Trevor Mahlmann

On Friday afternoon, senior NASA officials took part in a conference call to speak with reporters about the current plan to launch the Artemis I mission from Kennedy Space Center in Florida. This will be the third attempt to get the massive Space Launch System rocket off the ground and launch the Orion spacecraft into orbit around the moon for an unmanned test flight of about 40 days before returning to Earth.

The missile is ready, officials said. During tank tests and launch attempts, NASA has been besieged by hydrogen propellant leaks, as the small molecule is difficult to handle and contain in super-cold temperatures. However, after a longer-than-expected but ultimately successful propellant charging test on Wednesday, NASA engineers expressed confidence in their revamped fueling procedures.

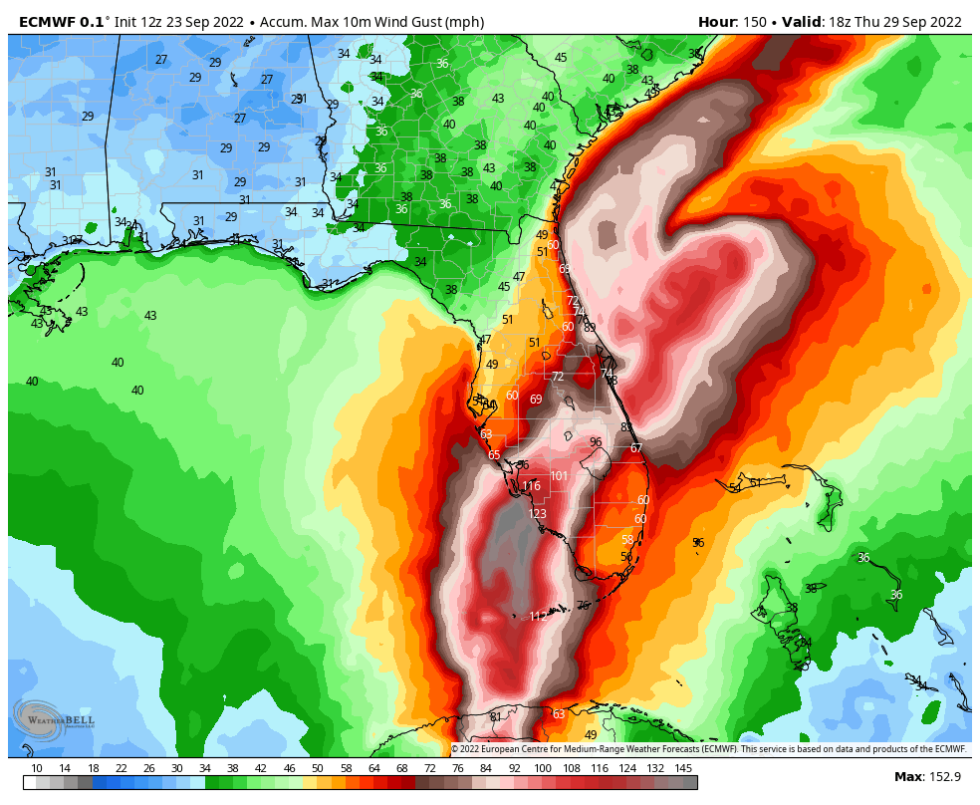

NASA has also reached an agreement with US Space Force officials to extend the battery life for the onboard system for terminating the flight of the rocket. This left only the weather as a potential constraint for a scheduled launch attempt for Tuesday, September 27 at 11:37 a.m. EST (15:37 UTC). The problem is, the weather now poses a significant threat to the schedule due to a tropical depression likely to head toward Florida in the coming days. There is an 80 percent chance of unacceptable weather during the launch window.

To roll or not to roll

Despite the bleak forecast, NASA is pushing ahead.

“Our Plan A is to stay on track and launch the 27th,” said Mike Bolger, the manager of NASA’s Exploration Ground Systems Program at Kennedy Space Center. “We also realize that we really need to pay attention and think about a plan B.”

Bolger explained that NASA’s backup plan involved rolling the rocket and spacecraft back into the large Vehicle Assembly Building, a few miles from the launch pad, where it would be protected from the elements. Preparing the rocket and rolling it back would take about three days, he said. NASA hopes to wait a day, until Saturday, to make a final decision. NASA officials will meet again Friday night to discuss the weather.

These comments were reasonable and it is prudent for NASA to ensure it has the best available data on Tropical Depression Nine, which has only recently developed a center of circulation. As a result, forecasts should improve over the next two days.

This is a delicate balance for NASA: waiting long enough to get the best forecast, but also allowing enough time to turn the rocket back and let employees out of the space center before the worst storm arrives. According to the National Hurricane Center on Friday afternoon, the earliest “reasonable arrival time” for tropical storm winds is around noon Tuesday, so waiting until Saturday morning would close.

Off the rails

However, after Bolger’s comments, the teleconference began to derail somewhat. It became clear that NASA officials were not just waiting for forecast data, but were hesitant to roll the SLS rocket back to its hangar. SLS chief engineer John Blevins said he wouldn’t be inclined to roll the rocket back to its hangar, even if the space center were hit by a tropical storm, which has less wind than a hurricane, but still a hefty one. blows.

“If we really did experience a real hurricane, my recommendation would be that we consider rolling back,” Blevins said. “Normally the footprint of those things isn’t that wide, you know, for those high winds.”

Based on NASA’s risk assessments, Blevins said he believed the SLS rocket and Orion spacecraft could withstand winds of up to 74.1 knots (85 mph) at a height of 60 feet above the ground. The primary risk is wind loading on the vehicle, but he acknowledged there would be concerns about “things that could move in such a storm.” This is a somewhat curious risk stance from a space agency that is obsessively concerned about “foreign object waste” with its space hardware.

Weather Bello

So what’s the benefit of risking the rocket and spacecraft, which were developed at more than $30 billion, in a tropical system? By waiting for the weather, NASA is trying to preserve a chance to launch on September 27 or October 2. If that doesn’t work, it has to go back to the hangar anyway.

This would likely make the next launch attempt in the second half of November. “In that case, some life-limited items would emerge,” Blevins said. This seemed to be an admission that for NASA, the clock is ticking on a rocket that has now been fully stacked for launch for nearly a year and has critical parts that cannot be serviced in that configuration. In short, NASA officials would really like to get off the trail as soon as possible.