecraft has performed almost flawlessly ever since. If all goes as expected — and there’s no reason to believe it won’t — Orion will crash into calm seas off the coast of California this weekend.

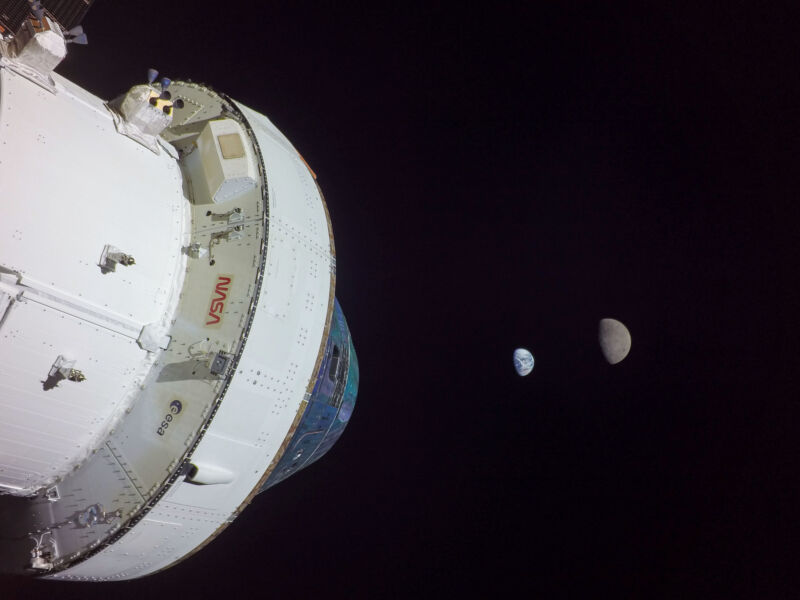

This reconnaissance mission has yielded dazzling photos of the Earth and Moon and promised that humans will soon be flying into deep space again. So the question for NASA is when can we expect an encore?

Realistically, a sequel to Artemis I is probably at least two years away. Most likely, the Artemis II mission won’t take place before early 2025, although NASA isn’t giving up hope of sending humans into space in 2024.

It may seem strange that there is such a long gap. After all, with its flight in November, the Space Launch System rocket has now proven its capabilities. And should Orion return safely to Earth, it will validate the calculations of engineers who designed and built the heat shield. Should it really take more than two years to build a second rocket and spacecraft and complete certification of life support systems in Orion?

The short answer is no, and the reason for the long gap is a bit absurd. It all goes back to a decision made about eight years ago to close a $100 million budget gap in the Orion program. Due to a series of events that followed this decision, Artemis II is unlikely to fly before 2025 due to eight relatively small flight computers.

“I hate to say that this time it’s Orion holding us back,” Mark Kirasich, who was NASA’s program manager for Orion when the decision was made, said in an interview. “But I’m raising in the back. And it’s part of my legacy.”

A long time ago, in a budget far away

About eight years ago, senior officials at NASA and Orion’s prime contractor, Lockheed Martin, had to fill a gap in the budget. At the time, NASA was spending $1.2 billion a year developing the Orion spacecraft, and while it was making progress on the design, there were still challenges.

NASA’s reconnaissance plans at the time were substantially different from today’s Artemis program. Nominally, the agency built Orion and the SLS rocket as part of a “Journey to Mars.” But there was no clear plan to get there and no well-defined missions for Orion to fly.

One key difference is that NASA only intended to fly the original version of the SLS rocket, known as “Block 1”, only once. After this first mission, the agency planned to upgrade the missile’s upper stage, creating a version of the missile known as “Block 1B”. Because this variant was larger and more powerful than Block 1, it required significant modifications to the rocket’s launch tower. NASA engineers estimated that after the initial SLS launch, it would take nearly three years of work to complete and test the reconstructed tower.

NASA

So it seemed plausible that the Orion planners could reuse some components from their spacecraft’s first flight on the second. In particular, they focused on a series of two dozen electronic “boxes” that are part of the electronic system that operates Orion’s communications, navigation, display and flight control systems. They estimated it would take about two years to re-certify the flight hardware.

By not having to build two dozen avionics boxes for Orion’s second flight, the program closed the $100 million budget gap. And in terms of planning, they would have almost a year to spare while the launch tower was being worked on.

“It was just a budget decision,” Kirasich said. “The launch dates were completely different back then.”