Researchers have unearthed a discovery not common in the malware field: a mature, never-before-seen Linux backdoor that uses new evasion techniques to hide its presence on infected servers, in some cases even involving a forensic investigation.

On Thursday, researchers from Intezer and The BlackBerry Threat Research & Intelligence Team said the previously undetected backdoor combines high levels of access with the ability to remove any sign of infection from the file system, system processes and network traffic. Called Symbiote, it targets financial institutions in Brazil and was first discovered in November.

Researchers for Intezer and BlackBerry wrote:

What makes Symbiote different from other Linux malware we commonly encounter is that it has to infect other running processes in order to harm infected machines. Rather than being a standalone executable that runs to infect a machine, it’s a shared object (SO) library that is loaded into all running processes with LD_PRELOAD (T1574.006), and parasitic the machine infects. Once it has infected all running processes, it provides the threat actor with rootkit functionality, the ability to collect credentials, and remote access.

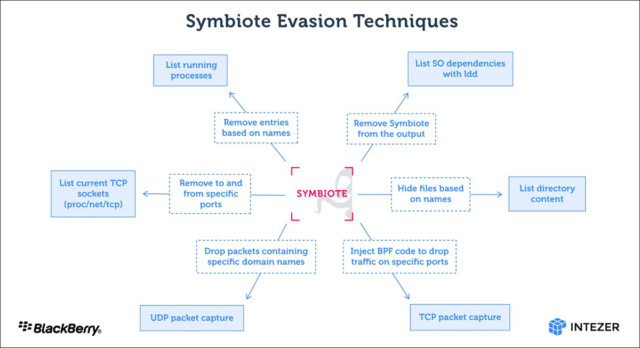

Using LD_PRELOAD, Symbiote loads before all other shared objects. This allows the malware to tamper with other library files loaded for an application. The image below shows a summary of all the malware’s evasion techniques.

BPF in the image refers to the Berkeley Packet Filter, which allows people to hide malicious network traffic on an infected machine.

“When an administrator launches a packet capture tool on the infected machine, it injects BPF bytecode into the kernel that determines which packets to capture,” the researchers wrote. “In this process, Symbiote adds its bytecode first so it can filter network traffic that it doesn’t want the packet capture software to see.”

One of the stealth techniques that Symbiote uses is known as libc function hooking. But the malware also uses hooking in its role as a data theft tool. “Reference collection is performed by linking the libc read function,” the researchers wrote. “When an ssh or scp process calls the function, it captures the credentials.”

So far there is no evidence of infection in the wild, only malware samples found online. This malware is unlikely to be widely active at this point, but how can we be sure with this robust stealth?