Perhaps counterintuitively, sediment layers on the seafloor are more likely to remain intact than on land, so they can provide a better picture of the region's history. The seafloor is a more stable, low-oxygen environment, which resists erosion and dissolution (two reasons why scientists find many more fossils of marine animals than land dwellers) and preserves finer details.

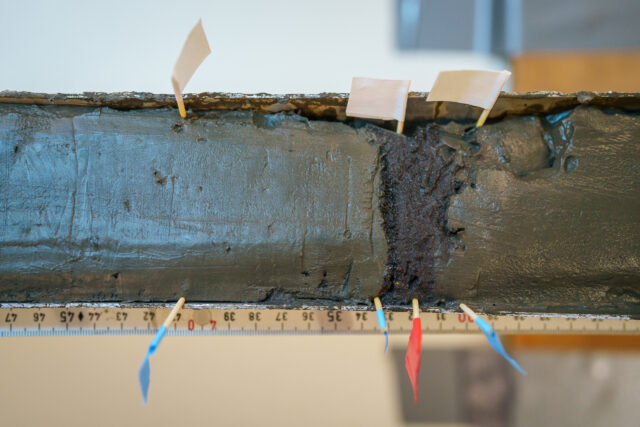

A close-up of a core sample taken by a vibracorer. Scientists mark places they want to inspect more closely with flags.

Credit: Alex Ingle / Schmidt Ocean Institute

Samples from different areas vary greatly in time coverage; for some they go back only as far as 2008 and for others possibly more than 15,000 years due to vastly different sedimentation rates. Scientists will use techniques such as radiocarbon dating to determine the age of sediment layers in the core samples.

ROV SuBastian saw a helmeted jellyfish during the expedition. These photophobic (light-avoiding) creatures glow via bioluminescence.

Credit: Schmidt Ocean Institute

Microscopic analysis of the sediment cores will also help the team analyze how the eruption affected marine life and seafloor chemistry.

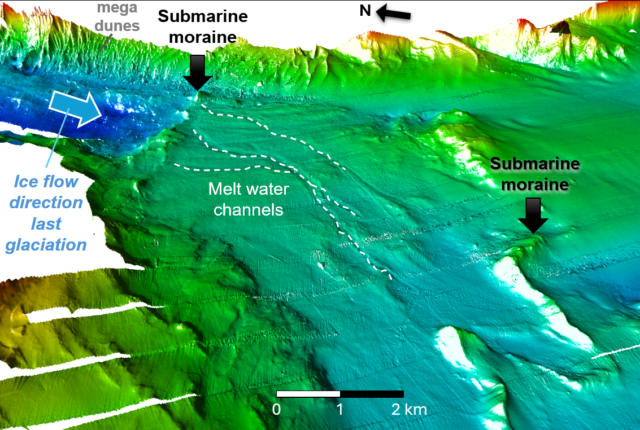

“A wide variety of life and sediment species were found at the different sites we investigated,” said Alastair Hodgetts, a physical volcanologist and geologist at the University of Edinburgh, who took part in the expedition. “The oldest site we visited – an area scarred by ancient glacial movements – is a fossilized seascape that was completely unexpected.”

In an area beyond the dunes, ocean currents have kept the seabed free of sediment. This preserves the seabed features left by the retreat of the ice sheets at the end of the last ice age.

Credit: Rodrigo Fernández / CODEX Project

This characteristic also tells scientists about the way the water moves. Currents flowing over an area long ago eroded by a glacier sweep away sediment, leaving the old terrain exposed.

“I am very interested in analyzing seismic data and correlating them with the layers of sediment in the core samples to create a timeline of geological events in the area,” says Giulia Matilde Ferrante, a geophysicist at the Italian National Institute for Oceanography and Applied Geophysics. , who co-led the expedition. “By reconstructing the past in this way, we can better understand the sediment history and landscape changes in the region.”

In this post-apocalyptic scene captured on June 20, 2008, a thick layer of ash covers the city of Chaitén as the volcano continues to erupt in the background. About 5,000 people were evacuated and resettlement efforts did not begin until the following year.

Credit: Javier Rubilar

The team has already collected measurements of the amount of sediment the eruption delivered into the sea. Now they will try to determine whether older layers of sediment record previous, unknown events similar to the 2008 eruption.

“A better understanding of past volcanic events, by revealing things like how far away an eruption reached, and how frequent, severe and predictable eruptions are, will help plan future events and reduce the impact they have on local communities,” said Watt.

By day, Ashley writes about space for a contractor for NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center and works freelance as an environmental writer. She has a master's degree in space studies from the University of North Dakota and scientific writing from Johns Hopkins University. She writes most of her articles with a baby on her lap.