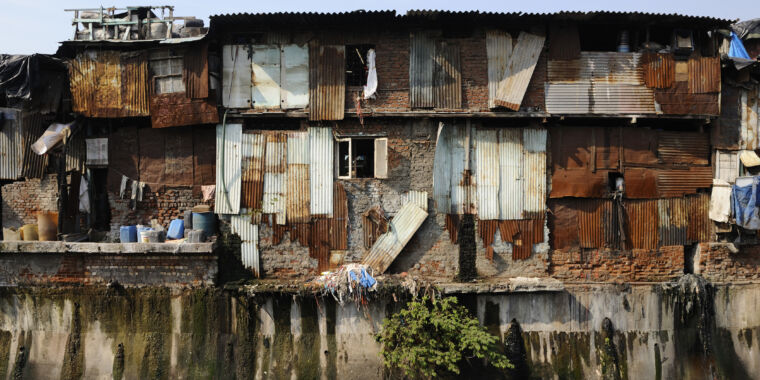

The United Nations’ first Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) aims to eradicate poverty around the world. If implemented, however, it could result in people consuming more – driving more often, buying more products – and thus producing more carbon emissions, fueling climate change. “With more money to spend, and therefore more consumption, there is usually a larger ecological footprint,” Benedikt Bruckner, a master’s student in energy and environmental sciences at the University of Groningen, told Ars.

But that doesn’t necessarily have to be the case, according to a new study by Bruckner, other researchers from Groningen and colleagues in the United States and China.

The research, published in Nature, uses high-level data on consumption patterns to show that achieving SDG 1 – putting everyone out of extreme poverty (less than $1.90 a day) and half of everyone above the poverty line of their respective countries – will not exaggerate climate change.

‘A nice data set’

The paper aims to answer a pressing question: “What are the carbon cost implications of poverty reduction?” Klaus Hubacek, another author of the paper and a professor of science, technology and society at the U of G, told Ars. In 2017, Hubacek and his colleagues conducted a similar study looking at the trade-off between carbon emissions and poverty reduction. For this work, they used a large World Bank dataset with consumption data broken down into four income categories: lowest, low, medium and high.

For this new study, the team used a revised World Bank dataset (to which they contributed) that distinguishes between 201 different spending categories in 116 different countries, representing a total of 90 percent of the population. But the team was unable to use all the data in the set and there were some gaps. Japan, for example, has no information at the individual level, only at the household level. Still, “It’s a much finer figure, a nice data set,” Hubacek said.

The team used this data to get a very detailed picture of the carbon footprint of consumption for people in each group and country. The dataset also includes information on poverty levels within each country. The team then looked at emissions data from those already above the poverty line to determine the effects of lifting more people out of poverty. All in all, they found that lifting more than a billion people out of poverty worldwide would increase global carbon emissions by just 1.6 to 2.1 percent.

Must be the money

This is still an increase in emissions. But a bigger problem is that many of the richest people in the world consume more and thus cause more emissions. Hubacek noted that the paper doesn’t explicitly look at the difference between the amounts of carbon produced by the wealthy compared to those living in poverty.

In a press release, however, Bruckner noted that the richest 1 percent of the world produced 50 percent more emissions than those in the poorest 50 percent. For example, Hubacek noted that the average European produces about six tons of carbon per year, while most people living in poverty emit less than one ton.

As such, the world meeting its climate goals would not be hampered by efforts to lift people out of poverty. But some of the richest countries and people around the world need to start consuming less. “Poverty reduction is really not a big problem, and it will not lead us to higher CO2 emissions worldwide,” Bruckner said.

Nature, 2022. DOI: 10.1038/s41893-021-00842-z (About DOIs)