Wired | Getty Images

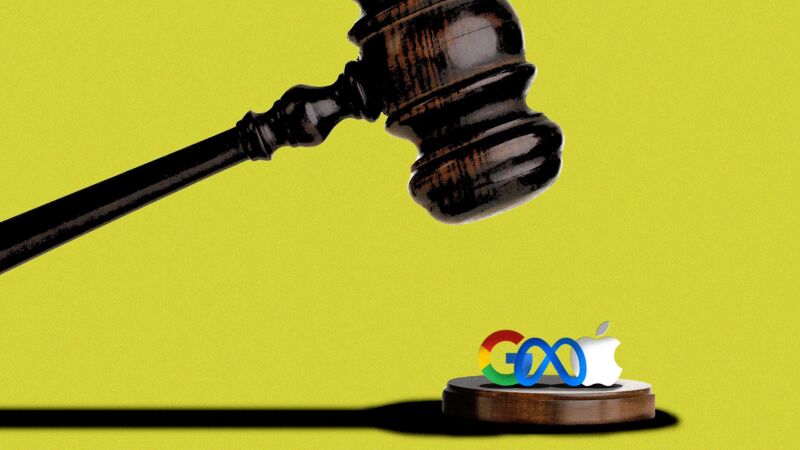

If you want to know how concerned an industry is about a pending legislation, a good measure is how apocalyptic the predictions are about what the bill would do. By that standard, Big Tech is deeply concerned by the US Innovation and Choice Online Act.

The unhappily named law aims to prevent dominant online platforms – such as Apple and Facebook and especially Google and Amazon – from giving themselves an advantage over other companies that have to go through it to reach customers. Since one of the committee’s two antitrust bills was passed by a strong bipartisan vote (the other would regulate app stores), it may be this Congress’ best, if not only, chance to stop the biggest tech companies from misusing their money. gatekeeper status.

“It’s the ball game,” said Luther Lowe, senior vice president of policy at Yelp and a longtime Google antagonist. “That way, these guys stay big and relevant. If they can’t get their hands on the scales, they’re vulnerable to small and medium-sized businesses eating up their market share.”

But according to the tech giants and their lobbyists and front groups, the bill, introduced by Amy Klobuchar and Chuck Grassley, the top Democrat and Republican respectively on the Senate Judiciary Committee, would be a disaster for American consumers. In an ongoing publicity campaign, they’ve claimed it would ruin Google’s search results, ban Apple from offering useful features on iPhones, force Facebook to stop moderating content, and even ban Amazon Prime. It’s all pretty alarming. Is anything true?

The central idea of the legislation is that a company operating a marketplace should not be able to set special rules for itself within that marketplace because competitors who object do not have a realistic place to go. No business can afford to be left out of Google’s search index, and few online retailers can make a living without being listed on Amazon. So the Klobuchar-Grassley Act broadly prohibits self-preference by platforms that reach certain thresholds, such as monthly active users or annual revenue. To give a simple example, it would mean that Amazon can’t give its own branded products an edge over other brands when someone shops on its site, and Google can’t choose to give YouTube links when someone does a video search unless they do. the left are objectively most relevant.

Furthermore, it’s hard to say exactly what the law would do, as it leaves quite a bit unspecified. Like many federal statutes, it mandates an administrative agency—in this case, the Federal Trade Commission—to translate broad provisions into concrete rules. And it gives the FTC, the Department of Justice and prosecutors the power to sue companies for violating those rules. (Last week, the DOJ approved the bill, an important signal of support from the Biden administration.) Inevitably, both the rules and any enforcement actions will eventually be litigated in court, leaving federal judges ultimately in control of what makes law. exactly means.

This leaves a lot of uncertainty about exactly how the law would turn out. In that zone of uncertainty, the tech companies have issued dire warnings.

Perhaps the most terrifying point of contention is that the law, if passed, would kill Amazon Prime. According to eMarketer, more than 150 million Americans, more than half of the adult population, are Prime members. That’s a lot of people who hate to lose their “free” two-day shipping. (Of course, it’s not really free if you have to pay a subscription fee.)