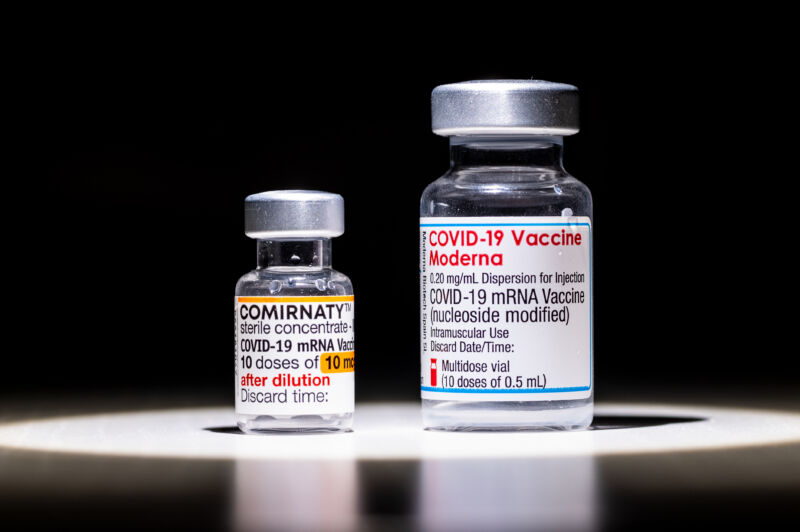

The mRNA-based COVID-19 vaccines, made by Pfizer/BioNTech and Moderna, have proven highly effective in preparing our immune systems to fight off the pandemic coronavirus – preventing significant amounts of infection, serious illness and death in several waves of variants . But despite their similar design and efficacy, the two vaccines aren’t exactly the same — and our immune systems don’t respond to them in the same way.

An early hint of this was some real-world data showing surprising differences in the effectiveness of the two vaccines, despite both injections performing nearly identically in Phase III clinical trials — 95 percent and 94 percent. Amid last year’s delta wave, a Mayo Clinic study found that Pfizer’s effectiveness against infection dropped to 42 percent, while Moderna’s only fell to 76 percent.

Such differences may be explained by evidence that the two vaccines prompt the immune system to produce slightly different antibodies against SARS-CoV-2, according to a new study in Science Translational Medicine.

Both vaccines generate strong levels of neutralizing antibodies, which can bind to the virus and prevent it from infecting cells. But according to the study, the vaccines generated different antibody profiles in general. Notably, the antibody response to the Pfizer/BioNTech vaccine shifted to a class of antibodies called IgG and IgM, which are commonly found in the blood. The Moderna vaccine, meanwhile, generated relatively elevated levels of IgA antibodies, a class of antibodies generally found on mucosal surfaces, such as the respiratory tract, where SARS-CoV-2 infections begin. In addition, the Moderna vaccine produced relatively higher levels of antibodies that activate immune cells called natural killer cells. It also generated higher levels of antibodies that activate immune cells called neutrophils to take in and kill (phagocytose) invading germs.

Detailed differences

The study, led by Harvard immunologist and virologist Galit Alter, identified the differences by comparing the antibody profiles of 28 people vaccinated with the Moderna vaccine and 45 people vaccinated with the Pfizer/BioNTech vaccine. The numbers were small and the participants were mostly healthy young female medical workers, which is not representative of the general population. The study also didn’t look at immune responses over time. Instead, the researchers looked at antibody profiles about a month after each participant received a second vaccine dose.

But “despite these limitations, these data provide evidence for possible nuanced differences in the quality of the humoral immune response elicited by SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccines,” Alter and her colleagues wrote. While both vaccines generally produce a strong immune response, these small differences in antibody “may provide insight into possible differences in protective immunity conferred by these vaccines,” they concluded.

Alter and her colleagues will need to conduct more research to determine whether these differences are related to differences in protection and vaccine effectiveness. And they will also need to do more research to understand what exactly causes the differences. The Pfizer/BioNTech and Moderna vaccines are not only made with different formulations of components, they are also given at different doses and with different time intervals between doses. Moderna’s vaccine is given as two 100 microgram doses four weeks apart, while the Pfizer/BioNTech vaccine is given as two 30 microgram doses three weeks apart.

Those factors can change how the immune system responds to the vaccines. But by digging into those differences, researchers can create “tunable” mRNA vaccines that generate specific antibody responses to provide the strongest protection. In the meantime, the findings make the case for people to mix and match mRNA vaccine boosters, especially if they’ve started taking doses of the Pfizer/BioNTech vaccine. Switching to a different vaccine for a future booster may diversify the antibody response and provide broader protection.