The Large Magellanic Cloud, the largest satellite galaxy in the Milky Way. Accurate estimates of the distance to this galaxy help calibrate measurements of the universe’s expansion rate.

If a person is lost in the wilderness, they have two options. They can look for civilization, or they can make themselves easily recognizable by lighting a fire or writing HELP in big letters. For scientists interested in whether intelligent aliens exist, the options are much the same.

For more than 70 years, astronomers have been scanning for radio or optical signals from other civilizations in the search for extraterrestrial intelligence called SETI. Most scientists are convinced that life exists on many of the 300 million potentially habitable worlds in the Milky Way Galaxy. Astronomers also think there’s a decent chance that some life forms have evolved intelligence and technology. But no signs of another civilization have ever been discovered, a mystery called “The Great Silence.”

While SETI has long been part of mainstream science, METI, or extraterrestrial intelligence messaging, is less common.

I am an astronomy professor who has written extensively about the search for life in the universe. I’m also on the advisory board of a nonprofit research organization that designs messages to send to alien civilizations.

In the coming months, two teams of astronomers will send messages into space in an effort to communicate with intelligent aliens who can listen out there.

These efforts are like building a big bonfire in the woods and hoping someone finds you. But some people wonder if it’s wise to do this at all.

The history of METI

Early attempts to contact life beyond Earth were quixotic messages in a bottle.

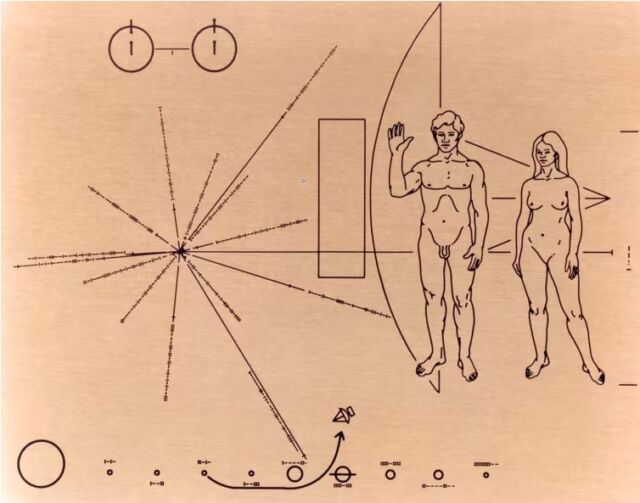

In 1972, NASA launched the Pioneer 10 spacecraft toward Jupiter with a plaque depicting a line drawing of a man and a woman and symbols to indicate where the craft came from. In 1977, NASA followed this up with the famous gold record attached to the Voyager 1 spacecraft.

These spacecraft — as well as their twins, Pioneer 11 and Voyager 2 — have all now left the solar system. But in the immensity of space, the chances of finding these or other physical objects are fantastically miniscule.

Electromagnetic radiation is a much more effective beacon.

Astronomers beamed out the first radio message designed for alien ears from the Arecibo Observatory in Puerto Rico in 1974. Designed to convey simple information about humanity and biology, the string of ones and zeros was sent to the globular cluster M13. . Since M13 is 25,000 light-years away, don’t hold your breath for an answer.

In addition to these deliberate attempts to send a message to aliens, idiosyncratic signals from television and radio broadcasts have been leaking into space for nearly a century. This ever-expanding bubble of earthly chatter has already reached millions of stars. But there’s a big difference between a focused explosion of radio waves from a giant telescope and diffuse leakage – the weak signal of a show like I love Lucy fades under the hum of radiation left over from the Big Bang, shortly after it leaves the solar system.