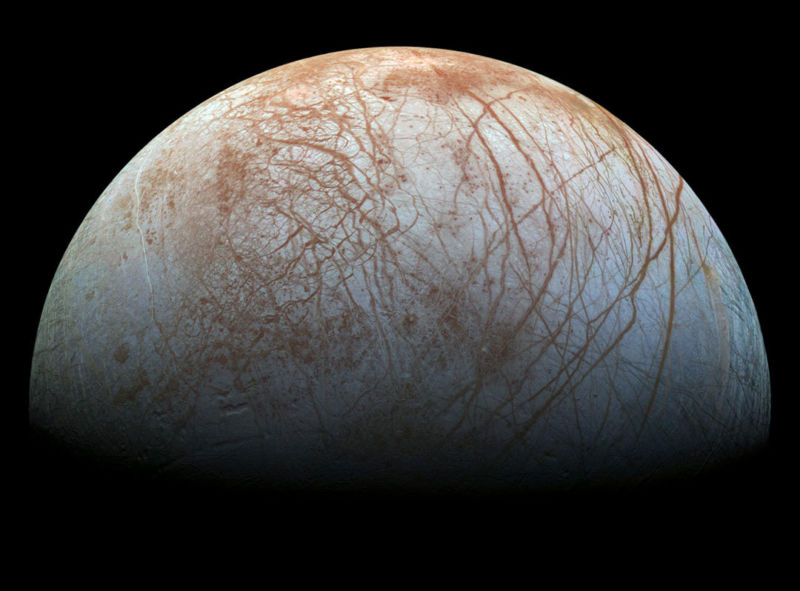

On Thursday morning, NASA’s Juno spacecraft dove down to 358 km from the surface of Europa, the large ice-covered moon orbiting Jupiter.

This flyby will provide mankind with the best view of Europe since the Galileo mission made several close flybys more than two decades ago. However, the Juno spacecraft will carry a more powerful array of instruments and a much more capable camera than Galileo. So this should be our best look into the intriguing world yet.

Launched in 2011, Juno reached Jupiter in 2016 to closely study the composition of the solar system’s largest planet, as well as its powerful magnetosphere. After successfully completing its primary mission in 2021, Juno’s mission operators have begun using the probe to assess moons in the Jupiter system, including Europa, Ganymede and Io.

Given Juno’s existing orbit and Jupiter’s massive gravitational field, the orbital dynamics of the Europa flyby are challenging to say the least, and Juno had to make significant changes to its orbit.

“The relative speed between spacecraft and moon will be 23.6 kilometers per second, so we’re screaming by pretty fast,” said John Bordi, Juno’s deputy mission manager at JPL. “All steps must go like clockwork to successfully obtain our planned data, because shortly after the flyby is completed, the spacecraft must be reoriented for our approaching approach to Jupiter, which is only seven and a half hours later.”

Scientists have long been curious about Europa, which is covered in ice but believed to have a huge ocean below its surface due to the moon’s warm core. There is probably more liquid water in Europe’s global ocean than there is on Earth, planetary scientists think. Although the ice sheet is believed to be several kilometers thick, the Hubble Space Telescope has collected data indicating that geysers may periodically eject through cracks in this ice. Given the presence of water and heat, this ocean is considered a potential reservoir for microbial extraterrestrial life.

Juno will bring new instruments to study this ice sheet. For example, the spacecraft’s microwave radiometer will look into the crust of Europa and obtain data on its icy composition and temperature. This is the first time such data has been collected to study the moon’s icy shell.

The visual images and science data will help inform NASA scientists who are completing the assembly of the Europa Clipper, a large spacecraft that will launch on a Falcon Heavy rocket in 2024. This mission will be devoted to the study of the moon, which will arrive in 2030 and will conduct more than 50 flybys at close range to collect data. Ultimately, the space agency wants to send a lander, but first wants to get data from the flyby missions to assess the best location for landing, possibly near a water vapor plume, if they actually exist.

In the coming days, images should return from Juno’s flyby of Europe. NASA will post them here as soon as they arrive.